St Pancras, London

| St Pancras | |

|---|---|

St Pancras New Church, Euston Road. | |

Location within Greater London | |

| OS grid reference | TQ305825 |

| London borough | |

| Ceremonial county | Greater London |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | LONDON |

| Postcode district | WC1 |

| Postcode district | NW1 |

| Dialling code | 020 |

| Police | Metropolitan |

| Fire | London |

| Ambulance | London |

| UK Parliament | |

| London Assembly | |

St Pancras (/ˈpæŋkrəs/) is a district in central London. It was originally a medieval ancient parish and subsequently became a metropolitan borough. The metropolitan borough then merged with neighbouring boroughs and the area it covered now forms around half of the modern London Borough of Camden. The area of the parish and borough includes the sub-districts of Camden Town, Kentish Town, Gospel Oak, Somers Town, King's Cross, Chalk Farm, Dartmouth Park, the core area of Fitzrovia and a part of Highgate.

History

[edit]St Pancras Old Church

[edit]St Pancras Old Church lies on Pancras Road, Somers Town, behind St Pancras railway station. Until the 19th century it stood on a knoll on the eastern bank of the now buried River Fleet.

The church, dedicated to the Roman martyr Saint Pancras, gave its name to the St Pancras district, which originated as the parish served by the church. The church is reputed to be one of the oldest sites of Christian worship in England; however, as is so often with old church sites, it is hard to find documentary or archaeological evidence for its initial foundation.

One tradition asserts that the church was established in AD 314 in the late Roman period. There is little to support that view, but it is notable that to the south of the church was a site called The Brill, believed at the time to have been a Roman Camp. The Brill was destroyed during the urbanisation of the area, without any archaeological excavation to assess its age and purpose. The church is certainly very old; it was mentioned in the Domesday Book of 1086, and there is evidence to suggest it predated Domesday by several centuries.

A chapel of ease was subsequently established at Kentish Town to supplement the main parish church, which was replaced by a new building in 1822, St Pancras New Church on the south side of Euston Road. The then-dilapidated Old Church continued in use but was reduced to the status of a chapel of ease. Most of the fabric of the Old Church building dates from a subsequent Victorian restoration.

Ancient Parish

[edit]

The ancient parish of St Pancras (also known as Pancrace or Pancridge[1]) was established in the medieval period to serve five manors: two manors named St Pancras (one prebendial, one lay), Cantlowes (Kentish Town), Tottenham Court and Rugmere (Chalk Farm).[2]

By the end of the nineteenth century, the ancient parish had been divided into 37 ecclesiastical parishes, including one for the old church, to better serve a rapidly growing population. There are currently 17 Church of England parishes completely contained within the boundaries of the ancient parish, all of which benefit from the distributions from the St Pancras Lands Trust and most of which are in South Camden Deanery in the Edmonton Area of the Diocese of London.

Pre-urban period

[edit]In the Middle Ages it had "disreputable associations",[1] and by the 17th century had become the "'Gretna Green' of the London area".[1] On that account Elizabethan playwright Ben Jonson alludes to the area frequently in his plays.[1][a] It was a rural area with a dispersed population until the growth of London in the late eighteenth century.

Urbanisation

[edit]In the 1790s Earl Camden began to develop some fields to the north and west of the old church as Camden Town.[3] About the same time, a residential district was built to the south and east of the church, usually known as Somers Town. In 1822 the new church of St Pancras was dedicated as the parish church. The site was chosen on what was then called the New Road (now Euston Road) which had been built as London's first bypass, the M25 of its day. The two sites are about a kilometre apart. The new church is Grade I listed for its Greek Revival style; the old church was rebuilt in 1847. In the mid-19th century two major railway stations were built to the south of the Old Church, first King's Cross and later St Pancras. The new church is closer to Euston station.

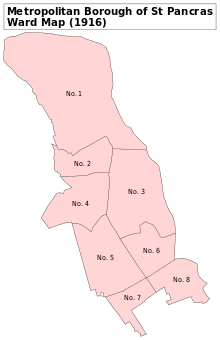

Metropolitan borough

[edit]

The parish of St Pancras was administered by a vestry until the Metropolitan Borough of St Pancras was established in 1900. In 1965 the borough was combined with two others to form the London Borough of Camden.

In the 1950s, St Pancras Council gained a reputation for left-wing radicalism and was referred to as "the most freakish borough in London.”[4] The council refused to take part in civil defence preparations for war which local councils were obliged to provide.[5] The Home Office monitored Mayor John Lawrence, and as of 2016, still refuses Freedom of Information requests related to him on the grounds of protecting national security.[6]

Housing was in excess demand after the damage and disruption of the Second World War. There was strong opposition to the 1957 Rent Act, which led to a series of decisions that caused serious financial difficulty. John Lawrence and several other councillors were expelled from the Labour Party in 1958 but continued to serve as Independent Socialists.[7] The Conservative Party won the 1958 council election.[8]

In 1960, a widespread rent strike in the district led to rioting in September.[9]

St Pancras Battalions

[edit]From 1859 to 1955, the St Pancras produced dedicated military units for the British Army, initially infantry battalions and later anti-aircraft and searchlight regiments. A high proportion of the recruits were drawn from working-class districts of St Pancras, such as Camden Town.

At the start of World War I, the St Pancras Battalion was part of the London Regiment and known as 19th (County of London) Battalion, The London Regiment (St Pancras). The increase in wartime recruitment led to it being split into two battalions (each around a thousand strong), the 1/19th and 2/19th, with the 3/19th established as a training battalion.[10]

These three St Pancras battalions were joined by a fourth, a Pals battalion, which joined a different regiment, the Rifle Brigade (The Prince Consort's Own), as the 16th (Service) Battalion, Rifle Brigade, (St. Pancras), (The Prince Consort's Own). It also established a training battalion, the 17th (Reserve) Battalion, which spent most of the war on Wimbledon Common.[11]

During World War I these three front line battalions were deployed:

- The 1/19th Londons were attached to the 141st (5th London) Brigade, in the 47th (1/2nd London) Division serving on the Western Front.[10]

- The 2/19th Londons, known as Christie’s Minstrels, after their commander and prowess singing while on the march. This battalion was attached to the 180th (2/5th London) Brigade in 60th (2/2nd London) Division, seeing action on the Western front before being moved to the Mediterranean and fighting on the Macedonian front and in the Sinai and Palestine Campaign.[10]

- The 16th (Service) Battalion, Rifle Brigade, or St Pancras Pals, joined the 117th Brigade, part of the 39th Division.[11] That division served on the Western Front, with Sergeant Burman winning a Victoria Cross in 1917.[12] In 1918 the whole Division came close to destruction in the Battle of the Lys.

Geography

[edit]St Pancras was originally an Ancient Parish that ran from a point a little north of Oxford Street, extending north to include part of Highgate, and from today’s Regent's Park in the west to the road now called York Way in the east. These boundaries encompass much of the current London Borough of Camden.

The former River Fleet formed part of the boundary with Clerkenwell,[13] while a tributary of it – later known as Lamb’s Conduit - formed the southern boundary with Holborn. The course of this watercourse is now marked, in part, by Roger Street (formerly known as Henry Street).[14] The tree which gave the Gospel Oak district its name, formed part of the boundary with neighbouring Hampstead.[15]

The boundaries of St Pancras include take in around half of the modern London Borough of Camden, including Camden Town, Kentish Town, Somers Town, Gospel Oak, King's Cross, Chalk Farm, Dartmouth Park, the core area of Fitzrovia and a part of Highgate.

Transport

[edit]There are no motorways in St Pancras, and few stretches of dual carriageway road, but the district has great strategic transport significance to London, due to the presence of three of the capital's most important rail termini; Euston, St Pancras and King's Cross, which are lined up along the Euston Road.

The position of the railway termini on Euston Road, rather than in a more central position further south, is a result of the influential recommendations of a Royal Commission of 1846 which sought to protect the West End districts a short distance south of the road.[16]

National Rail stations include London King's Cross and St Pancras. St Pancras is one of the best-known railway stations in England. It has been extended and is now the terminus for the Eurostar services through the Channel Tunnel. London Underground stations include King's Cross St Pancras.

Landmarks

[edit]Immediately to the north of St Pancras churchyard is St Pancras Hospital, once the parish workhouse and later the London Hospital for Tropical Diseases.

Cemeteries

[edit]

During the 18th and 19th centuries, St Pancras was famous for its cemeteries. In addition to the graveyard of Old St Pancras Church, it also contained the cemeteries of the neighbouring ecclesiastical parishes of St James's Church, Piccadilly, St Giles in the Fields, St Andrew, Holborn, St. George's Church, Bloomsbury, and St George the Martyr, Holborn.[17] These were all closed under the Extramural Interment Act in 1854; the parish was required to purchase land some distance away, beyond its borders, and chose East Finchley for its new St Pancras Cemetery.[18]

The disused graveyard at St Pancras Old Church was left alone for over thirty years until the building of the Midland Railway required the removal of many of the graves. Thomas Hardy, then a junior architect and later a novelist and poet, was involved in this work. He placed a number of gravestones around a tree, now known as "the Hardy Tree".[19] The cemetery was disturbed again in 2002–03 by the construction of the Channel Tunnel Rail Link but much more care was given to the removal of remains than in the 19th century. Old St Pancras Church and its graveyard have links to Charles Dickens, Thomas Hardy, and the Wollstonecraft circle.[19]

Open spaces

[edit]Open spaces in the district include:

|

|

Political divisions

[edit]The name “St Pancras” survives in the name of the local parliamentary constituency, Holborn and St. Pancras. One of the political wards in Camden is called St Pancras and Somers Town; however, ward boundaries are chosen to divide a borough into roughly equal slices with little regard to historical boundaries or day-to-day usage. Besides Somers Town and the area around St Pancras Old Church, the ward includes much of Camden Town and the former Kings Cross Goods Yard, which is being redeveloped as a mixed-use district under the name Kings Cross Central.

Notable residents

[edit]- Alice Barth, soprano

- Walter Alfred Cox, engraver

- AJ Dixon, racing driver

- Ada Ferrar, actress

- Monica Charlot, historian

- Elizabeth Eiloart, writer

- Beatrice Ferrar, actress

- Reg Freeson, politician

- William Hartnell, actor

- Barnaby Kay, actor

- John Lawrence, political activist

- Andrew Lincoln, actor

- Glyndwr Michael, homeless man whose body was used for the Operation Mincemeat deception in WWII.

- Lulu Valli, actress

- W. B. Yeats, poet

- John William Fisher Beaumont, justice

Footnotes

[edit]- ^ This is the foundation for the expression "Pancridge Parson", i.e. a minister who will "perform suden or irregular marriages".[1]

Notes

[edit]- ^ a b c d e Chalfant, pp. 136–

- ^ Lovell, Percy; Marcham, William McB. (1938). "'Introduction', in Survey of London: Volume 19, the Parish of St Pancras Part 2: Old St Pancras and Kentish Town". London: British History Online. pp. 1–31. Retrieved 13 April 2021.

- ^ Richardson.

- ^ Mathieson, p. 86.

- ^ Mathieson, p. 110.

- ^ Mathieson, p. 215.

- ^ Mathieson, p. 154.

- ^ Mathieson, p. 158.

- ^ Mathieson, p. 180.

- ^ a b c James, pp. 114–6.

- ^ a b James, p. 111.

- ^ "IWM record of the medal".

- ^ Temple, Philip (2008). "'West of Farringdon Road', in Survey of London: Volume 47, Northern Clerkenwell and Pentonville". London: British History Online. pp. 22–51. Retrieved 3 August 2020.

- ^ The History of the River Fleet, UCL Fleet Restoration Team, 2009

- ^ "Local history website". 29 August 2013.

- ^ "On the 1846 Royal Commission". London Transport Museum.

- ^ Hinson, Colin (2003). "St. Pancras". GENUKI: UK & Ireland Genealogy. Retrieved 25 February 2017.

- ^ "History". St Pancras International. HS1 Ltd. Retrieved 25 February 2017.

- ^ a b "The Hardy Tree, St Pancras Churchyard, London". The Victorian Web. 17 April 2006. Retrieved 25 February 2017.

References

[edit]- Fran C. Chalfant (1 July 2008). Ben Jonson's London: A Jacobean Placename Dictionary. University of Georgia Press. ISBN 978-0-8203-3291-8..

- Brig E.A. James, British Regiments 1914–18, London: Samson Books, 1978, ISBN 0-906304-03-2/Uckfield: Naval & Military Press, 2001, ISBN 978-1-84342-197-9.

- Mathieson, David (2016). Radical London in the 1950s. Stroud, UK: Amberley. ISBN 9781445661032..

- John Richardson, Camden Town and Primrose Hill Past, 1991, ISBN 0-948667-12-5.

![]() Media related to St Pancras, London at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to St Pancras, London at Wikimedia Commons