Astor Place

40°43′47″N 73°59′29″W / 40.729861°N 73.991434°W

Astor Place is a street in NoHo/East Village, in the lower part of the New York City borough of Manhattan. It is divided into two sections: One segment runs from Broadway in the west (just below East 8th Street) to Lafayette Street, and the other runs from Fourth to Third Avenues. The street encompasses two plazas at the intersection with Cooper Square, Lafayette Street, Fourth Avenue, and Eighth Street – Alamo Plaza and Astor Place Station Plaza. "Astor Place" is also sometimes used for the neighborhood around the street.[1] It was named for John Jacob Astor (at one time the richest person in the United States), soon after his death in 1848.[2] A $21 million reconstruction to implement a redesign of Astor Place[3] began in 2013 and was completed in 2016.[4]

Geography

[edit]The American Guide Series describes the Astor Place district as running from Houston Street north to 14th Street, between Broadway and Third Avenue.[5] The Encyclopedia of New York City defines the neighborhood as between 4th Street and 8th Street, from Broadway to Third Avenue.[1]

History

[edit]Astor Place was originally a powwow point for the various Lenape tribes of Manhattan and was called Kintecoying or, "Crossroads of Three Nations".[6]

Astor Place was once known as Art Street. From 1767 through 1859, Vauxhall Gardens, a country resort, was located on this street.[7] The area belonged to John Jacob Astor, and Astor Place was renamed after him soon after his death, in 1848.[2] In 1826, he carved out an upper-class neighborhood from the site with Lafayette Street bisecting eastern gardens from western homes. Wealthy New Yorkers, including Astor and other members of the family, built mansions along this central thoroughfare. Astor built the Astor Library in the eastern portion of the neighborhood as a donation to the city. Architect Seth Geer designed row houses called LaGrange Terrace for the development, and the area became a fashionable, upper-class residential district.[8] This location made the gardens accessible to the people of both the Broadway and Bowery districts.[9]

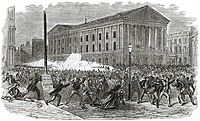

Astor Place was the site of the Astor Opera House, at the intersection of Astor Place, East 8th Street, and Lafayette Street. Built to be the fashionable theater in 1847, it was the site of the Astor Place Riot of May 10, 1849. Anti-British feelings were running so high among New York's Irish at the height of the Great Famine that they found an outlet in the rivalry between American actor Edwin Forrest and the English William Charles Macready, who were both presenting versions of Macbeth in nearby theatres. The protest in the streets against Macready became so violent that the police fired into the crowd. At least 18 died, and hundreds were injured. The theater itself never recovered from the association with the riot and was closed down shortly afterwards. The interior was demolished, and the building was turned over to the use of the New York Mercantile Library.

From 1852 until 1936, Astor Place was the location of Bible House, headquarters of the American Bible Society.[10]

In the mid- to late-19th century, the area was home to many of the wealthiest New Yorkers, including members of the Astor, Vanderbilt, and Delano families. Editor and poet William Cullen Bryant, and inventor and entrepreneur Isaac Singer lived in the neighborhood in the 1880s.[11] By the turn of the century, however, warehouses and manufacturing firms moved in, the elite moved to places such as Murray Hill, and the area fell into disrepair. The neighborhood was revitalized beginning in the late 1960s and 1970s.[1]

The New York City Department of Transportation's "Reconstruction of Astor Place and Cooper Square" plan[3] called for some changes to be made to Astor Place beginning in 2013. The street would end at Lafayette Street rather than continuing east to Third Avenue. This allowed the expansion of the "Alamo Plaza", where the Alamo Cube is located, south to the southern sidewalk of Astor Place between Lafayette Street and Cooper Square, and the creation of an expanded sidewalk north of the Cooper Union Foundation Building. The Astor Place subway entrance plaza was also redesigned, and Fourth Avenue south of East 9th Street and the western part of Cooper Square was converted to be used by buses only, with a new pedestrian plaza created on Cooper Square between East 5th and 6th Streets. The traffic pattern of the area changed significantly, with Astor Place from Lafayette Street to Third Avenue becoming East Eighth Street eastbound, and the formerly bidirectional Cooper Square bus lane becoming northbound-only.[3] The $16 million project[12] was first proposed in 2008, then abandoned and re-proposed in 2011. Construction started in September 2013,[13] and the work was completed in November 2016.[4][14]

Points of interest

[edit]

The current 299-seat Off-Broadway Astor Place Theatre, has been located in the landmark Colonnade Row on Lafayette Street, half a block south, since 1969. It was known for premiering works by downtown playwrights like Sam Shepard, but since 1991 has been the home of Blue Man Group, which now owns the theatre. The Joseph Papp Public Theater (home to the New York Shakespeare Festival) is located across the street in the former Astor Library building.

The trapezium-shaped traffic island in the center of Astor Place is a popular meeting place and center of much skateboarding activity. The island is most notably home to Tony Rosenthal's sculpture "Alamo", known popularly as "The Cube", which consists of a large, black metal cube mounted on one corner. Installed in 1967 as part of the "Sculpture and the Environment" organized by the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs, the Alamo Cube has since become a popular meeting place in the East Village.[15][16][17][18] The sculpture can be spun on its vertical axis by one person with some effort, and two or more people without trouble. In 2003, the cube was the subject of a prank played by the ATF squad (All Too Flat) in which it was turned into a giant Rubik's Cube. The members of the organization were careful with the prank, as they didn't want to be destructive. The cube stayed up for about 24 hours before city maintenance removed the painted cardboard panels from the sculpture. On March 10, 2005, the Parks Department removed the Cube for maintenance. The original artist and crew replaced a missing bolt, and made a few other minor repairs. A makeshift replica of PVC tubes named the Jello Cube in honor of Peter Cooper was placed in its stead. As of November 2005, the Cube returned with a fresh coat of black paint, still able to spin.[15]

Other nearby points of interest include:

- In 1860, Abraham Lincoln came to the attention of the fledgling Republican party with his Cooper Union Address. Given in The Cooper Union's Great Hall, the 'Right Makes Might' speech examined federal control of slavery and the thoughts of the signers of the Constitution. Cooper Union also housed one of the first free public libraries.

- One of the original libraries making up the New York Public Library, the Astor Library was housed in the Astor Library Building. The building is home today to Joseph Papp Public Theater.

- The Astor Place subway station (4, 6, and <6> trains) is among the original 28 subway stations, and is on the List of Registered Historic Places in New York. The tile mosaics on the station platform feature beavers, a tribute to John Jacob Astor, whose fortune was founded in beaver-pelt trading.[19]: 4–5 [20]: 8

- The Peter Cooper Memorial by Augustus Saint Gaudens is one block south on Cooper Square.

- 21 Astor Place (also known as "Clinton Hall" and "13 Astor Place") stands on the site which was once the Astor Opera House. After the Astor Place riot, the building was turned over to the New York Mercantile Library, which used it until 1890, when they tore it down and built the current 11-story building. The Library left in 1932, and the building became the headquarters for a union. It has now been redeveloped into modern condominiums behind the original 19th century façade, an example of the technique of facadism.[21]

- The Cooper Station Post Office, built in the 1920s, is just three blocks north.

- The last Kmart in Manhattan was located in Astor Place before its closure in July 2021,[22] in the space first created as a Wanaker's department store.[23] A Wegmans supermarket opened in the former Kmart space in October 2023.[24]

Transportation

[edit]The IRT Lexington Avenue Line of the New York City Subway has a station named Astor Place at the intersection of Lafayette & East 8th Streets, which is served by the 4, 6, and <6> trains.

No bus route serves the first block of Astor Place. The second block is used by the eastbound M8 (westbound buses use East 9th Street) and the uptown M101 and M102 out of service from Cooper Square, making their first stops at Third Avenue.[25]

Gallery

[edit]-

The Astor Library, seen in a 1900 drawing, opened in 1849. It is now the Public Theater

-

The Astor Place riot in 1849: anti-British feelings expressed in a dispute over competing productions of Macbeth; the Astor Opera House is in the background

-

After the riot, the Opera House closed and the building was turned over to the New York Mercantile Library, who later built this 11-story building on the site

-

The Cooper Union Foundation Building has stood on Astor Place, anchoring the north end of Cooper Square, since 1859

-

The Astor Place Building at 444 Lafayette Street was built in 1876…

-

…while across the street stands the modern condominium building at 445 Lafayette (2004)

-

The beaver in the Astor Place subway station is a tribute to John Jacob Astor, whose fortune was founded on beaver-pelt trading

-

Tony Rosenthal's Alamo; behind it, Kmart in 770 Broadway, once the annex to the giant Wanamaker's Department Store

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Elsroad, Linda. "Astor Place" in Jackson, Kenneth T., ed. (1995). The Encyclopedia of New York City. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 0300055366. p.64

- ^ a b Moscow, Henry (1978). The Street Book: An Encyclopedia of Manhattan's Street Names and Their Origins. New York: Hagstrom Company. ISBN 978-0-8232-1275-0.

- ^ a b c "Reconstruction of Astor Place and Cooper Square" New York City Department of Transportation (January 6, 2011)

- ^ a b Warerkar, Tanay (November 16, 2016). "Long-awaited Astor Place reconstruction is finally complete". Curbed NY. Retrieved July 18, 2019.

- ^ Federal Writers' Project (1939). New York City Guide. New York: Random House. pp. 113, 121. ISBN 978-1-60354-055-1. (Reprinted by Scholarly Press, 1976; often referred to as WPA Guide to New York City.)

- ^ "Tribes of New York".

- ^ Walsh, Kevin (November 1999). "The Street Necrology of Greenwich Village". Forgotten NY. Retrieved August 17, 2015.

- ^ Henderson, Mary C. (2004). The City and the Theatre: The History of New York Playhouses, a 250-year Journey from Bowling Green to Times Square. New York: Back Stage Books. ISBN 0-8230-0637-9. p.61

- ^ Caldwell, Mark (2005). New York Night: The Mystique and Its History. New York: Scribner. ISBN 0-7432-7478-4. p.138

- ^ Dunlap, David W. (October 21, 2015). "New York Says Farewell to American Bible Society, and Its Building". New York Times. Retrieved October 23, 2015.

- ^ Federal Writers' Project (1939). New York City Guide. New York: Random House. ISBN 978-1-60354-055-1. (Reprinted by Scholarly Press, 1976; often referred to as WPA Guide to New York City.), pp.121–122

- ^ Dailey, Jessica (September 26, 2013). "See Updated Designs For Long-Awaited Astor Place Revamp". Curbed. Retrieved September 9, 2014.

- ^ Dailey, Jessica (September 16, 2013). "Major Astor Place Reconstruction Is Actually Starting". Curbed. Retrieved September 9, 2014.

- ^ "Astor Place Reconstruction Brings 42,000 Square Feet of New Pedestrian Space to the East Village". NYC Department of Design and Construction. Archived from the original on August 12, 2019. Retrieved July 18, 2019.

- ^ a b Moynihan, Colin (November 19, 2005). "The Cube, Restored, Is Back and Turning at Astor Place". The New York Times. Retrieved March 18, 2009.

- ^ Grimes, William (August 1, 2009). "Tony Rosenthal, 94, Sculptor of Public Art". The New York Times. Retrieved July 17, 2010.

- ^ "Astor Place Cube Will Stay in Place". The New York Times. November 23, 1967. p. 33. Retrieved July 17, 2010.

- ^ Bleyer, Jennifer (January 30, 2005). "A Famous Cube Puzzles Its Biggest Fans". The New York Times. Retrieved July 17, 2010.

- ^ "New York MPS Astor Place Subway Station (IRT)". Records of the National Park Service, 1785 – 2006, Series: National Register of Historic Places and National Historic Landmarks Program Records, 2013 – 2017, Box: National Register of Historic Places and National Historic Landmarks Program Records: New York, ID: 75313927. National Archives.

- ^ "Interborough Rapid Transit System, Underground Interior" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. October 23, 1979. Retrieved November 19, 2019.

- ^ Brozan, Nadine (April 6, 2003). "POSTINGS: On a Triangular Site at 21 Astor Place; 50 Ultramodern Condominiums Behind an Exterior From 1890". The New York Times.

- ^ Offenhartz, Jake (July 12, 2021). "Kmart, An Unlikely Astor Place Icon, Shutters Without Notice". Gothamist. Retrieved July 12, 2021.

- ^ "All that remains of a legendary Astor Place department store few New Yorkers remember". Ephemeral New York. April 10, 2023. Retrieved October 24, 2023.

- ^ "Wegmans officially opens in the East Village". October 18, 2023. Retrieved October 24, 2023.

- ^ "Manhattan Bus Map" (PDF). Metropolitan Transportation Authority. July 2019. Retrieved December 1, 2020.

External links

[edit]- Public Theater

- Demolished Broadway theatres

- The Astor Place Riot

- Pictures of the Cube being removed (The Cube was removed on March 8, 2005, restored, then returned on November 18, 2005.)

- Lincoln's Cooper Union Address