Fluxus

Fluxus was an international, interdisciplinary community of artists, composers, designers, and poets during the 1960s and 1970s who engaged in experimental art performances which emphasized the artistic process over the finished product.[1][2] Fluxus is known for experimental contributions to different artistic media and disciplines and for generating new art forms. These art forms include intermedia, a term coined by Fluxus artist Dick Higgins;[3][4][5][6] conceptual art, first developed by Henry Flynt,[7][8] an artist contentiously associated with Fluxus; and video art, first pioneered by Nam June Paik and Wolf Vostell.[9][10][11] Dutch gallerist and art critic Harry Ruhé describes Fluxus as "the most radical and experimental art movement of the sixties".[12][13]

They produced performance "events", which included enactments of scores, "Neo-Dada" noise music, and time-based works, as well as concrete poetry, visual art, urban planning, architecture, design, literature, and publishing. Many Fluxus artists share anti-commercial and anti-art sensibilities. Fluxus is sometimes described as "intermedia". The ideas and practices of composer John Cage heavily influenced Fluxus, especially his notions that one should embark on an artwork without a conception of its end, and his understanding of the work as a site of interaction between artist and audience. The process of creating was privileged over the finished product.[14] Another notable influence were the readymades of Marcel Duchamp, a French artist who was active in Dada (1916 – c. 1922). George Maciunas, largely considered to be the founder of this fluid movement, coined the name Fluxus in 1961 to title a proposed magazine.[15]

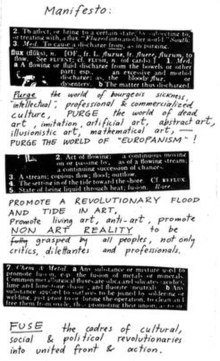

Many artists of the 1960s took part in Fluxus activities, including Joseph Beuys, Willem de Ridder, George Brecht, John Cage, Robert Filliou, Al Hansen, Dick Higgins, Bengt af Klintberg, Alison Knowles, Addi Køpcke, Yoko Ono, Nam June Paik, Shigeko Kubota, La Monte Young, Mary Bauermeister, Joseph Byrd, Ben Patterson, Daniel Spoerri, Ken Friedman, Terry Riley and Wolf Vostell. Not only were they a diverse community of collaborators who influenced each other, they were also, largely, friends. They collectively had what were, at the time, radical ideas about art and the role of art in society.[16] Fluxus founder George Maciunas proposed a well known manifesto, but few considered Fluxus to be a true movement,[17][18] and therefore the manifesto was not largely adopted. Instead, a series of festivals in Wiesbaden, Copenhagen, Stockholm, Amsterdam, London, and New York, gave rise to a loose but robust community with many similar beliefs. In keeping with the reputation Fluxus earned as a forum of experimentation,[12] some Fluxus artists came to describe Fluxus as a laboratory.[19][20]

Early History, Late 50s to 1965

[edit]Origins

[edit]

The origins of Fluxus lie in many of the concepts explored by composer John Cage in his experimental music of the 1930s through the 1960s. After attending courses on Zen Buddhism taught by D. T. Suzuki, Cage taught a series of classes in experimental composition from 1957 to 1959 at the New School for Social Research in New York City. These classes explored the notions of chance and indeterminacy in art, using music scores as a basis for compositions that could be performed in potentially infinite ways. Some of the artists and musicians who became involved in Fluxus, including Jackson Mac Low, La Monte Young, George Brecht, Al Hansen, and Dick Higgins attended Cage's classes.[21][22] A major influence is found in the work of Marcel Duchamp.[23] Also of importance was Dada Poets and Painters, edited by Robert Motherwell, a book of translations of Dada texts that was widely read by members of Fluxus.[24] The term anti-art, a precursor to Dada, was coined by Duchamp around 1913, when he created his first readymades from found objects (ordinary objects found or purchased and declared art).[25] Indifferently chosen, readymades and altered readymades challenged the notion of art as an inherently optical experience, dependent on academic art skills. The most famous example is Duchamp's altered readymade Fountain (1917), a work which he signed "R. Mutt." While taking refuge from WWI in New York, in 1915 Duchamp formed a Dada group with Francis Picabia and American artist Man Ray. Other key members included Arthur Cravan, Florine Stettheimer, and the Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven, credited by some with proposing the idea for Fountain to Duchamp.[26] By 1916 these artists, especially Duchamp, Man Ray, and Picabia, became the center for radical anti-art activities in New York City. Their artworks would inform Fluxus and conceptual art in general.[23] In the late 1950s and very early 1960s, Fluxus and contemporaneous groups or movements, including Happenings, Nouveau réalisme, mail art, and action art in Japan, Austria, and other international locations were, often placed under the rubric of Neo-Dada".[27]

A number of other contemporary events are credited as either anticipating Fluxus or as constituting proto-Fluxus events.[23] The most commonly cited include the series of Chambers Street loft concerts, in New York, curated by Yoko Ono and La Monte Young in 1961, featuring pieces by Ono, Jackson Mac Low, Joseph Byrd, and Henry Flynt;[28] the month-long Yam festival held in upstate New York by George Brecht and Robert Watts in May 1963 with Ray Johnson and Allan Kaprow (the culmination of a year's worth of Mail Art pieces);[23] and a series of concerts held in Mary Bauermeister's studio, Cologne, 1960–61, featuring Nam June Paik and John Cage among many others. It was at one of these events in 1960, during his Etude pour Piano, that Paik leapt into the audience and cut John Cage's tie off, ran out of the concert hall, and then phoned the hall's organisers to announce the piece had ended.[29] As one of the movement's founders, Dick Higgins, stated:

Fluxus started with the work, and then came together, applying the name Fluxus to work which already existed. It was as if it started in the middle of the situation, rather than at the beginning.[30][31]

From the Neo-Dada Anthology of Chance Operations to Early Fluxus

[edit]In 1961 the American musician/artist La Monte Young had been enlisted to guest-edit an East Coast issue of the Wast Coast literary journal Beatitude to be called Beatitude East. But as the Beatitude connection was prematurly terminated, George Maciunas, a trained graphic designer, asked Young if he could layout and help publish the Neo-Dada material.[32] Maciunas supplied the paper, design, and some money for publishing the anthology which contained the work of New York avant-garde artists from that time. The project took the title of An Anthology of Chance Operations from its full title An Anthology of chance operations concept art anti-art indeterminacy improvisation meaningless work natural disasters plans of action stories diagrams Music poetry essays dance constructions mathematics compositions. An Anthology of Chance Operations was completed and published in 1963 by Jackson Mac Low and La Monte Young, as Maciunas had by then moved to Germany to escape his creditors.[33] After opening a short-lived art gallery on Madison Avenue, which showed work by Dick Higgins, Yoko Ono, Jonas Mekas, Ray Johnson, Henry Flynt and La Monte Young, Maciunas moved to Wiesbaden, West Germany, having taken a job as a graphic designer with the US Air Force in late 1961[34] after the gallery had gone bust. From Wiesbaden, Maciunas continued his contact with Young and other New York City-based artists and with expatriate American artists like Benjamin Patterson and Emmett Williams, whom he met in Europe. By September 1962, Maciunas was joined by Dick Higgins and Alison Knowles who traveled to Europe to help him promote a second planned publication to be called Fluxus, the first of a series of yearbooks of artists' works. Maciunas had first come up with the title Fluxus for a never done anthology of New York's Lithuanian artists, but instead applied the term to artists working in the Anthology of Chance Operations vein.[35] Because after fleeing Lithuania at the end of World War II, his family settled in New York, where he first met the group of avant-garde artists and musicians centered around John Cage and La Monte Young. Thus Maciunas coined the name Fluxus not for his perceived group of Lithuania artists but for the Neo-Dada art being produced by a range of artists with a shared sensibility as an attempt to "fuse... cultural, social, & political revolutionaries into [a] united front and action".[36]

Maciunas first publicly coined the term Fluxus (meaning 'to flow') in a 'brochure prospectus' that he distributed to the audience at a festival he had organized, called Après Cage; Kleinen Sommerfest (After Cage; a Small Summer Festival), in Wuppertal, West Germany, 9 June 1962.[37]

Maciunas was an avid art historian, and initially referred to fluxus as 'neo-dadaism' or 'renewed dadaism'.[38] He wrote a number of letters to Raoul Hausmann, an original dadaist, outlining his ideas. Hausmann discouraged the use of the term;

I note with much pleasure what you said about German neodadaists—but I think even the Americans should not use the term "neodadaism" because neo means nothing and -ism is old-fashioned. Why not simply "Fluxus"? It seems to me much better, because it's new, and dada is historic.[39]

As part of the festival, Maciunas wrote a lecture entitled 'Neo-Dada in the United States'.[40] After an attempt to define 'Concretist Neo-Dada' art, he explained that Fluxus was opposed to the exclusion of the everyday from art. Using 'anti-art and artistic banalities', Fluxus would fight the 'traditional artificialities of art'.[41] The lecture ended with the declaration "Anti-art is life, is nature, is true reality—it is one and all."[41]

European festivals and the Fluxkits

[edit]

In 1962, Maciunas, Higgins and Knowles traveled to Europe to promote the planned Fluxus publication with concerts of antique musical instruments. With the help of a group of artists including Joseph Beuys and Wolf Vostell, Maciunas eventually organised a series of Fluxfests across Western Europe. Starting with 14 concerts between 1 and 23 September 1962, at Wiesbaden, these Fluxfests presented work by musicians such as John Cage, Ligeti, Penderecki, Terry Riley and Brion Gysin alongside performance pieces written by Higgins, Knowles, George Brecht and Nam June Paik, Ben Patterson, Robert Filliou, and Emmett Williams, amongst many others. One performance in particular, Piano Activities by Philip Corner, became notorious by challenging the important status of the piano in post-war German homes.

The score—which asks for any number of performers to, among other things, "play", "pluck or tap", "scratch or rub", "drop objects" on, "act on strings with", "strike soundboard, pins, lid or drag various kinds of objects across them" and "act in any way on underside of piano"[42]—resulted in the total destruction of a piano when performed by Maciunas, Higgins and others at Wiesbaden. The performance was considered scandalous enough to be shown on German television four times, with the introduction "The lunatics have escaped!"[43]

At the end we did Corner's Piano Activities not according to his instructions since we systematically destroyed a piano which I bought for $5 and had to have it all cut up to throw it away, otherwise we would have had to pay movers, a very practical composition, but German sentiments about this "instrument of Chopin" were hurt and they made a row about it...[44]

At the same time, Maciunas used his connections at work to start printing cheap mass-produced books and multiples by some of the artists that were involved in the performances. The first three to be printed were Composition 1961 by La Monte Young (see it here, An Anthology of Chance Operations edited by Young and Mac Low and Water Yam, by George Brecht. Water Yam, a series of event scores printed on small sheets of card and collected together in a cardboard box, was the first in a series of artworks that Maciunas printed that became known as Fluxkits. Cheap, mass-produced and easily distributed, Fluxkits were originally intended to form an ever-expanding library of modern performance art. Water Yam was published in an edition of 1000 and originally cost $4.[45] By April 1964, almost a year later, Maciunas still had 996 copies unsold.[46]

Maciunas' original plan had been to design, edit and pay for each edition himself, in exchange for the copyright to be held by the collective.[47][48] Profits were to be split 80/20 at first, in favor of the artist.[49] Since most of the composers already had publishing deals, Fluxus quickly moved away from music toward performance and visual art. John Cage, for instance, never published work under the Fluxus moniker due to his contract with the music publishers Edition Peters.[50]

Maciunas seemed to have a fantastic ability to get things done.... if you had things to be printed he could get them printed. It's pretty hard in East Brunswick to get good offset printing. It's not impossible, but it's not so easy, and since I'm very lazy it was a relief to find somebody who could take the burden off my hands. So there was this guy Maciunas, a Lithuanian or Bulgarian, or somehow a refugee or whatever—beautifully dressed—"astonishing looking" would be a better adjective. He was somehow able to carry the whole thing off, without my having to go 57 miles to find a printer.[51]

Since Maciunas was colorblind, Fluxus multiples were almost always black and white.[52]

New York and the FluxShops

[edit]

After his contract with the US Air Force was terminated due to ill health, Maciunas was forced to return to the US on 3 September 1963.[53] Once back in New York, he set about organizing a series of street concerts and opened a new shop, the 'Fluxhall', on Canal Street. 12 concerts, "away from the beaten track of the New York art scene",[54] took place on Canal Street, 11 April to 23 May 1964. With photographs taken by Maciunas himself, pieces by Ben Vautier, Alison Knowles and Takehisa Kosugi were performed in the street for free, although in practice there was 'no audience to speak of'[54] anyway.

The people in Fluxus had understood, as Brecht explained, that "concert halls, theaters, and art galleries" were "mummifying". Instead, these artists found themselves "preferring streets, homes, and railway stations...." Maciunas recognized a radical political potential in all this forthrightly anti-institutional production, which was an important source for his own deep commitment to it. Deploying his expertise as a professional graphic designer, Maciunas played an important role in projecting upon Fluxus whatever coherence it would later seem to have had.[55]

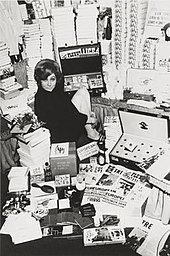

Along with the New York shop, Maciunas built up a distribution network for the new art across Europe and later outlets in California and Japan. Gallery and mail order outlets were established in Amsterdam, Villefranche-Sur-Mer, Milan and London, amongst others.[56] By 1965, the first anthology Fluxus 1 was available, consisting of manila envelopes bolted together containing work by numerous artists who would later become famous including La Monte Young, Christo, Joseph Byrd and Yoko Ono. Other pieces available included packs of altered playing cards by George Brecht, sensory boxes by Ay-O, a regular newsletter with contributions by artists and musicians such as Ray Johnson and John Cale, and tin cans filled with poems, songs and recipes about beans by Alison Knowles (see).

Stockhausen's Originale

[edit]

After returning to New York, Maciunas became reacquainted with Henry Flynt,[57] who encouraged members of Fluxus to take a more overtly political stance. One of the results of these discussions was to set up a picket line at the American premiere of Originale, a recent work by the German composer Karlheinz Stockhausen, 8 September 1964.[58] Stockhausen was deemed a 'Cultural Imperialist' by Maciunas and Flynt, while other members vehemently disagreed. The result was members of Fluxus, such as Nam June Paik and Jackson Mac Low, crossing a picket line made up of other members, including Ben Vautier and Takako Saito[59] who handed out leaflets denouncing Stockhausen as "a characteristic European-North American ruling-class Artist".[60] Dick Higgins participated in the picket, and then coolly joined the other performers inside;[61]

Maciunas and his friend Henry Flynt tried to get the Fluxus people to march around outside the circus with white cards that said Originale was bad. And they tried to say that the Fluxus people who were in the circus weren't Fluxus any more. That was silly, because it made a split. I thought it was funny, and so first I walked around with Maciunas and with Henry with a card, then I went inside and joined the circus; so both groups got angry with me. Oh well. Some people say that Fluxus died that day—I once thought so myself—but it turned out I was wrong.[62]

The event, arranged by Charlotte Moorman as part of her 2nd Annual New York Avant Garde Festival, would cement animosities between Maciunas and her,[63] with Maciunas frequently demanding that artists associated with Fluxus have nothing to do with the annual festival, and would often expel artists who ignored his demands. This hostility continued throughout Maciunas' life—much to Moorman's bemusement—despite her continued championing of Fluxus art and artists.[64]

Middle Fluxus History: 1965–78

[edit]Perceived insurgencies and the Asiatic influence

[edit]

The picketing of Originale marked the high point of Maciunas' agitprop approach,[65] an approach that estranged many of Fluxus' early proponents; Jackson Mac Low had resigned immediately after hearing 'antisocial' plans laid in April 1963, such as breaking down trucks under the Hudson River.[66] Brecht threatened to quit on the same issue, and then left New York in the spring of 1965. Despite his continued allegiance to Fluxus ideals, Dick Higgins fell out with Maciunas around the same time, ostensibly over his setting up the Something Else Press which printed many texts by key Fluxus-related personalities and other members of the avant garde. Charlotte Moorman continued to present her Annual Avant Garde Festival in New York.

Such perceived insurrections in the coherence of Maciunas' leadership of Fluxus provided an opening for Fluxus to become increasingly influenced by Japanese members of the group.[67] Since returning to Japan in 1961, Yoko Ono had been recommending colleagues look Maciunas up if they moved to New York; by the time she had returned, in early 1965, Hi Red Center, Shigeko Kubota, Takako Saito, Mieko Shiomi, Yasunao Tone and Ay-O had all started to make work for Fluxus, often of a contemplative nature.[68]

In Tokyo Japan 1964 Yoko Ono, a nonconformist to the Fluxus community,[69] independently published her artist’s book Grapefruit.[70] The book’s text itself encompassing event scores and other forms of participatory art.[71]

An event score from the book:

Cloud Piece[72]

Imagine the clouds dripping.

Dig a hole in your garden to put them in.

Proto-Performance Art

[edit]On September 25, 1965, the FluxOrchestra, with La Monte Young conducting, played at Carnegie Recital Hall in New York City with a poster and program designed by George Maciunas. Copies of the program were folded into paper airplanes and launched during the evening, which included performances of "Falling Event" by Chieko Shiomi, "Symphony No. 3 'On the Floor from 'Clouds Scissors'" by George Brecht, "4 Pieces for Orchestra to La Monte Young" by Yoko Ono, "Disappearing Music for Face" by Shiomi, "Tactical Pieces for Orchestra" and "Olivetti Adding Machine in Memoriam for Adriano Olivetti" by Anthony Cox, "Trance for Orchestra" by Watts, "Sky Piece to Jesus Christ*" by Ono, "Octet for Winds 'In the Water' from 'Cloud Scissors" by Brecht, "Piece" by Shigeko Kubota, "1965 $50" by Young, "Piano Piece" by Tomas Schmit, "Sword Piece" by Cox, "Music for Late Afternoon Together With" by Shiomi, "2" by Watts, "c/t Trace" by Watts, "Intermission Event" by Willem de Ridder, "Moviee Music" by Stan Vanderbeek, "Mechanical Orchestra" by Joe Jones, and "Secret Room" by Ben Vautier.

In 1969, Fluxus artist Joe Jones opened his JJ Music Store (aka Tone Deaf Music Store) at 18 North Moore Street, where he presented his repetitive drone music machines. He created there an installation in the window so that anyone could press numerous door buttons to play the noise music machines displayed there.[73] Jones also presented small musical installation performances there, alone or with other Fluxus artists, such as Yoko Ono and John Lennon,[74] among others. From April 18 to June 12, 1970, Ono and Lennon (aka Plastic Ono Band) presented a series of Fluxus art events and concerts there called GRAPEFRUIT FLUXBANQUET. It was promoted with a poster designed by Fluxus leader George Maciunas. Performances included Come Impersonating John Lennon & Yoko Ono, Grapefruit Banquet (April 11–17) by George Maciunas, Yoshimasa Wada, Nye Ffarrabas (formerly Bici Forbes and Bici Forbes Hendricks), Geoffrey Hendricks, and Robert Watts; Do It Yourself (April 11–17) by Yoko Ono; Tickets by John Lennon + Fluxagents (April 18–24) with Wada, Ben Vautier and Maciunas; Clinic by Yoko Ono + Hi Red Center (April 25-May 1); Blue Room by Yoko + Fluxmasterliars (May 2–8); Weight & Water by Yoko + Fluxfiremen (May 9–15); Capsule by Yoko + Flux Space Center (May 16–22) with Maciunas, Paul Sharits, George Brecht, Ay-O, Ono, Watts, John Cavanaugh; Portrait of John Lennon as a Young Cloud by Yoko + Everybody (May 23–29); The Store by Yoko + Fluxfactory (May 30-June 5), with Ono, Maciunas, Wada, Ay-O; and finally Examination by Yoko + Fluxschool (June 6–12) with Ono, Geoffrey Hendricks, Watts, Mieko Shiomi and Robert Filliou.[75]

Objects blurring boundaries

[edit]As Fluxus gradually became more famous, Maciunas' ambitions for the sale of cheap multiples grew. The second flux-anthology, the Fluxkit (late 1964),[76] collected together early 3D work made by the collective in a businessman's case, an idea borrowed directly from Duchamp's Boite en Valise[77][78] Within a year, plans for a new anthology, Fluxus 2, were in full swing to contain Flux films by John Cage and Yoko Ono (with hand held projectors provided), disrupted matchboxes and postcards by Ben Vautier, plastic food by Claes Oldenburg, FluxMedicine by Shigeko Kubota (containing empty pill packages), and artworks made of rocks, ink stamps, outdated travel tickets, undoable puzzles and a machine to facilitate humming.[79]

Maciunas' belief in the collective extended to authorship; a number of pieces from this period were anonymous, mis-attributed, or have had their authorship since questioned.[80] As a further complication, Maciunas was in the habit of dramatically changing ideas submitted by various artists before he put the works into production. Solid Plastic in Plastic Box, credited to Per Kirkeby 1967, for instance, had originally been realised by Kirkeby as a metal box, inscribed 'This Box Contains Wood'. When opened, the box would be found to contain sawdust. By the time the multiple had been manufactured by Maciunas, it was a block of solid plastic contained in a plastic box of the same color.[78] Conversely, Maciunas assigned Degree Face Clock, in which a clock face is measured out in 360°, to Kirkeby despite being an idea by Robert Watts;[81]

Some years ago, when I spoke with Robert Watts about Degree Face Clock and Compass Face Clock, he had recalled thinking up the idea himself and was surprised that George Maciunas advertised them as Per Kirkeby's. Watts shrugged and said that was the way George worked. There would be ideas in the air and Maciunas would assign the piece to one artist or another.[82]

Other tactics from this time included Maciunas buying large amounts of plastic boxes wholesale, and handing them out to artists with the simple request to turn them into Fluxkits, and the use of the rapidly growing international network of artists to contribute items needed to complete works. Robert Watts' Fluxatlas, 1973, for instance, contains small rocks sent by members of the group from around the world.[83]

Inventing Performance Art

[edit]In addition to his numerous original compositions which have joined the collective's catalog of works, Larry Miller, associated with the group since 1969, has also been active as an interpreter of the "classic" scores and responsible for bringing the group's works to a wider public, blurring the lines between artist, producer and researcher. Besides Miller's own artistic work, he has also organized, reconstructed and performed at numerous Fluxus events and assembled an extensive collection of material on the history of Fluxus.[84] Through Miller, Fluxus attracted media coverage such as the worldwide CNN coverage of Off Limits exhibit at Newark Museum, 1999.[85] Other Miller activities as organizer, performer and presenter within the Fluxus milieu include Performance in Fluxus Continue 1963–2003 at Musee d'Art et d'Art Contemporain in Nice; Fluxus a la Carte in Amsterdam; and Centraal Fluxus Festival at Centraal Museum, Utrecht, Netherlands. In 2004, for Geoff Hendricks' Critical Mass: Happenings, Fluxus, Performance, Intermedia and Rutgers University 1958–1972, Miller reprised and updated the track and field events of the Flux Olympics, first presented in 1970.[86] For Do-it Yourself Fluxus at AI – Art Interactive – in Cambridge, Massachusetts, Miller worked as the curatorial consultant for an exhibit of works that allowed viewers hands-on experience including the reconstruction of several sections of the historic Flux Labyrinth, a massive and intricate maze that Miller originally constructed with George Maciunas at Akademie der Künste, Berlin in 1976 and which included sections by several of the Fluxus artists. Miller created a new version of the Flux Labyrinth at the In the Spirit of Fluxus exhibit at the Walker Art Center in 1994, where Griel Marcus said, "Miller was... fine tuning the monster."[87]

Feminism

[edit]Women associated with Fluxus such as Carolee Schneemann and Charlotte Moorman, and founding members of the group such as Alison Knowles and Yoko Ono, contributed works in varying media and with differing content such as Knowles' "Make a Salad" and "Make a Soup.". Each was shaped by their times and their associations with artists of the previous generation such as Sari Dienes who were pointing the way to the changes of the 1960s and 70s with strong personnas and art.[88] Some made experimental and performative work having to do with the body that created a powerful female presence, which existed within Fluxus from the group's beginning as illustrated by works including Carolee Schneemann's "Interior Scroll", Yoko Ono's "Cut Piece", and Shigeko Kubota's "Vagina Painting". Women working within Fluxus were often simultaneously critiquing their position within a male dominated society while also exposing the inequalities within an art collective that claimed to be open and diverse. George Maciunas, in his rejection of Schneeman as a member of Fluxus, called her "guilty of Baroque tendencies, overt sexuality, and theatrical excess".[89] "Interior Scroll" was a response to Schneemann's experience as a filmmaker in the 1950s and 1960s, when male filmmakers claimed that women should restrict themselves to dance.

He said we are fond of you

You are charming

But don't ask us

To look at your films

We cannot

There are certain films

We cannot look at

The personal clutter

The persistence of feeling

The hand-touch sensibility— Carolee Schneemann[89]

In An evening with Fluxus women: a roundtable discussion, hosted at New York University on 19 February 2009 by Women & Performance: a journal of feminist theory and the Department of Performance Studies, a passage from Mieko Shiomi reads "...the best thing about Fluxus, I think, is that there was no discrimination on the basis of nationality and gender. Fluxus was open to anyone who shared similar thoughts about art and life. That's why women artists could be so active without feeling any frustration."[90]: 370

Shigeo Kubota's Vagina Painting (1965), was performed by attaching a paintbrush dipped in red paint to her underwear, then applying it to a piece of paper while moving over it in a crouching position. The paint evoked menstrual blood. Vagina Painting has been interpreted as a critique of Jackson Pollock's action paintings, and the male-dominated abstract expressionist tradition.[91]

Utopian communities

[edit]A number of artists in the group were interested in setting up Flux communes, intending to 'bridge the gap between the artist community and the surrounding society'[92] The first of these, La Cédille qui Sourit or The Cedilla That Smiles,[93] was set up in Villefranche-sur-Mer, France, by Robert Filliou and George Brecht, 1965–1968. Intended as an 'International Centre of Permanent Creation', the shop sold Fluxkits and other small wares as well as housing a 'non-school', boasting the motto "A carefree exchange of information and experience. No students, no teachers. Perfect licence, at times to listen at times to talk."[94] In 1966, Maciunas, Watts and others took advantage of new legislation drafted to regenerate the area of Manhattan known as 'Hell's Hundred Acres', soon to become rebranded as SoHo, allowing artists to buy live/work spaces in an area that had been blighted due to a proposed 18-lane expressway along Broome Street.[92] Led by Maciunas, plans were laid to start a series of real-estate developments in the area, designed to create an artists' community within a few streets of the FluxShop on Canal Street.

'Maciunas wanted to establish collective workshops, food-buying cooperatives and theaters to link the strengths of various media together and bridge the gap between the artist community and the surrounding society'

The first warehouse, intended to house Maciunas, Watts, Christo & Jeanne-Claude, Jonas Mekas, La Monte Young and others, was located on Greene Street. Likening these communities to the soviet Kolkhozs, Maciunas didn't hesitate to adopt the title 'Chairman of Bldg. Co-Op'[95] without first registering an office or becoming a member of the New York State Association of Realtors.[96] FluxHousing Co-Operatives continued to redevelop the area over the next decade, and were widened to include plans to set up a FluxIsland- a suitable island was located near Antigua, but the money to buy and develop it remained unforthcoming- and finally a performance arts centre called the FluxFarm established in New Marlborough, Massachusetts. The plans were continually dogged by financial problems, constant run-ins with the New York authorities, and eventually resulted, on 8 November 1975, in Maciunas being severely beaten by thugs sent by an unpaid electrical contractor.[97]

End

[edit]It is arguably said that Fluxus came to an end when its founder and leader George Maciunas died in 1978 from complications due to pancreatic cancer. Maciunas' funeral was held in typical Fluxus style where they dubbed the funeral "Fluxfeast and Wake", ate foods that were only black, white, or purple.[98] Maciunas left behind his thoughts on Fluxus in a series of important video conversations called Interview With George Maciunas with Fluxus artist Larry Miller, which has been screened internationally and translated into numerous languages.[99] Over the past 30 years, Miller has shot and collected Fluxus related materials including tapes on Joe Jones, Carolee Schneemann, Ben Vautier, Dick Higgins, and Alison Knowles, in addition to the 1978 Maciunas interview.

Fluxus since 1978

[edit]Maciunas moved to the Berkshire Mountains in Western Massachusetts in the late 1970s. Two decades earlier, after collecting paintings, the Boston art collector Jean Brown, and her late husband Leonard Brown, began to shift their focus to Dadaist and Surrealist art, manifestoes and periodicals. In 1971, after Mr. Brown's death, Mrs. Brown moved to Tyringham, and expanded into areas adjacent to Fluxus, including artists' books, concrete poetry, happenings, mail art and performance art. Maciunas helped turn her home, originally a Shaker seed house, into an important center for both Fluxus artists and scholars, with Mrs. Brown alternately cooking meals and showing guests her collection. Activities centered on a large archive room on the second floor built by Maciunas, who settled in nearby Great Barrington, where it was discovered that Maciunas developed cancer of the pancreas and liver in 1977.

Three months before his death, he married his friend and companion, the poet Billie Hutching. After a legal wedding in Lee, Massachusetts, the couple performed a "Fluxwedding" in a friend's loft in SoHo, 25 February 1978. A videotape of the Maciunas' wedding was produced by Dimitri Devyatkin.[100] The bride and groom traded clothing.[101] Maciunas died on 9 May 1978 in a hospital in Boston.

After the death of George Maciunas a rift opened in Fluxus between a few collectors and curators who placed Fluxus as an art movement in a specific time frame (1962 to 1978), and the artists themselves, many of whom continued to see Fluxus as a living entity held together by its core values and world view. Different theorists and historians adopted each of these views. Fluxus is therefore referred to variously in the past or the present tense. While the definition of Fluxus was always a subject of controversy, the question is now significantly more complex due to the fact that many of the original artists who were still living when Maciunas died are now dead themselves.[102][103]

Some have argued that the unique control that curator Jon Hendricks holds over a major historical Fluxus collection (the Gilbert and Lila Silverman collection) has enabled him to influence, through the numerous books and catalogues subsidized by the collection, the view that Fluxus died with Maciunas. Hendricks argues that Fluxus was a historical movement that occurred at a particular time, asserting that such central Fluxus artists as Dick Higgins and Nam June Paik could no longer label themselves as active Fluxus artists after 1978, and that contemporary artists influenced by Fluxus cannot lay claim to be Fluxus artists.[104][105] The Museum of Modern Art makes the same claim dating the movement to the 1960s and 1970s.[23][106] However, the influence of Fluxus continues today in multi-media digital art performances. In September, 2011 Other Minds presented a performance at the SOMArts building in San Francisco to celebrate the 50th anniversary of Fluxus.[107][108] The performance was curated by Adam Fong who was also one of the performers along with Yoshi Wada, Alison Knowles, Hannah Higgins, Luciano Chessa and Adam Overton.

Others, including Hannah Higgins, daughter of fluxus artists Alison Knowles and Dick Higgins, assert that although Maciunas was a key participant, there were many more, including Fluxus co-founder Higgins, who continued to work within Fluxus after the death of Maciunas.[109] The rise of the Internet in the 1990s enabled a vibrant post-Fluxus community to emerge online. After some of the original Fluxus artists from the 1960s and 1970s including Higgins, created online communities such as the Fluxlist, following their departure, younger artists, writers, musicians, and performers have attempted to continue their work in cyberspace. Many of the original Fluxus artists still working enjoy homages by younger Fluxus-influenced artists who stage events to commemorate Fluxus, but discourage the use of the "Fluxus" label by younger artists.[110][111]

In 2018 the Los Angeles Philharmonic in its Fluxus Festival presented a fluxus performance incorporating John Cage's "Europeras 1 and 2" directed by Yuval Sharon.[112] Fluxus artists continue to perform today on a smaller scale.

Influences

[edit]An immediate predecessor of Fluxus, according to Maciunas, was the Gutai group which promoted art as an anti-academic, psychophysical experience, an "art of matter as it is" as explained by Shiraga Kazuo in 1956. Gutai became connected with a sort of artistic mass-production, anticipating Fluxus's trademark, i.e., ambiguity between the cultivated and the trivial, between high and low. Indeed, avant-garde art in Japan tended toward informal rather than conceptual elements, radically opposing the extreme formality and symbolism found in Japanese art.

In the 1950s New York music scene there could be discerned many issues related to the post-war disenchantment experienced by many throughout the developed world. Such disillusionment in itself presented a case for commitment to Buddhism and Zen in everyday matters such as mental attitude, meditation, and approach to food and body care. It was also felt, however, that there was a general need for a more radical artistic sensibility. The themes of decay and of the inadequacy of the idea of modernity in artistic fields were adopted, partly from Duchamp and Dada and partly from consciousness of the uneasiness of living in contemporary society.

It is said that Fluxus challenged notions of representation, offering instead simple presentation. This, in fact, corresponds to a major difference between Western and Japanese art. Another important Fluxus characteristic was the elimination of perceived boundaries between art and life, a very prominent trend in post war art. This was exemplified by the work and writings of Josheph Beuys who stated, "every man is an artist." Fluxus's approach was an everyday, "economic" one as seen in the production of small objects made of paper and plastic. Again, this strongly corresponds with some of the fundamental characteristics of Japanese culture, i.e., the high artistic value of everyday acts and objects and the aesthetic appreciation of frugality. This also links with Japanese art, and the concept of shibumi, which may involve incompleteness, and supports the appreciation of bare objects, emphasizing subtlety rather than overtness. The renowned Japanese aesthetics scholar Onishi Yoshinori called the essence of Japanese art pantonomic because of the consciousness of no distinction between nature, art and life. Art is the way to approach life and nature/reality corresponding to actual existence.[113]

Fluxus art

[edit]Fluxus encouraged a "do-it-yourself" aesthetic, and valued simplicity over complexity. Like Dada before it, Fluxus included a strong current of anti-commercialism and an anti-art sensibility, disparaging the conventional market-driven art world in favor of an artist-centered creative practice. As Fluxus artist Robert Filliou wrote, however, Fluxus differed from Dada in its richer set of aspirations, and the positive social and communitarian aspirations of Fluxus far outweighed the anti-art tendency that also marked the group.[114]

Among its early associates were Joseph Beuys, Dick Higgins, Davi Det Hompson, Nam June Paik, Wolf Vostell, La Monte Young, Joseph Byrd, Al Hansen and Yoko Ono who explored media ranging from performance art to poetry to experimental music to film. Taking the stance of opposition to the ideas of tradition and professionalism in the arts of their time, the Fluxus group shifted the emphasis from what an artist makes to the artist's personality, actions, and opinions. Throughout the 1960s and 1970s (their most active period) they staged "action" events, engaged in politics and public speaking, and produced sculptural works featuring unconventional materials. Their radically untraditional works included, for example, the video art of Nam June Paik and Charlotte Moorman and the performance art of Joseph Beuys and Wolf Vostell. During the early years of Fluxus, the often playful style of the Fluxus artists resulted in them being considered by some to be little more than a group of pranksters. Fluxus has also been compared to Dada and aspects of Pop Art and is seen as the starting point of mail art and no wave artists. Artists from succeeding generations such as Mark Bloch do not try to characterize themselves as Fluxus but create spinoffs such as Fluxpan or Jung Fluxus as a way of continuing some of the Fluxus ideas in a 21st-century, post-mail art context.

In terms of an artistic approach, Fluxus artists preferred to work with whatever materials were at hand, and either created their own work or collaborated in the creation process with their colleagues. Outsourcing part of the creative process to commercial fabricators was not usually part of Fluxus practice. Maciunas personally hand-assembled many of the Fluxus multiples and editions.[115] While Maciunas assembled many objects by hand, he designed and intended them for mass production.[23][116] Where multiple publishers produced signed, numbered objects in limited editions intended for sale at high prices, Maciunas produced open editions at low prices.[23][116] Several other Fluxus publishers produced different kinds of Fluxus editions. The best known of these was the Something Else Press, established by Dick Higgins, probably the largest and most extensive Fluxus publisher, producing books in editions that ran from 1,500 copies to as many as 5,000 copies, all available at standard bookstore prices.[117][118] Higgins created the term "intermedia" in a 1966 essay.[119]

The art forms most closely associated with Fluxus are event scores and Fluxus boxes. Fluxus boxes (sometimes called Fluxkits or Fluxboxes) originated with George Maciunas who would gather collections of printed cards, games, and ideas, organizing them in small plastic or wooden boxes.[120]

Event score

[edit]An event score, such as George Brecht's "Drip Music", is essentially a performance art script that is usually only a few lines long and consists of descriptions of actions to be performed rather than dialogue.[121][122][123] Fluxus artists differentiate event scores from "happenings". Whereas happenings were sometimes complicated, lengthy performances meant to blur the lines between performer and audience, performance and reality, event performances were usually brief and simple. The event performances sought to elevate the banal, to be mindful of the mundane, and to frustrate the high culture of academic and market-driven music and art.

The idea of the event began in Henry Cowell's philosophy of music.[citation needed] Cowell, a teacher to John Cage and later to Dick Higgins, coined the term that Higgins and others later applied to short, terse descriptions of performable work. The term "score" is used in exactly the sense that one uses the term to describe a music score: a series of notes that allow anyone to perform the work, an idea linked both to what Nam June Paik labeled the "do it yourself" approach and to what Ken Friedman termed "musicality." While much is made of the do it yourself approach to art, it is vital to recognize that this idea emerges in music, and such important Fluxus artists as Paik, Higgins, or Corner began as composers, bringing to art the idea that each person can create the work by "doing it." This is what Friedman meant by musicality, extending the idea more radically to conclude that anyone can create work of any kind from a score, acknowledging the composer as the originator of the work while realizing the work freely and even interpreting it in far different ways from those the original composer might have done.

Other creative forms that have been adopted by Fluxus practitioners include collage, sound art, music, video, and poetry—especially visual poetry and concrete poetry.[124]

Use of shock

[edit]Nam June Paik and his peers in the Fluxus art movement thoroughly understood the impact and importance of shock on the viewer. Fluxus artists believed that shock not only makes the viewer question their own reasoning, but is a means to awaken the viewer, "...from a perceptive lethargy furthered by habit."[125] Paik himself described the shock factor in his Fluxus work: "People who come to my concerts or see my objects need to be transferred into another state of consciousness. They have to be high. And in order to put them into this state of highness, a little shock is required... Anyone who came to my exhibition saw the head and was high."[126] Paik's "head" was that of a real cow displayed at the entrance to his exhibition, Exposition of Music—Electronic Television, located in the Galerie Parnass, Wuppertal, Germany in 1963.[125]

Artistic philosophies

[edit]Fluxus is similar in spirit to the earlier art movement of Dada, emphasizing the concept of anti-art and taking jabs at the seriousness of modern art.[127] Fluxus artists used their minimal performances to highlight their perceived connections between everyday objects and art, similarly to Duchamp in pieces such as Fountain.[127] Fluxus art was often presented in "events", which Fluxus member George Brecht defined as "the smallest unit of a situation."[127][128] The events consisted of a minimal instruction, opening the events to accidents and other unintended effects.[129] Also contributing to the randomness of events was the integration of audience members into the performances, realizing Duchamp's notion of the viewer completing the art work.[129]

The Fluxus artistic philosophy has been defined as a synthesis of four key factors that define the majority of Fluxus work:

- Fluxus is intermedia. Fluxus creators like to see what happens when different media intersect. They use found and everyday objects, sounds, images, and texts to create new combinations of objects, sounds, images, and texts.

- Fluxus works are simple. The art is small, the texts are short, and the performances are brief.

- Fluxus is fun. Humor has always been an important element in Fluxus. [citation needed]

Late criticism

[edit]There is a complexity in adequately charting a unified history of Fluxus. In Fluxus: A Brief History and Other Fictions, Owen Smith concedes that, with the emergence of new material published about Fluxus and its expansion into the present, its history must remain open.[130] The resistance to being pigeonholed, and with the absence of a stable identity, Fluxus opened up to wide participation but also, from what would appear in history, closed off that possibility. Maciunas made frequent acts of excommunication between 1962 and 1978 which destabilized the collective.[131] Kristine Stiles argues in one of her essays that the essence of Fluxus is "performative", while recently she feels that essence has been "eroded or threatened". Fluxus instead moved towards favoring the objects of publication, Stiles asserts: "Care must be taken that Fluxus is not transformed historically from a radical process and presentational art into a tradition static and representational art."[130] With no leadership, no identifiable guidelines, no real collective strategy, no homogeneity in terms of practices, Fluxus cannot be handled through traditional critical tools. Fluxus is an indicator of this confusion. Fluxus therefore is nearly always a discourse on the failure of discourse.[132]

Fluxus artists

[edit]Fluxus artists shared several characteristics including wit and "childlikeness", though they lacked a consistent identity as an artistic community.[133] This vague self-identification allowed the group to include a variety of artists, including a large number of women. The possibility that Fluxus had more female members than any Western art group up to that point in history is particularly significant because Fluxus came on the heels of the white male-dominated abstract expressionism movement.[133] However, despite the designed open-endedness of Fluxus, Maciunas insisted on maintaining unity in the collective. Because of this, Maciunas was accused of expelling certain members for deviating from what he perceived as the goals of Fluxus.[134]

Many artists, writers, and composers have been associated with Fluxus over the years, including:

- Eric Andersen (born 1940)

- John Armleder (born 1948)

- Ay-O (born 1931)

- Mary Bauermeister (1934-2023)

- Joseph Beuys (1921–1986)

- Bazon Brock (born 1936)

- Joseph Byrd (born 1937)

- John Cage (1912–1992)[135]

- George Brecht (1926–2008)

- Giuseppe Chiari (1926–2007)

- Henning Christiansen (1932–2008)

- Philip Corner (born 1933)

- Jean Dupuy (1925–2021)

- Felipe Ehrenberg (1943–2017)

- Öyvind Fahlström (1928–1976)

- Robert Filliou (1926–1987)

- Simone Forti (born 1935)

- Henry Flynt (born 1940)

- Ken Friedman (born 1949)

- Al Hansen (1927–1995)

- Martha Hellion (born 1937)

- Geoffrey Hendricks (1931–2018)

- Bici Hendricks (born 1932)

- Dick Higgins (1938–1998)

- Davi Det Hompson (1939–1996)

- Alice Hutchins (1916–2009)

- Toshi Ichiyanagi (born 1933)

- Terry Jennings (1940–1981)

- Ray Johnson (1927–1995)

- Joe Jones (1934–1993)

- Allan Kaprow (1927–2006)

- Bengt af Klintberg (born 1938)

- Milan Knížák (born 1940)

- Alison Knowles (born 1933)

- Arthur Köpcke(1928–1977)

- Takehisa Kosugi (1938–2018)

- Philip Krumm (born 1941)

- Shigeko Kubota (1937–2015)

- George Landow (1944–2011)

- Vytautas Landsbergis (born 1932)

- John Lennon (1940–1980)

- Jackson Mac Low (1922–2004)

- Richard Maxfield (1927–1969)

- George Maciunas (1931–1978)

- Jonas Mekas (1922–2019)

- Gustav Metzger (1926–2017)

- Larry Miller (born 1944)

- Kate Millett (1934–2017)

- Charlotte Moorman (1933–1991)

- Maurizio Nannucci (born 1939)

- Yoko Ono (born 1933)

- Robin Page (1932–2015)

- Nam June Paik (1932–2006)

- Ben Patterson (1934–2016)

- Terry Riley (born 1935)

- Dieter Roth (1930–1998)

- Takako Saito (born 1929)

- Wim T. Schippers (born 1942)

- Tomas Schmit (1943–2006)

- Carolee Schneemann (1939–2019)

- Mieko Shiomi (born 1938)

- Gianni-Emilio Simonetti (born 1940)

- Daniel Spoerri (born 1930)

- James Tenney (1934–2006)

- Yasunao Tone (born 1935)

- Peter Van Riper (1942-1998)

- Ben Vautier (1935-2024)

- Wolf Vostell (1932–1998)

- Yoshi Wada (1943–2021)

- Robert Watts (1923–1988)

- Emmett Williams (1925–2007)

- La Monte Young (born 1935)

Scholars, critics, and curators associated with Fluxus

[edit]

|

|

Major collections and archives

[edit]- Alternative Traditions in Contemporary Art, University Library and University of Iowa Museum of Art, University of Iowa, Iowa City, Iowa, USA

- Archiv Sohm, Staatsgalerie Stuttgart, Stuttgart, Germany

- Archivio Conz, Verona, Italy

- Artpool, Budapest, Hungary

- Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive, Berkeley, California

- Emily Harvey Foundation, New York City, and Venice, Italy

- David Mayor/Fluxshoe/Beau Geste Press papers, Tate Gallery Archive, Tate Britain, London, England[136]

- Fluxeum, collection Ute and Michael Berger, Wiesbaden-Erbenheim, Germany

- Fluxus Collection, Ken Friedman papers, Tate Gallery Archive, Tate Britain, London, England

- Fluxus Collection, Walker Art Center, Minneapolis, Minnesota, USA

- Fondation du Doute[137]

- FONDAZIONE BONOTTO, Molvena, Vicenza, Italy

- Franklin Furnace Archive, The Museum of Modern Art, New York City

- George Maciunas Memorial Collection, The Hood Museum of Art, Dartmouth College, Hanover, New Hampshire, USA

- Gilbert and Lila Silverman, Fluxus Foundation, Detroit, Michigan, and New York City, USA

- Museo Vostell Malpartida[138] Cáceres, Spain

- Museum Fluxus+ Potsdam, Germany[139]

- Jean Brown papers, 1916–1995 finding aid, Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles[140]

- Sammlung Maria und Walter Schnepel, Bremen, Germany

- Institute for the Arts & Science, University of California, Santa Cruz, USA

- De Montfort University, Leicester, UK

- TVF The Endless Story of FLUXUS,[141] Gent, Belgium

- Jonas Mekas Visual Arts Center, Vilnius, Lithuania

- The Israel Museum, Jerusalem, Gift from the Gilbert and Lila Silverman Collection, Detroit, to American Friends of the Israel Museum

- In 2023, Sub Rosa records released a collection of Fluxus sound works on CD entitled Fluxus & NeoFluxus / Stolen Symphony

See also

[edit]

|

Selected bibliography

[edit]- Jürgen Becker, Wolf Vostell, Happenings, Fluxus, Pop Art, Nouveau Réalisme. Eine Dokumentation. Rowohlt Verlag, Reinbek 1965.

- Happening & Fluxus. Kölnischer Kunstverein, 1970.

- Baas, Jacquelynn, Friedman, Ken Fluxus and the Essential Questions of Life. Chicago and Hanover, NH: University of Chicago Press and Hood Museum of Art, 2011. ISBN 978-022-60335-9-4.

- Bernstein, Roslyn, and Shael Shapiro. Illegal Living: 80 Wooster Street and the Evolution of SoHo (Jonas Mekas Foundation), www.illegalliving.com ISBN 978-609-95172-0-9, September 2010.

- Block, René, ed. 1962 Wiesbaden Fluxus 1982. Wiesbaden: Harlekin Art, Museum Wiesbaden, and Nassauischer Kunstverein, 1982.

- Clay, Steve, and Ken Friedman, eds. Intermedia, Fluxus and the Something Else Press: Selected Writings by Dick Higgins. Catskill, New York: Siglio Press, 2018. ISBN 978-1-938221-20-0.

- Chamberlain, Colby, Fluxus Administration: George Maciunas and the Art of Paperwork, University of Chicago Press, 2024 ISBN 022683137X

- Der Traum von Fluxus. George Maciunas: Eine Künstlerbiographie. Thomas Kellein, Walther König, 2007. ISBN 978-3-8656-0228-2.

- Fluxus und Freunde: Sammlung Maria und Walter Schnepel, Katalog zur Ausstellung Neues Museum Weserburg Bremen; Fondazione Morra, Napoli; Kunst Museum Bonn 2002.

- Friedman, Ken, ed. The Fluxus Reader. Chicester, West Sussex and New York: Academy Editions, 1998.

- Gray, John. Action Art. A Bibliography of Artists' Performance from Futurism to Fluxus and Beyond. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press, 1993.

- Haskell, Barbara. BLAM! The Explosion of Pop, Minimalism and Performance 1958–1964. New York: W. W. Norton in association with the Whitney Museum of American Art, 1984.

- Hansen, Al, and Beck Hansen. Playing with Matches. RAM USA, 1998.

- Harren, Natilee. Fluxus Forms: Scores, Multiples, and the Eternal Network. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2020.

- Hapgood, Susan, and Cornelia Lauf. FluxAttitudes. Ghent: Imschoot Uitgevers, 1991.

- Held, John Jr. Mail Art: an Annotated Bibliography. Metuchen, New Jersey and London: Scarecrow Press, 1991.

- Held, John Jr. Where the Secret is Hidden: Collected Essays Breda: TAM-Publications Netherlands, 2011.

- Hendricks, Geoffrey, ed. Critical Mass, Happenings, Fluxus, Performance, Intermedia and Rutgers University 1958–1972. Mason Gross Art Galleries, Rutgers, and Mead Art Gallery, Amherst, 2003.

- Hendricks, Jon, ed. Fluxus, etc.: The Gilbert and Lila Silverman Collection. Bloomfield Hills, Michigan: Cranbrook Museum of Art, 1982.

- Hendricks, Jon. Fluxus Codex. New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1988.

- Higgins, Hannah. Fluxus Experience. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2002.

- Janssen, Ruud. Mail-Interviews Part 1 Interviews with Mail-Art and Fluxus Artists. Breda: TAM-Publications, Netherlands 2008.

- Kellein, Thomas. Fluxus. London and New York: Thames & Hudson, 1995.

- Milman, Estera, ed. "Fluxus: A Conceptual Country", Visible Language [Special Issue], vol. 26, nos. 1/2, Providence: Rhode Island School of Design, 1992.

- Fluxus y Di Maggio. Museo Vostell Malpartida, 1998, ISBN 84-7671-446-7.

- Moren, Lisa. Intermedia. Baltimore, Maryland: University of Maryland, Baltimore County, 2003.

- Paull, Silke, and Hervé Würz, eds. "How We Met or a Microdemystification". AQ 16 [Special Issue], (1977)

- Saper, Craig J. Networked Art. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2001.

- Schmidt-Burkhardt, Astrit. Maciunas' Learning Machines: From Art History to a Chronology of Fluxus, with a foreword by Jon Hendricks. Second, revised and enlarged edition, Vienna and New York: Springer, 2011. ISBN 978-3-7091-0479-8.

- Smith, Owen F. Fluxus: The History of an Attitude. San Diego, CA: San Diego State University Press, 1998.

- Nie wieder störungsfrei! Aachen Avantgarde seit 1964, Kerber Verlag, 2011, ISBN 978-3-86678-602-8.

- Fluxus at 50. Stefan Fricke, Alexander Klar, Sarah Maske, Kerber Verlag, 2012, ISBN 978-3-86678-700-1.

- Fluxus! 50 Jahre Fluxus. Werner Esser, Steffen Engle, Staatsgalerie Stuttgart, 2012. ISBN 978-3-86442-032-0.

- Stegmann, Petra, ed. 'The lunatics are on the loose…' European Fluxus festivals 1962–1977. Down with art! Berlin 2012. ISBN 978-3-9815579-0-9.

- Stegmann, Petra, ed. Fluxus East. Fluxus-Netzwerke in Mittelosteuropa. Fluxus Networks in Central Eastern Europe. Künstlerhaus Bethanien, Berlin 2007. ISBN 978-3932754876.

- Würz, Fleurice Fluxus Nice. Saarbrücken (Germany): AQ-Verlag, 2011. ISBN 978-3-922441-11-3.

- Zanichelli, Elena (2012). Women in Fluxus & Other Experimental Tales: Eventi Partiture Performance.

- Beuys Brock Vostell. Aktion Demonstration Partizipation 1949–1983. ZKM – Zentrum für Kunst und Medientechnologie, Hatje Cantz, Karlsruhe, 2014, ISBN 978-3-7757-3864-4.

Notes

[edit]- ^ Nationalencyclopedin (Swedish National Encyclopedia). 2016. "Fluxus". Accessible at: http://www.ne.se/uppslagsverk/encyclopedi/lång/fluxus Archived 23 April 2021 at the Wayback Machine Accessed September 11, 2016.

- ^ Wainwright, Lisa S. 2016. "Fluxus." Britannica Academic (Encyclopædia Britannica Online).

- ^ Higgins, Dick. 1966. "Intermedia." Something Else Newsletter. vol. 1, no. 1, February, pp. 1–3.

- ^ Higgins, Dick. 2001. "Intermedia" Multimedia: From Wagner to Virtual Reality. Randall Packer and Ken Jordan, eds. New York: W. W. Norton, pp. 27–32.

- ^ Higgins, Dick. 1984. Horizons: The Poetics and Theory of the Intermedia. Carbondale and Edwardsville: Southern Illinois University Press

- ^ Hannah B. Higgins, "The Computational Word Works of Eric Andersen and Dick Higgins", Mainframe Experimentalism: Early Digital Computing in the Experimental Arts, Hannah Higgins & Douglas Kahn, eds., pp. 271–281

- ^ Flynt, Henry. 1961. "Concept Art: Innperseqs." Reprinted in 1963: An Anthology. La Monte Young, ed. New York: Jackson Mac Low and La Monte Young, np.

- ^ Flynt, Henry. 1963. "Essay: Concept Art: Provisional Version." An Anthology. La Monte Young, ed. New York: Jackson Mac Low and La Monte Young, np.

- ^ Paik, Nam June. 1993. Nam June Paik: eine Data Base. La Biennale di Venezia. XLV Esposizione lnternazionale D'Arte, June 13 – October 10, 1993. Klaus Bußmann and Florian Matzner, eds. Venice and Berlin: Biennale di Venezia and Edition Cantz.

- ^ Hanhardt, John and Ken Hakuta. 2012. Nam June Paik: Global Visionary. London and Washington, D.C.: D. Giles, Ltd., in association with the Smithsonian American Art Museum.

- ^ Fundacio Joan Miro. 1979. Vostell. Environments Pintura Happenings Dibuixos Video de 1958 a 1978. Barcelona: Fundacio Joan Miro.

- ^ a b Ruhé, Harry. 1979. Fluxus, the Most Radical and Experimental Art Movement of the Sixties Amsterdam: Editions Galerie A.

- ^ Ruhé, Harry. 1999. "Introduction." 25 Fluxus Stories Amsterdam: Tuja Books, p. 4.

- ^ "Fluxus Movement, Artists and Major Works". Archived from the original on 19 October 2015. Retrieved 6 October 2015.

- ^ Armstrong, Elizabeth, ed. (1993). "The Occasion of the Exhibition". In the Spirit of Fluxus. Minneapolis: Walker Art Center. p. 24. ISBN 9780935640403.

- ^ Zurbrugg, Nicholas. 1990. "A Spirit of Large Goals." – Dada and Fluxus at Two Speeds. Fluxus! Nicholas Zurbrugg, Francesco Conz, and Nicholas Tsoutas, eds. Brisbane, Australia: Institute of Modern Art, p. 29.

- ^ Higgins, Dick. 1992. "Fluxus: Theory and Reception." Lund Art Press, vol II, no. 2, pp. 25–46.

- ^ Higgins, Dick. 1998. "Fluxus: Theory and Reception." The Fluxus Reader, Ken Friedman, ed. Chichester, West Sussex: Wiley Academy Editions, pp. 218–236.

- ^ Friedman, Ken. 2011. "Fluxus: A Laboratory of Ideas." Fluxus and the Essential Qualities of Life. Jacquelynne Baas, editor. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, p. 35.

- ^ Friedman, Ken. 2012. "Freedom? Nothingness? Time? Fluxus and the Laboratory of Ideas." Theory, Culture, and Society, vol. 29, no. 7/8, December, pp. 372–398. doi:10.1177/0263276412465440 Friedman, Ken (December 2012). "Freedom? Nothingness? Time? Fluxus and the Laboratory of Ideas - Ken Friedman, 2012". Theory, Culture & Society. 29 (7–8): 372–398. doi:10.1177/0263276412465440. S2CID 144894255. Archived from the original on 23 April 2021. Retrieved 23 April 2021.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ Maciunas himself joined the class in 1959–60, and was taught by Maxfield

- ^ Brecht & Robinson 2005, p. 28.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Michael Corris, MoMA, Grove Art Online, Oxford University Press, 2009". Archived from the original on 8 May 2015. Retrieved 12 June 2012.

- ^ Motherwell, Robert and Jean Arp (1989). The Dada Painters And Poets: An Anthology. Cambridge, Mass: Belknap Press Of Harvard University Press.

- ^ "Anti-art, Art that challenges the existing accepted definitions of art, Tate". Archived from the original on 5 April 2017. Retrieved 7 October 2015.

- ^ Cotter, Holland (6 July 2006). "Dada's Women, Ahead of Their Time". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 4 January 2017. Retrieved 17 May 2022.

- ^ Hapgood, Susan and Rittner, Jennifer. "Neo-Dada: Redefining Art, 1958–1962", Performing Arts Journal, vol. 17, no. 1 (January 1995), pp. 63–70.

- ^ "Performances at Yoko Ono's Chambers Street Loft". Archived from the original on 10 April 2016. Retrieved 2 July 2012.

- ^ "Tate, Nam June Paik, Fluxus, Performance, Participation". Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 4 July 2012.

- ^ 1986 interview on YouTube, Dick Higgins on Fluxus "Dick Higgins on FLUXUS - YouTube". YouTube. 15 March 2010. Archived from the original on 23 March 2017. Retrieved 27 November 2016.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ Amongst the earliest pieces that would later be published by Fluxus were Brecht's event scores, the earliest of which dated from around 1958/9, and works such as Valoche, which had originally been exhibited in Brecht's solo show 'Toward's Events' at 1959.

- ^ Colby Chamberlain, Fluxus Administration: George Maciunas and the Art of Paperwork, University of Chicago Press, 2024, p. 4

- ^ "Chamberlain, Colby. "Design in Flux" Art In America. 1 October 2014". Archived from the original on 8 July 2015. Retrieved 7 July 2015.

- ^ Hendricks 1988, p. 22.

- ^ Colby Chamberlain, Fluxus Administration: George Maciunas and the Art of Paperwork, University of Chicago Press, 2024, p. 4

- ^ Fluxus Manifesto, 1963, by George Maciunas

- ^ Hendricks 1988, p. 91.

- ^ Maciunas, Fluxus Prospectus, quoted in Hendricks 1988, p. 23

- ^ Raoul Hausmann, quoted in Maciunas & Ay-O 1998, p. 40. Letter dated 4 November 1962, according to Kellein 2007, n. 47, p. 65

- ^ The lecture was actually given in German by Artus C Caspari

- ^ a b Kellein 2007, p. 62

- ^ Marcus Boon Archived 2 November 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Die Irren sind los" quoted in Kellein 2007, p. 65

- ^ George Maciunas, letter to La Monte Young, 1962, quoted in Maciunas & Ay-O 1998, p. 53

- ^ Price listed in the Fluxus Preview Review, July 1963, quoted in Hendricks 1988, p. 217

- ^ Maciunas, letter to Emmett Williams, quoted in Maciunas & Ay-O 1998, p. 106

- ^ Hendricks 1988, p. 24.

- ^ Kellein 2007, p. 69.

- ^ This was to go down to 50/50 within a yearKellein 2007, p. 88

- ^ Maciunas sent out letters to 20 international artists between late 62 and early 63, demanding each artist relinquish any publishing rights and have Fluxus as sole and exclusive publisher. Maciunas likened his agreement to Cage's arrangement with Peters Editions. Only two artists—Henry Flynt and Thomas Schmit signed up. Cage was not asked, due at least on Maciunas' side, to the aforesaid contract with editions peters. Kellein 2007, pp. 69–71

- ^ George Brecht, "An Interview with Robin Page for Carla Liss", In Art And Artists, London October 1972, pp. 30–31 reprinted in Maciunas & Ay-O 1998, pp. 109–110

- ^ Cotter, Holland (24 May 1996). "Art in Review: The man who organized Fluxus". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 27 June 2017. Retrieved 17 May 2022.

- ^ Maciunas & Ay-O 1998, p. 340.

- ^ a b Kellein 2007, p. 93

- ^ Brecht & Robinson 2005, p. 118.

- ^ Kellein 2007, p. 109.

- ^ At the time, a member of the leftist set WWP.Maciunas & Ay-O 1998, p. 108

- ^ Bloch, Mark. "On Originale.", from Bloch, Mark, editor Archived 24 September 2015 at the Wayback Machine. "Robert Delford Brown: Meat, Maps and Militant Metaphysics", Cameron Museum of Art, Wilmington, North Carolina, 2008.

- ^ Kellein 2007, p. 98.

- ^ "Picket Stockhausen Concert!", Flynt and Maciunas flyer, 1964. Reproduced[full citation needed]

- ^ "A film of the event, UbuWeb". Archived from the original on 10 February 2012. Retrieved 15 June 2012.

- ^ Dick Higgins, "A Child's History of Fluxus", 1979. Archived 22 June 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Kellein 2007, n. 104, p. 98.

- ^ "Charlotte Moorman and Nam June Paik "The Originale"". YouTube. Archived from the original on 31 December 2018. Retrieved 27 November 2016.

- ^ "Stewart Home, The Assault on Culture, The origins of Fluxus and the movement in its 'heroic' period, Chapter 9". Archived from the original on 2 June 2009. Retrieved 16 June 2012.

- ^ Jackson Mac Low quoted in Maciunas & Ay-O 1998, pp. 94–95

- ^ Kellein 2007, p. 101.

- ^ Kellein 2007, p. 102.

- ^ Weisman, S. (2011). The mind music of Yoko Ono: Screams and silences at the intersection of the real and the imagined (195-196)(Order No. 3458632). Available from ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global. (872186218).

- ^ Laynor, Gregory (2016). The Making of Intermedia: John Cage to Yoko Ono, 1952 to 1972. Vol. 78-03A. University of Washington. English, Brian Reed. Ann Arbor. pp. (94). ISBN 978-1-339-94191-2. OCLC 1257952914.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Sallabedra, M. (2012). Like an elephant's tail: Process and instruction in the work of Michael Rakowitz, Rirkrit Tiravanija and Yoko Ono (7) (9-20) (Order No. 1514168). Available from ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global. (1026566248).

- ^ Ono, Y. (1964). Grapefruit. Wunternaum Press.

- ^ Interview with Joe Jones by Nakagawa Shin Archived 3 January 2017 at the Wayback Machine (1992)

- ^ Smith 1998, pp. 206–209.

- ^ "Joint Yoko Ono, John Lennon, & Fluxgroup Project / Press Release -- April 1, 1970". Archived from the original on 21 January 2021. Retrieved 15 January 2021.

- ^ "Fluxkit, MoMA". Archived from the original on 17 May 2012. Retrieved 4 July 2012.

- ^ Hendricks 1988, p. 76.

- ^ a b "MoMA, Interactive exhibitions". Archived from the original on 4 September 2012. Retrieved 28 June 2012.

- ^ Hendricks 1988, p. 124.

- ^ Yoko Ono, for instance, has claimed authorship of Mieko Shiomi's Disappearing Music For Face (aka Smile) for instance.

- ^ Hendricks 1988, p. 290.

- ^ Hendricks 1988, p. 291.

- ^ "All contributors will receive a box in return..." Hendricks 1988, p. 542

- ^ "Fluxus East: Fluxus Networks in Central Eastern Europe". Archived 4 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Marter, Joan M. and Anderson, Simon. Off Limits: Rutgers University and the Avant-garde, 1957–1963. Newark Museum. Newark, New Jersey

- ^ Hendricks, Geoffrey, editor. Critical Mass: Happenings, Fluxus, Performance, Intermedia, and Rutgers. Mead Art Museum, Amherst, Massachusetts

- ^ Marcus, Griel. Real Life Rock: The Complete Top Ten Columns, 1986–2014. Yale University Press, New Haven, Connecticut p. 114.

- ^ Bloch, Mark (July 2023). "A New Book and a Museum Show for Sari Dienes". Whitehot Magazine. Retrieved 8 September 2023.

- ^ a b O'Dell 1997

- ^ Yoshimoto, Midori; Knowles, Alison; Schneemann, Carolee; Seagull, Sara; Moore, Barbara; Shiovitz, Brynn Wein; Yoshimoto, Midori; Pittman, Alex (November 2009). "An evening with Fluxus women: a roundtable discussion". Women & Performance: A Journal of Feminist Theory. 19 (3): 369–389. doi:10.1080/07407700903399524. S2CID 194022721.

- ^ Terpenkas, Andrea (June 2017). "Fluxus, Feminism, and the 1960's". Western Tribularies. 4.

- ^ a b "The History of Artists and Art Production in SoHo, Danielle". 11 October 2011. Archived from the original on 9 February 2013. Retrieved 2 July 2012.

- ^ Harren, Natilee. "La cédille qui ne finit pas: Robert Filliou, George Brecht, and Fluxus in Villefranche". Getty Research Journal, no. 4 (2012), pp. 127–143.

- ^ "Fluxkit documenting the project". Archived from the original on 6 October 2014. Retrieved 4 July 2012.

- ^ Kellein 2007, p. 131.

- ^ Kellein 2007, p. 132.

- ^ Kellein 2007, p. 147.

- ^ DiTolla, Racy (2015). "Fluxus Movement, Artists and Major Works". The Art Story. Archived from the original on 19 October 2015. Retrieved 6 October 2015.

- ^ Interview with Larry Miller, 1978, referenced in Maciunas & Ay-O 1998, p. 114

- ^ "Marriage of George and Billy Maciunas". YouTube. 18 June 2011. Archived from the original on 7 March 2016. Retrieved 9 September 2014.

- ^ According to Hutching, quoted in Maciunas & Ay-O 1998, p. 280. Maciunas was a transvestite and masochist.

- ^ Johnson, Ken (23 September 2011). "Liberating Viewers, and the World, With Silliness". The New York Times (exhibition review). Archived from the original on 17 April 2017. Retrieved 17 May 2022.

- ^ "Fluxus at NYU". Archived from the original on 23 December 2011. Retrieved 15 December 2011.

- ^ Phillpot, Clive; Hendricks, Jon (1988). Fluxus : selections from the Gilbert and Lila Silverman Collection. Museum of Modern Art. p. 15. ISBN 0870703110.

- ^ "Robert Pincus-Witten on Fluxus, and Jon Hendricks's Codex". Archived from the original on 16 April 2012. Retrieved 15 December 2011.

- ^ MoMA exhibitions, October 2009 – August 2010 Archived 14 September 2010 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 5 September 2010

- ^ "Always in Flux, Mostly in Fun" by David Bratman, sfcv.org Archived 10 August 2014 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 1 August 2014

- ^ "Something Else: A Fluxus Semicentenary". Other Minds Archives. Retrieved 15 February 2024.

- ^ "Interview with Hannah Higgins". Archived from the original on 5 February 2012. Retrieved 16 December 2011.

- ^ "Bloch, Mark. "The Boat Book: Alison Knowles"". Archived from the original on 3 July 2017. Retrieved 7 July 2015.

- ^ "Drinkall, Jacquelene. "Human Telepathic Collaborations from Fluxus to Now"" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 July 2015. Retrieved 7 July 2015.

- ^ Barone, Joshua (11 November 2018). "What Happens When Fluxus Enters the Concert Hall?". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 17 November 2018. Retrieved 17 November 2018.

- ^ Galliano, Luciana (Summer 2006). "Toshi Ichiyanagi, Japanese Composer and "Fluxus"". Perspectives of New Music. 44 (2): 250–261. doi:10.1353/pnm.2006.0012. JSTOR 25164637. S2CID 258131560.

- ^ Robert Filliou on Fluxus and art Archived 19 September 2011 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 5 September 2010

- ^ Ken Friedman, 40 Years of Fluxus Archived 11 February 2010 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 5 September 2010

- ^ a b Maciunas on Fluxus Archived 10 February 2010 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 5 September 2010

- ^ Fluxus and Happening, the Something Else Press Archived 3 February 2011 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 5 September 2010

- ^ UBUWeb Archived 14 September 2010 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 5 September 2010

- ^ Bloch, Mark (February 2019). "Intermedia, Fluxus And The Something Else Press: Selected Writings By Dick Higgins". Whitehot Magazine. Retrieved 8 September 2023.

- ^ Kellein & Hendricks 1995, p. 11.

- ^ Kotz, Liz (Spring 2001). "Post-Cagean aesthetics and the 'event' score". October. 95 (95): 55–89. JSTOR 779200.

- ^ Dezeuze, Anna (January 2002). "Origins of the Fluxus score: from indeterminacy to the 'do-it-yourself' artwork". Performance Research. 7 (3): 78–94. doi:10.1080/13528165.2002.10871876. S2CID 191234739.

- ^ Robinson, Julia (Winter 2009). "Abstraction to model: George Brecht's events and the conceptual turn in art of the 1960s". October. 127: 77–108. doi:10.1162/octo.2009.127.1.77. JSTOR 40368554. S2CID 57562781.

- ^ Bloch, Mark (February 2023). "Book Review: A Something Else Reader, Edited by Dick Higgins". Whitehot Magazine. Retrieved 8 September 2023.

- ^ a b Brill, Dorothée (2010). Shock and the Senseless in Dada and Fluxus. University Press of New England. p. 131. ISBN 9781584659174. Archived from the original on 23 April 2021. Retrieved 25 October 2020.

- ^ Toop, David (5 May 2016). Into the Maelstrom: Music, Improvisation and the Dream of Freedom: Before 1970. Bloomsbury Publishing USA. p. 294. ISBN 9781441102775. Archived from the original on 23 April 2021. Retrieved 25 October 2020.

- ^ a b c Rush 2005, p. 24

- ^ On George Brecht, Robert Filliou and others Archived 14 November 2010 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 5 September 2010

- ^ a b Rush 2005, p. 25

- ^ a b O'neill, Rosemary. In the Spirit of Fluxus. Art Journal 53.1 (1994): 90–93. Web.

- ^ O'Dell 1997.

- ^ Fluxus, More Flux Than History. Art-Press 391 (2012): 65–69. Art Source. Web. 6 October 2015.

- ^ a b O'Dell 1997, p. 43

- ^ Oren 1993, p. 8.

- ^ Baas, Jacquelynn, et al. Fluxus and the Essential Questions of Life, pp 80,86. Chicago and Hanover, NH: University of Chicago Press and Hood Museum of Art, 2011.

- ^ "Tate Archive and Public Records Catalogue". Archived from the original on 23 April 2021. Retrieved 8 July 2015.

- ^ "Fondation du Doute". Archived from the original on 24 October 2016. Retrieved 14 October 2016.

- ^ "Museo Vostell Malpartida". Archived from the original on 20 July 2020. Retrieved 23 April 2021.

- ^ "Museum Fluxus+ Potsdam, Germany". Archived from the original on 28 December 2017. Retrieved 3 September 2005.

- ^ Getty Research Institute Selected Special Collections Finding Aids. Jean Brown papers, 1916–1995, bulk 1958–1985.. Retrieved 28 August 2008.

- ^ "The Endless Story of FLUXUS". Archived from the original on 24 February 2021. Retrieved 23 April 2021.

Sources

[edit]- Hendricks, Jon (1988). Fluxus Codex. New York: Harry N. Abrams. ISBN 9780810909205.

- Kellein, Thomas; Hendricks, Jon (1995). Fluxus. London: Thames & Hudson.

- Kellein, Thomas (2007). George Maciunas: The Dream of Fluxus. New York: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 9780500976654.

- Maciunas, George; Ay-O (1998). Emmett Williams; Ann Noël (eds.). Mr. Fluxus – A Collective Portrait of George Maciunas, 1931–1978. London: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 9780500974612. OCLC 38974950.

- O'Dell, Kathy (Spring 1997). "Fluxus Feminus". TDR: The Drama Review. 41 (1): 43–60. doi:10.2307/1146571. JSTOR 1146571.

- Oren, Michel (1993). "Anti-Art as the End of Cultural History". Performing Arts Journal. 15 (2): 1–30. doi:10.2307/3245708. JSTOR 3245708. S2CID 195053017.

- Brecht, George; Robinson, Julia (2005). George Brecht: Events – Eine Heterospektive (in German). Cologne: Museum Ludwig and Buchhandlung Walther König.

- Rush, Michael (2005). New Media in Art. London: Thames & Hudson.

- Smith, Owen (1998). Fluxus: The History of an Attitude. San Diego: San Diego State University Press.

External links

[edit]- Links at Ubuweb:

- Interview with Ken Friedman

- European Fluxus Festivals 1962–1977

- John Cage on I've Got A Secret performing Water Walk, January 1960, from the same era as his teaching classes at the New School

- MOMA online archive of Fluxus 1, Fluxkit and Flux Year Box 2

- Museum Fluxus+ Potsdam, Germany

- Museo Vostell Malpartida, Cáceres, Spain.

- Subjugated Knowledges exhibition catalogue

- The Copenhagen Fluxus Archive Archived 10 August 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- Dick Higgins collection at the University of Maryland, Baltimore County

- Fondazione Bonotto, Fluxus works collection

- Fluxus Digital Collection, University of Iowa

- Fluxus Comes Alive - interactive Fluxus guide

- Fluxus discography at Discogs