Code of the United States Fighting Force

The Code of the U.S. Fighting Force is a code of conduct that is an ethics guide and a United States Department of Defense directive consisting of six articles to members of the United States Armed Forces, addressing how they should act in combat when they must evade capture, resist while a prisoner or escape from the enemy. It is considered an important part of U.S. military doctrine and tradition, but is not formal military law in the manner of the Uniform Code of Military Justice or public international law, such as the Geneva Conventions.

History

[edit]The early history of rules for the army was founded by Abraham Lincoln who signed the Lieber Code in 1863.

This section may require cleanup to meet Wikipedia's quality standards. The specific problem is: Written in an inappropriate narrative and editorializing style, rather than Wikipedia's encyclopaedic style. (April 2018) |

During the Korean War in the early 1950s, Chinese and North Korean forces captured American military personnel as prisoners of war. Unlike America's previous wars, these American prisoners faced a harsher POW environment. It was the first American war that U.S. prisoners of war were viewed by an enemy as more than soldiers from the other side temporarily restrained from conducting war. The POW camps sought to control the minds of U.S. prisoners. North Korean and Chinese communists were not hesitant to use brutal and bloody torture as gruesome tools in their efforts to exploit U.S. prisoners of war into making public statements that appeared favorable to the communist war effort. For the American prisoners, brutal torture, lack of food, absence of medical aid, and subhuman treatment became a daily way of life and many of them found that their training had not prepared them for this new battlefield.[1][2]

Although collaborating with the enemy was not new, its ramifications caused considerable damage to the morale and survival of U.S. POWs during the Korean War and later the Vietnam War. Before the Korean War, American prisoners in previous wars were subjected to inhumane and brutal treatment but the enemy did not take it upon itself to tear down the chain of command within the prisoner ranks. When the communists succeeded in breaking this hierarchy, an atmosphere of distrust among the prisoners became the norm rather than the exception. Morale dropped and mutual assistance among the prisoners lessened. The failure of the POWs to care for their fellow prisoners resulted in a higher death rate and made the captives more amenable to accept the doctrine of their captors.[1][2]

One of the most elaborate propaganda efforts was the 1952 POW Olympics held in Pyuktong, North Korea. For 12 days in November, approximately 500 prison athletes from Britain, South Korea, Australia, Turkey, and the U.S. competed against other camps in events mirroring the World Olympics such as baseball, boxing, and track and field. This effort was publicized to show the world just how well the UN prisoners were treated. Of course, this was not the reality. Very few American servicemen were mentally prepared to protect themselves from such barbaric treatment and intense indoctrination attempts. Through inhumane treatment and manipulation, many prisoners were forced to collaborate with the communists.[1][2]

After the termination of the hostilities in Korea and the subsequent release of American prisoners of war, twenty-one Americans chose to remain in China, refusing repatriation. Many former U.S. prisoners coming back to their homeland were criminally charged and tried for offenses that "amounted to treason, desertion to the enemy, mistreatment of fellow prisoners of war, and similar crimes." The emotions and compassion of the public were aroused, as graphic details of the inhumane treatment of U.S. POWs in communist prison camps surfaced during the trials. Public discussion caused intense arguments over what should have been done about Americans who were "brainwashed" in Korea and what to do about those in future wars who may be the recipients of similar bloody treatment.[1][2]

On August 7, 1954, the United States Secretary of Defense directed that a committee be formed to recommend a suitable approach for conducting a comprehensive study of the problems related to the entire Korean War POW experience. The work of that committee resulted in the May 17, 1955 appointment of the Defense Advisory Committee on Prisoners of War, headed by Carter L. Burgess, assistant secretary of defense for Manpower and Personnel. The committee took heed of the ongoing divisive debate, noting that while all services had regulations governing the conduct of prisoners of war, "the United States armed forces have never had a clearly defined code of conduct applicable to American prisoners after capture."[1][2]

Colonel Franklin Brooke Nihart, USMC, worked at Marine Corps headquarters throughout the summer of 1955, outlined his ideas in longhand and the Code of Conduct was established with the issuance of Executive Order 10631 by President Dwight D. Eisenhower on 17 August 1955 which stated, "Every member of the Armed Forces of the United States are expected to measure up to the standards embodied in the Code of Conduct while in combat or in captivity." It has been modified twice—once in 1977 by President Jimmy Carter in Executive Order 12017, and most recently in President Ronald Reagan's Executive Order 12633 of March 1988, which amended the code to make it gender-neutral.

Notably, the code prohibits surrender except when "all reasonable means of resistance [are] exhausted and...certain death the only alternative," enjoins captured Americans to "resist by all means available" and "make every effort to escape and aid others," and bars the acceptance of parole or special favors from enemy forces. The code also outlines proper conduct for American prisoners of war, reaffirms that under the Geneva Conventions prisoners of war should give "name, rank, service number, and date of birth" and requires that under interrogation captured military personnel should "evade answering further questions to the utmost of [their] ability."

The Army and Marine Corps issued "clear explanations and guidance for the 429 articles of the Geneva Conventions" in 2020.[3][4]

Executive Order 10631: Code of Conduct for members of the Armed Forces of the United States

[edit]The authority for establishing the Code of Conduct, communication of intent, and assignment of responsibilities are outlined in the first three paragraphs of Executive Order 10631.

By virtue of the authority vested in me as President of the United States, and as Commander in Chief of the armed forces of the United States, I hereby prescribe the Code of Conduct for Members of the Armed Forces of the United States which is attached to this order and hereby made a part thereof.

All members of the Armed Forces of the United States are expected to measure up to the standards embodied in this Code of Conduct while in combat or in captivity. To ensure achievement of these standards, members of the armed forces liable to capture shall be provided with specific training and instruction designed to better equip them to counter and withstand all enemy efforts against them, and shall be fully instructed as to the behavior and obligations expected of them during combat or captivity.

The Secretary of Defense (and the Secretary of Transportation with respect to the Coast Guard except when it is serving as part of the Navy) shall take such action as is deemed necessary to implement this order and to disseminate and make the said Code known to all members of the armed forces of the United States.[5]

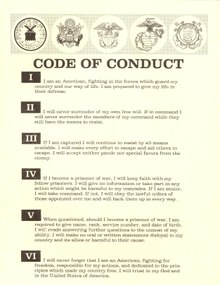

Articles of Code of Conduct

[edit]The Code of Conduct provides guidance for the behavior and actions of members of the Armed Forces of the United States. This guidance applies not only on the battlefield, but also in the event that the service member is captured and becomes a prisoner of war (POW). The Code is delineated in six articles.

Article I:

I am an American, fighting in the forces which guard my country and our way of life. I am prepared to give my life in their defense.[5]

Article II:

I will never surrender of my own free will. If in command, I will never surrender the members of my command while they still have the means to resist.[5]

Article III:

If I am captured I will continue to resist by all means available. I will make every effort to escape and aid others to escape. I will accept neither parole nor special favors from the enemy.[5]

Article IV:

If I become a prisoner of war, I will keep faith with my fellow prisoners. I will give no information or take part in any action which might be harmful to my comrades. If I am senior, I will take command. If not, I will obey the lawful orders of those appointed over me and will back them up in every way.[5]

Article V:

When questioned, should I become a prisoner of war, I am required to give name, rank, service number and date of birth. I will evade answering further questions to the utmost of my ability. I will make no oral or written statements disloyal to my country and its allies or harmful to their cause.[5]

Article VI:

I will never forget that I am an American, fighting for freedom, responsible for my actions, and dedicated to the principles which made my country free. I will trust in my God and in the United States of America.[5]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e "The military Code of Conduct: a brief history". Archived from the original on 16 March 2013. Retrieved 21 July 2015.

- ^ a b c d e "Code of Conduct". Retrieved 17 September 2014.

- ^ Joseph Lacdan (22 January 2020) Army updates Law of Land Warfare doctrine to increase guidance, clarity

- ^ US Army FM 6-27, C1 (20 September 2019) The Commander's Handbook on the Law of Land warfare 208 page handbook. The Department of Defense Law of War Manual (June 2015, updated December 2016) remains the authoritative statement

- ^ a b c d e f g "Executive Order 10631" National Archives. Retrieved 19 October 2016