Bull Durham

| Bull Durham | |

|---|---|

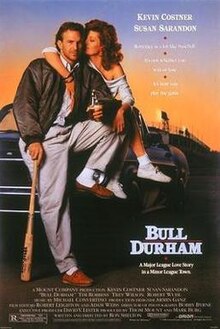

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Ron Shelton |

| Written by | Ron Shelton |

| Produced by | Thom Mount Mark Burg |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Bobby Byrne |

| Edited by | Robert Leighton Adam Weiss |

| Music by | Michael Convertino |

| Distributed by | Orion Pictures |

Release date |

|

Running time | 108 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $9 million |

| Box office | $50.9 million[1] |

Bull Durham is a 1988 American romantic comedy sports film. It is partly based upon the minor-league baseball experiences of writer/director Ron Shelton and depicts the players and fans of the Durham Bulls, a minor-league baseball team in Durham, North Carolina.

The film stars Kevin Costner as "Crash" Davis, a veteran catcher from the AAA Richmond Braves, brought in to teach rookie pitcher Ebby Calvin "Nuke" LaLoosh (Tim Robbins) about the game in preparation for reaching the major leagues. Baseball groupie Annie Savoy (Susan Sarandon) romances Nuke but finds herself increasingly attracted to Crash. Also featured are Robert Wuhl and Trey Wilson, as well as "The Clown Prince of Baseball", Max Patkin.

Bull Durham was a commercial success, grossing over $50 million in North America, well above its estimated budget, and was a critical success as well. Sports Illustrated ranked it the #1 Greatest Sports Movie of all time. The Moving Arts Film Journal ranked it #3 on its list of the 25 Greatest Sports Movies of All-Time. In addition, the film is ranked #55 on Bravo's "100 Funniest Movies." It is also ranked #97 on the American Film Institute's "100 Years...100 Laughs" list, and #1 on Rotten Tomatoes' list of the 53 best-reviewed sports movies.

Plot

[edit]The Durham Bulls, a single-A Minor League Baseball team, are dealing with another sparsely attended losing season, with one thing working for them: Ebby Calvin LaLoosh, a hotshot rookie pitcher known for having a "million dollar arm, but a five cent head," who has potential to become a major league talent. "Crash" Davis, a 12-year veteran in the minor leagues, is sent down from Triple-A as the team's catcher to teach LaLoosh to control his haphazard pitching. Crash immediately begins calling Ebby by the degrading nickname of "Meat", and they get off to a rocky start.

Thrown into the mix is Annie, a "baseball groupie" and lifelong spiritual seeker who has latched onto the "Church of Baseball" and has, every year, chosen one player on the Bulls to be her lover and student. Annie flirts with both Crash and Ebby and invites them to her house, but Crash walks out, saying he's too much of a veteran to "try out" for anything. But before he leaves, Crash sparks Annie's interest with a memorable speech listing the things he "believes in", ending with, "I believe in long, slow, deep, soft, wet kisses that last three days... Good night".

Despite some animosity between them, Annie and Crash work, in their own ways, to shape Ebby into a big-league pitcher. Annie plays mild bondage games, reads poetry to him, gets him to try different mental approaches to pitching, and gives him the nickname "Nuke".

Crash forces Nuke to learn "not to think" by letting the catcher make the pitching calls. After Nuke shakes off his signs, he twice tells the batters what pitch is coming, leading to both players hitting home runs; he also lectures him about the pressure of facing major league hitters who can hit his "heat" (fastballs). Crash talks about life in the major leagues, which he lived for "the 21 greatest days of my life" and to which he has tried for years to return. Meanwhile, as Nuke matures, the relationship between Annie and Crash grows, until it becomes obvious that the two of them are a more appropriate match.

After a rough start, Nuke becomes a dominant pitcher by mid-season, adding to the Bulls' good fortunes; in the end, he is called up to the major leagues. This incites jealous anger in Crash, who is frustrated by Nuke's failure to value the rare talent he has. Nuke leaves, Annie ends their relationship, and Crash overcomes his jealousy enough to leave Nuke with some final words of advice.

The Bulls, now having no use for Nuke's mentor, call up a younger catcher and release Crash. Crash presents himself at Annie's house and the two consummate their attraction with a weekend-long lovemaking session. Crash then leaves Annie's house to seek a further minor-league position.

Nuke is seen one last time, being interviewed by the press as a major leaguer, reciting the clichéd answers that Crash had taught him earlier. Crash joins another team, the Asheville Tourists, and breaks the minor-league record for career home runs. He then retires as a player and returns to Durham, where Annie tells him she's ready to give up her annual affairs with "boys." Crash tells her that he is thinking about becoming a manager for a minor-league team in Visalia. The film ends with Annie and Crash dancing in Annie's candle-lit living room.

Cast

[edit]- Kevin Costner as Lawrence "Crash" Davis

- Susan Sarandon as Annie Savoy

- Tim Robbins as Ebby Calvin "Nuke" Laloosh

- Trey Wilson as Joe "Skip" Riggins

- Robert Wuhl as Larry Hockett

- William O'Leary as Jimmy

- David Neidorf as Bobby

- Jenny Robertson as Millie

- Danny Gans as Deke

- Max Patkin as himself

Background

[edit]The film's name is based on the nickname for Durham, North Carolina, since 1874, when W. T. Blackwell and Company named its product "Bull" Durham tobacco, which soon became a well-known trademark. In 1898, James B. Duke purchased the company and renamed it the American Tobacco Company. By this time, the nickname "Bull City" had already stuck.

The film's writer and director, Ron Shelton, played minor league baseball for five years after graduating from Westmont College in Santa Barbara, California. Initially playing second base for the Baltimore Orioles' farm system, he moved from the Appalachian League to California and then Texas before finally playing AAA baseball for the Rochester Red Wings in the International League. Shelton quit when he realized he would never become a major league player. "I was 25. In baseball, you feel 60 if you're not in the big leagues. I didn't want to become a Crash Davis", he said.[2]

He returned to school and earned a Master of Fine Arts in sculpture at the University of Arizona before moving to Los Angeles to join the city's art scene. However, he felt more kinship in telling stories than in creating performance art. His break into filmmaking came with scriptwriting credits on the films Under Fire and The Best of Times.[2]

According to Justin Turner, the bull in right field that was hit for a home run in the film is actually in left field at Durham Bulls Athletic Park.[3]

Production

[edit]According to Shelton, "I wrote a very early script about minor league baseball; the only thing it had in common with Bull Durham was that it was about a pitcher and a catcher."[4] That script was titled The Player To Be Named Later; a single anecdote from that script made it into Bull Durham.[2] For Bull Durham, Shelton "decided to see if a woman could tell the story" and "dictated that opening monologue on a little micro-recorder while I was driving around North Carolina."[4] Crash was named after Lawrence "Crash" Davis but was modeled after Pike Bishop, the lead character William Holden played in The Wild Bunch: a guy who "loved something more than it loved him."[4] Annie Savoy's name was a combination of the nickname ("Annies") that baseball players gave their groupies and the name of a bar; she was a "High Priestess [who] could lead us into a man's world, and shine a light on it. And she would be very sensual, and sexual, yet she'd live by her own rigorous moral code. It seemed like a character we hadn't seen before."[4] After Shelton returned to Los Angeles from his road trip, he wrote the script for Bull Durham in "about twelve weeks."[4]

Filming began on October 5, 1987, and wrapped on November 30, 1987, after 56 days of filming. When Shelton pitched Bull Durham, he had a hard time convincing a studio to give him the opportunity to direct.[2] Baseball movies were not considered a viable commercial prospect at the time and every studio passed except for Orion Pictures who gave him a $9 million budget (with many cast members accepting lower-than-usual salaries because of the material), an eight-week shooting schedule, and creative freedom.[2] Shelton scouted locations throughout the southern United States before settling on Durham in North Carolina because of its old ballpark and its location, "among abandoned tobacco warehouses and on the edge of an abandoned downtown and in the middle of a residential neighborhood where people could walk".[5] According to NO BULL: The Real Story of the Rebirth of a Team and a City by Ron Morris, Shelton decided because the city was "run down with vacated tobacco warehouses and boarded up downtown storefronts" it made a "down-and-out, minor-league town that represented his story well."[6] The Imperial Tobacco Warehouse, which is currently owned and has been renovated by Measurement Incorporated, was used as a filming location.[7] The Queen Anne style James Manning House, built in 1880, was used for Annie Savoy's romantic encounters.[6]

Shelton cast Costner because of the actor's natural athleticism. Costner was a former high school baseball player and was able to hit two home runs while the cameras were rolling and, according to Shelton, insisted "on throwing runners out even when they (the cameras) weren't rolling".[8] He cast Robbins over the strong objections of the studio, who wanted Anthony Michael Hall instead.[9] Shelton had to threaten to quit before the studio backed off.[4]

Producer Thom Mount (who is part-owner of the real Durham Bulls) hired Pete Bock, a former semi-pro baseball player, as a consultant on the film. Bock recruited more than a dozen minor-league players, ran a tryout camp to recruit an additional 40 to 50 players from lesser ranks, hired several minor-league umpires, and conducted two-a-day workouts and practice games with Tim Robbins pitching and Kevin Costner catching.[2] Bock made sure the actors looked and acted like ballplayers and that the real players acted convincingly in front of the cameras. He said, "The director would say, 'This is the shot we want. What we need is the left fielder throwing a one-hopper to the plate. Then we need a good collision at the plate.' I would select the players I know could do the job, and then we would go out and get it done."[10]

Reception

[edit]Box office

[edit]Bull Durham debuted on June 15, 1988, and grossed $5 million in 1,238 theaters on its opening weekend. It went on to gross a total of $50.8 million in North America, well above its estimated $9 million budget.[1]

Critical response

[edit]"A few months after it came out, I was having dinner at a restaurant called The Imperial Gardens. A man came up and asked if I was Ron Shelton. I said yes, and he said, 'Somebody would like to meet you.' So I followed him—I didn't realize at the time it was Stanley Donen, the director—and he brought me over to his best friend, Billy Wilder. Wilder looked up and said, 'Great fuckin' picture, kid!' I said, 'Mr. Wilder, that's the best review I've ever had!'"

—Director Ron Shelton, in a 2008 interview[4]

The film was well-received critically. On Rotten Tomatoes, the film has an approval rating of 97%, based on 72 reviews, with an average rating of 8.00/10. The website's critical consensus reads, "Kevin Costner is at his funniest and most charismatic in Bull Durham, a film that's as wise about relationships as it is about minor league baseball."[11] On Metacritic, the film has a weighted average score of 73 out of 100, based on 16 critics, indicating "generally favorable reviews".[12] Audiences polled by CinemaScore gave the film an average grade of "B+" on an A+ to F scale.[13]

According to a Los Angeles Times poll of 100 film critics, Bull Durham was the second most acclaimed film of 1988, second to only to the documentary The Thin Blue Line.[14]

In David Ansen's review for Newsweek, he wrote that the film "works equally as a love story, a baseball fable and a comedy, while ignoring the clichés of each genre".[2] Vincent Canby praised Shelton's direction in his review for The New York Times: "He demonstrates the sort of expert comic timing and control that allow him to get in and out of situations so quickly that they're over before one has time to question them. Part of the fun in watching Bull Durham is in the awareness that a clearly seen vision is being realized. This is one first-rate debut".[15]

Roger Ebert praised Sarandon's performance in his review for the Chicago Sun-Times: "I don't know who else they could have hired to play Annie Savoy, the Sarandon character who pledges her heart and her body to one player a season, but I doubt if the character would have worked without Sarandon's wonderful performance".[16] In his review for Sports Illustrated, Steve Wulf wrote, "It's a good movie and a damn good baseball movie".[17] Hal Hinson, in his review for The Washington Post, wrote, "The people associated with Bull Durham know the game ... and the firsthand experience shows in their easy command of the ballplayer's vernacular, in their feel for what goes through a batter's head when he digs in at the plate and in their knowledge of the secret ceremonies that take place on the mound".[18] Richard Corliss, in his review for Time, wrote, "Costner's surly sexiness finally pays off here; abrading against Sarandon's earth-mama geniality and Robbins' rube egocentricity, Costner strikes sparks".[19]

Legacy

[edit]Bull Durham was named Best Screenplay of 1988 by New York Film Critics' Circle.[20] The film became a minor hit when released, and is now considered one of the best sports movies of all time.[21] In 2003, Sports Illustrated ranked Bull Durham as the "Greatest Sports Movie".[22] In addition, the film is ranked number 55 on Bravo's "100 Funniest Movies."[23] It is also ranked #97 on the American Film Institute's "100 Years...100 Laughs" list, and #1 on Rotten Tomatoes' Top Sports Movies[24] list of the 53 best reviewed sports movies of all time. Entertainment Weekly ranked Bull Durham as the fifth best DVD of their Top 30 Sports Movies on DVD.[25] The magazine also ranked the film as the fifth best sports film since 1983 in their "Sports 25: The Best Thrill-of-Victory, Agony-of-Defeat Films Since 1983" poll[26] and #5 on their "50 Sexiest Movies Ever" poll.[27] In June 2008, AFI revealed its "Ten top Ten"—the best ten films in ten "classic" American film genres—after polling over 1,500 people from the creative community. Bull Durham was acknowledged as the fifth best film in the sports genre.[28][29][30] The real life Durham Bulls, playing in the single-A Carolina League at the time of the film's release, would later see the team open a new ballpark (Durham Bulls Athletic Park) in 1995, and would be promoted to the triple-A International League in 1998.

In 2003, a 15th anniversary celebration of Bull Durham at the National Baseball Hall of Fame was canceled by Hall of Fame president Dale Petroskey. Petroskey, who was on the White House staff during the Reagan administration, told Robbins that the actor's public opposition to the US-led war in Iraq helped to "undermine the U.S. position, which could put our troops in even more danger."[31] Costner, a self-described libertarian, defended Robbins and Sarandon, saying, "I think Tim and Susan's courage is the type of courage that makes our democracy work. Pulling back this invite is against the whole principle about what we fight for and profess to be about."[31]

For years, Ron Shelton has contemplated making a sequel and remarked, "I couldn't figure out in the few years right after it came out, what do you do? Nuke's in the big leagues, Crash is managing in Visalia. Is Annie going to go to Visalia? I've been to Visalia. That will test a relationship ... It was not a simple fable to continue with – not that we don't talk about continuing it, now that everyone's in their 60s".[5]

Actor Trey Wilson, who played Durham manager Joe Riggins, died of a cerebral hemorrhage at age 40, seven months after this film's release.

Awards and honors

[edit]- Best Original Screenplay – Ron Shelton (nominated)

- Best Actress – Musical or Comedy – Susan Sarandon (nominated)

- Best Original Song – "When a Woman Loves a Man" (nominated)

Writers Guild of America Award

- Best Original Screenplay – Ron Shelton (won)

Boston Society of Film Critics

- Best Film – (won)

- Best Screenplay – Ron Shelton (won)

Los Angeles Film Critics Association

- Best Screenplay- Ron Shelton (won)

National Society of Film Critics

- Best Screenplay – Ron Shelton (won)

- Best Supporting Actor – Tim Robbins (3rd Place)

1988 New York Film Critics Circle Awards

- Best Screenplay – Ron Shelton (won)

- Best Supporting Actor – Tim Robbins (4th Place)

Other honors

[edit]In 2000, the American Film Institute placed the film on its 100 Years...100 Laughs list, where it was ranked #97.[32] And in 2008, AFI included Bull Durham on its Top 10 Sports Films list as the #5 sports film.[33]

Home media

[edit]Bull Durham was originally released on DVD on October 27, 1998, and included an audio commentary by writer/director Ron Shelton.[34] A Special Edition DVD was released on April 2, 2002, and included the Shelton commentary track from the previous edition, a new commentary by Kevin Costner and Tim Robbins, a Between the Lines: The Making of Bull Durham featurette, a Sports Wrap featurette, and a Costner profile.[35] A "Collector's Edition" DVD celebrating the film's 20th anniversary was released on March 18, 2008, and features the two commentaries from the previous edition, a Greatest Show on Dirt featurette, a Diamonds in the Rough featurette that explores minor league baseball, The Making of Bull Durham featurette, and Costner profile from the previous edition. The Criterion Collection also released blu-ray and DVD editions of the film which included a new conversation between Shelton and film critic Michael Sragow.[36]

See also

[edit]- List of baseball films

- Fayetteville Generals/Cape Fear Crocs/Lakewood BlueClaws franchise

- Carolina League

- Buzz Arlett (then all-time U.S. minor league home run king when this film was released, whose home run record was broken by Mike Hessman in 2015)

- Major League

- Odd Man Out: A Year on the Mound with a Minor League Misfit

References

[edit]- ^ a b "Bull Durham (1988)". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on August 12, 2019. Retrieved June 2, 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g Ansen, David (June 20, 1988). "A Major-League Romp". Newsweek.

- ^ The LA Dodgers Break Down Baseball Movies | GQ Sports. Retrieved October 22, 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Ron Shelton: From the Red Wings to Bull Durham". December 12, 2008. Archived from the original on July 10, 2011. Retrieved July 13, 2009.

- ^ a b "Shelton celebrates 20 years for Bull Durham". Southern Ledger. May 1, 2008. Archived from the original on May 3, 2008. Retrieved May 5, 2008.

- ^ a b Allam, Chantal (May 17, 2024). "For $1.6M, 'Bull Durham' house hits market selling Southern charm and 1980s nostalgia". News and Observer.

- ^ "THE IMPERIAL TOBACCO COMPANY | Open Durham". www.opendurham.org. Archived from the original on June 17, 2019. Retrieved July 7, 2018.

- ^ Bierly, Mandi (November 18, 2005). "MVP: Kevin Costner". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on June 1, 2007. Retrieved January 17, 2008.

- ^ Hall was cast as a high school quarterback in another Orion film—Johnny Be Good—released three months before Bull Durham.

- ^ Van Gelder, Lawrence (June 10, 1988). "At the Movies". The New York Times. Archived from the original on July 28, 2018. Retrieved September 25, 2007.

- ^ "Bull Durham (1988)". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango Media. Archived from the original on March 24, 2020. Retrieved April 1, 2020.

- ^ "Bill Durham Reviews". Metacritic. CBS Interactive. Archived from the original on April 26, 2018. Retrieved April 10, 2018.

- ^ "BULL DURHAM (1988) B+". CinemaScore. Archived from the original on February 6, 2018. Retrieved October 14, 2018.

- ^ McGilligan, Pat; Rowland, Mark (January 8, 1989). "100 Film Critics Can't Be Wrong, Can They? : The critics' consensus choice for the 'best' movie of '88 is . . . a documentary!". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on March 8, 2021. Retrieved August 8, 2020.

- ^ Canby, Vincent (July 3, 1988). "Toons and Bushers Fly High". The New York Times. Archived from the original on July 28, 2018. Retrieved September 25, 2007.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (June 15, 1988). "Bull Durham". Chicago Sun-Times. Archived from the original on March 2, 2021. Retrieved January 1, 2021.

- ^ Wulf, Steve (July 4, 1988). "Bull Durham". Sports Illustrated. Archived from the original on May 11, 2008. Retrieved April 24, 2008.

- ^ Hinson, Hal (June 15, 1988). "Bull Durham". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on December 11, 2017. Retrieved January 8, 2021.

- ^ Corliss, Richard (June 20, 1988). "I Sing the Body Athletic". Time. Archived from the original on April 24, 2015. Retrieved January 1, 2021.

- ^ Maslin, Janet (December 16, 1988). "Accidental Tourist Wins Film Critics' Circle Award". The New York Times. Archived from the original on November 23, 2018. Retrieved March 31, 2010.

- ^ Ballew, Bill. "Bull Durham Adds Another Chapter to McCormick Field History". The Asheville Tourists. Archived from the original on January 23, 2007. Retrieved April 9, 2007.

- ^ "The Greatest Sports Movies". Sports Illustrated. August 4, 2003. Archived from the original on May 17, 2008. Retrieved April 24, 2008.

- ^ "Bravo's 100 Funniest Films". Boston.com. July 25, 2006. Archived from the original on October 18, 2007. Retrieved September 25, 2007.

- ^ "Top Sports Movies". Rotten Tomatoes. 2007. Archived from the original on September 23, 2007. Retrieved 2007-09-25.

- ^ Bernardo, Melissa Rose (November 11, 2005). "Jock Stars". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on June 7, 2011. Retrieved January 17, 2008.

- ^ "The Sports 25: The Best Thrill-of-Victory, Agony-of-Defeat Films Since 1983". Entertainment Weekly. September 22, 2008. Archived from the original on September 1, 2008. Retrieved September 22, 2008.

- ^ "50 Sexiest Movies Ever". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on February 3, 2009. Retrieved January 22, 2009.

- ^ American Film Institute (June 17, 2008). "AFI Crowns Top 10 Films in 10 Classic Genres". ComingSoon.net. Archived from the original on June 19, 2008. Retrieved June 18, 2008.

- ^ "Top 10 Sports". American Film Institute. Archived from the original on August 10, 2013. Retrieved June 18, 2008.

- ^ "'Bull Durham': Ranking the 37 best quotes from the classic baseball movie". www.sportingnews.com. April 18, 2019. Archived from the original on July 19, 2020. Retrieved July 18, 2020.

- ^ a b "Tim Robbins: Hall of Fame violates freedom". The Age. Melbourne. April 13, 2003. Archived from the original on October 27, 2017. Retrieved November 1, 2020.

- ^ "AFI's 100 Years...100 Laughs" (PDF). American Film Institute. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 16, 2013. Retrieved August 28, 2016.

- ^ "AFI's 10 Top 10: Top 10 Sports". American Film Institute. Archived from the original on May 24, 2013. Retrieved August 28, 2016.

- ^ Hunt, Bill (November 7, 1998). "Bull Durham". Digital Bits. Archived from the original on November 20, 2007. Retrieved January 17, 2008.

- ^ Bovberg, Jason (March 17, 2002). "Bull Durham: SE". DVD Talk. Retrieved January 17, 2008.

- ^ Woodward, Tom (January 17, 2008). "Bull Durham". DVD Active. Archived from the original on December 5, 2008. Retrieved January 17, 2008.

External links

[edit]- 1988 films

- 1988 romantic comedy films

- 1980s sports films

- 1980s sports comedy films

- American baseball films

- American romantic comedy films

- 1988 directorial debut films

- Durham Bulls

- Films directed by Ron Shelton

- Films scored by Michael Convertino

- Films set in North Carolina

- Films shot in Durham, North Carolina

- Orion Pictures films

- American sports comedy films

- 1980s English-language films

- 1980s American films

- English-language romantic comedy films

- English-language sports comedy films