Weimar Constitution

| Constitution of the German Reich | |

|---|---|

The Weimar Constitution in booklet form. Article 148 of the Constitution required that all school students receive a copy of the Constitution at the time of their graduation. | |

| Overview | |

| Original title | Die Verfassung des Deutschen Reichs |

| Jurisdiction | Weimar Republic (1919–1933) Nazi Germany (1933–1945, de jure only) Allied-occupied Germany (1945–1949, de jure only) |

| Ratified | 11 August 1919 |

| Date effective | 14 August 1919 |

| System | Federal semi-presidential republic (1919–1930) de jure till 1945 Federal authoritarian presidential republic under a Parliamentary System (1930–1933) Unitary Nazi one-party fascist totalitarian dictatorship (1933–1945) de facto |

| Head of state | President (1919–1934) Führer (1934–1945) |

| Chambers | Upper house: Reichsrat (until 1934) Lower house: Reichstag |

| Executive | Chancellor |

| Judiciary | Reichsgericht |

| Federalism | Yes (disregarded in 1933) |

| Repealed | |

| Supersedes | Constitution of the German Empire |

| Full text | |

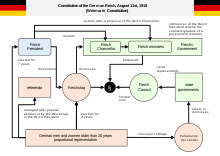

The Constitution of the German Reich (German: Die Verfassung des Deutschen Reichs), usually known as the Weimar Constitution (Weimarer Verfassung), was the constitution that governed Germany during the Weimar Republic era (1919–1933). The constitution created a federal semi-presidential republic with a parliament whose lower house, the Reichstag, was elected by universal suffrage using proportional representation. The appointed upper house, the Reichsrat, represented the interests of the federal states. The president of Germany had supreme command over the military, extensive emergency powers, and appointed and removed the chancellor, who was responsible to the Reichstag. The constitution included a significant number of civic rights such as freedom of speech and habeas corpus. It guaranteed freedom of religion and did not permit the establishment of a state church.

The constitution contained a number of weaknesses which, under the difficult conditions of the interwar period, failed to prevent Adolf Hitler from setting up a Nazi dictatorship using the constitution as a cover of legitimacy. Although it was de facto repealed by the Enabling Act of 1933, the constitution remained technically in effect throughout the Nazi era from 1933 to 1945 and also during the Allied occupation of Germany from 1945 to 1949. It was then replaced by the Basic Law for the Federal Republic of Germany (West Germany until 1990, then reunited Germany) and the Constitution of the German Democratic Republic (East Germany).

The constitution's title was the same as the Constitution of the German Empire that preceded it. The German state's official name was German Reich (Deutsches Reich) until 1949.

Origin

[edit]After the end of World War I, the government of Imperial Germany collapsed during the early days of the German revolution of 1918–1919. In the following months, the far left parties that fought to establish a soviet republic were defeated by those of the moderate left that wanted a parliamentary republic. The victorious parties, led by Friedrich Ebert of the Social Democrats (SPD), scheduled an election on 19 January 1919 – in which women for the first time had equal voting rights with men[1] – for a national assembly that was to act as Germany's interim parliament and draft a new constitution.[2] Because conditions in Berlin were still unsettled, the delegates met at Weimar. Ebert wanted the victorious Allies to be reminded of Weimar Classicism, which included the writers Goethe and Schiller, while they were deliberating the terms of the Versailles Treaty.[3]

The initial draft of the constitution was written by the lawyer and liberal politician Hugo Preuss, who headed the Ministry of the Interior.[4] He based his draft in large part on the Frankfurt Constitution of 1849 which was written after the German revolutions of 1848–1849 and intended for a unified Germany that did not come to pass at the time. He was influenced as well by Robert Redslob's theory of parliamentarianism, which called for a balance between the executive and legislative branches under either a monarch or the people as sovereign.[5]

During July 1919, the National Assembly moved quickly through the draft constitution with most debates concluded within a single session and without public discussion of the issues.[6] On 31 July the assembly adopted the new constitution by a vote of 262 to 75 with 1 abstention.[7] Friedrich Ebert, the first president of Germany, signed the Weimar Constitution on 11 August 1919, and it became effective on the 14th. A federal election was held on 6 June 1920 for the new Reichstag.[8]

Provisions and organization

[edit]

The Weimar Constitution was divided into two main parts or chapters. They in turn were divided into seven and five sections respectively. In all, there were 181 articles in the constitution.

Some of the more noteworthy provisions are described below, including those provisions which proved significant in the demise of the Weimar Republic and the rise of Nazi Germany.

The preamble to the Constitution reads:

The German people united in every respect and inspired by the determination to restore and confirm the Reich in liberty and justice, to serve peace at home and peace abroad, and to further social progress, has given itself this constitution.

Chapter I: Organization and functions of the Reich

[edit]The first part of the constitution specified the organization of the various parts of the federal government.

Section 1: The Reich and the states

[edit]Section 1 consisted of Articles 1 to 19 and established the German Reich as a republic whose power derived from the people. The Reich was defined as the region encompassed by the German states; other regions could be incorporated into the Reich based on popular self-determination and corresponding Reich legislation. (Germany received the terms of the Treaty of Versailles, which reduced its land area and population by 13% and 12% respectively, on 7 May 1919, while the constitution was being debated in the National Assembly.)[9]

Section 1 also established that generally recognized principles of international law were binding on Germany and gave the Reich government exclusive jurisdiction of:

- foreign relations

- colonies

- citizenship, freedom of movement, immigration, emigration and extradition

- national defence

- currency

- customs

- mail, telegraph and telephone services

Articles 7 through 11 listed many more areas in which the Reich was allowed to either legislate or prescribe fundamental principles, notably "taxation and other revenues in so far as they are claimed in whole or in part for its purposes".

With the exceptions of the subjects for which the Reich government had exclusive jurisdiction, the states could pass legislation for their respective territories as they saw fit. Reich law superseded or nullified state law in the event of a conflict. Adjudication of conflicts between a state and the Reich government fell under the jurisdiction of the Supreme Judicial Court.

States were required to have a republican constitution and its authorities to enforce Reich law. Each state parliament (Landtag) was to be elected by equal, secret, direct and universal (both men and women) ballot according to the principles of proportional representation. Each state government (the "state ministry") could serve only so long as it had the confidence of the respective state parliament.

Section 2: The Reichstag and the Reich government

[edit]Articles 20 to 40 described the national parliament, the Reichstag, which was seated in the capital, Berlin. The Reichstag was composed of representatives elected by the German people by an equal and secret ballot open to all Germans over 20 years of age. Proportional representation principles governed Reichstag elections.

Members of the Reichstag represented the entire nation and were bound only to their own conscience. Members served for four years. The Reichstag could be dissolved by the Reich president, and new elections had to be held not more than 60 days after the date of dissolution.

Members of the Reichstag and of the state parliaments were immune from arrest or investigation of a criminal offense except with the approval of the legislative body to which the person belonged. The same approval was required for any other restriction on personal freedom which might harm the member's ability to fulfil his duties.

Section 3: The president of the Reich and the national ministry

[edit]

Articles 41 to 59 describe the duties of the president, including the qualifications for the office. They also explain his relationship to the national ministry (cabinet) and the chancellor.

The president served a term of seven years and could be re-elected once. He could be removed from office by referendum following a vote of two-thirds of the Reichstag. Rejection of the measure by the voters would act as a re-election of the president and cause the Reichstag to be dissolved. If a state failed to fulfil its obligations under the constitution or Reich law, the president could use armed force to compel the state to do so under a Reichsexekution. Article 48 gave the president the power to take measures – including the use of armed force and/or the suspension of civil rights – to restore law and order in the event of a serious threat to public safety or security. Since Article 50 required all of the president's decrees to be counter-signed by the chancellor or "competent national minister", use of Article 48 required agreement between president and chancellor. The president was also required to inform the Reichstag of the use of such measures, and the Reichstag could nullify the decree. In 1933 President Paul von Hindenburg and Chancellor Adolf Hitler, using Article 48 as the basis for the Reichstag Fire Decree, legally swept away most of the key the civil liberties granted in the Weimar Constitution and thereby facilitated the establishment of a dictatorship.[10]

The president had supreme command over the military and appointed and removed the chancellor and, on the chancellor's recommendation, the members of the cabinet. The chancellor determined the political guidelines of his government and was responsible to the Reichstag. The chancellor and ministers were compelled to resign in the event the Reichstag passed a vote of no confidence. It was not, however, a constructive vote of no confidence, which requires that there be a positive majority for a prospective successor before confidence can be withdrawn. Under the Weimar Constitution, the vote of no confidence often resulted in difficulty forming new coalitions and a degree of parliamentary instability that in the end was fatal to the Republic.[11][12]

The government (cabinet) formulated decisions by majority vote; in the case of a tie, the president's vote was decisive. The Reichstag could accuse the president, chancellor, or any minister of willful violation of the constitution or Reich law, with the case to be tried in the Supreme Judicial Court.

Section 4: The Reichsrat

[edit]Section 4 consisted of Articles 60 to 67 and established the Reichsrat (State Council). The Reichsrat was the means by which the states participated in legislation at the national level. The number of members was based on the states' populations, with the restriction that no state could have more than two-fifths of the total – a provision that limited only Prussia's influence[13][14] since it had three-fifths of Germany's population.[15] Members of the Reichsrat were required to be members the state ministries, with the exception again of Prussia, half of whose members had to be appointed from among the Prussian provincial administrative authorities. Although not specified in the constitution, members – except for the Prussians who were provincial representatives – were considered to be bound by the instructions of their respective state governments.[16] Government ministers were required to inform the Reichsrat of proposed legislation or administrative regulations to permit the Reichsrat to voice objections.

Article 61 stated that "German Austria, after union with the German Reich, shall be represented in the Reichsrat by votes corresponding in number to its population". The Republic of German-Austria had been established after the dissolution of Austria-Hungary from the predominantly German-speaking regions of the former empire. Hugo Preuss publicly criticised the Triple Entente's decision in the Treaty of Versailles to prohibit the unification of "Greater Germany", saying that it was a contradiction of the Wilsonian principle of the self-determination of peoples.[17]

Section 5: National legislation

[edit]Articles 68 to 77 specified how legislation was to be passed into law. Laws could be proposed by a member of the Reichstag or by the Reich government and were passed on the majority vote of the Reichstag. Proposed legislation had to be presented to the Reichsrat, and the latter body's objections were required to be presented to the Reichstag.

The Reich president had the power to decree that a proposed law be presented to the voters as a referendum before taking effect.

The Reichsrat was entitled to object to laws passed by the Reichstag. If the objection could not be resolved, the Reich president at his discretion could call for a referendum or let the proposed law die. If the Reichstag voted to overrule the Reichsrat's objection by a two-thirds majority, the Reich president was obligated to either proclaim the law into force or to call for a referendum.

Constitutional amendments were proposed as ordinary legislation, but for such an amendment to take effect, it was required that two-thirds or more of the Reichstag members be present and that at least two-thirds of the members present vote in favor of the legislation.

The Reich government had the authority to establish administrative regulations unless Reich law specified otherwise.

Section 6: National administration

[edit]Articles 78 to 101 described the methods by which the Reich government administered the constitution and laws, particularly in the areas where the Reich government had exclusive jurisdiction – foreign relations, colonial affairs, defence, taxation and customs, merchant shipping and waterways, railroads and so forth.

Section 7: Administration of justice

[edit]Articles 102 to 108 established the justice system of the Weimar Republic. The principal provision mandated judicial independence – judges were responsible only to the law. Extraordinary courts were prohibited and military courts allowed only during wartime and aboard warships.

The section required that laws be promulgated to establish a Supreme Judicial Court and administrative courts to adjudicate disputes between citizens and administrative offices of the state. The law to set up the Supreme Judicial Court (Staatsgerichtshof für das Deutsche Reich) was passed in July 1921.[18]

Chapter II: Fundamental rights and duties of Germans

[edit]The second part of the Weimar Constitution laid out the basic rights and obligations of Germans. The German Civil Code of 1900, which included sections on personal rights and domestic relations, remained in effect.[19]

The constitution guaranteed individual rights such as freedom of speech and assembly to each citizen. They were based on the provisions of the earlier constitution of 1848.[20]

Section 1: The individual

[edit]Articles 109 to 118 set forth the individual rights of Germans, the principal tenet being that every German was equal before the law. Men and women had "in principle" the same civil rights and duties. Privileges based on birth or rank – that is, the German nobility – were abolished. Official recognition of the titles of nobility ceased, except as a part of a person's name, and creation of noble titles was discontinued.

A citizen of any of the German states was likewise a citizen of Germany. Germans had the right of mobility and residence, and the right to acquire property and pursue a trade. They had the right to emigrate and to government protection against foreign authorities.

The "traditional development" (volkstümliche Entwicklung) of foreign language communities in Germany was protected, including the right to use their native language in education, administration, and the judicial system.

Other specific articles stated that:

- The rights of the individual are inviolable. Individual liberties may be limited or deprived only on the basis of law. Persons have the right to be notified within a day of their arrest or detention as to the authority and reasons for their detention and be given the opportunity to object (Article 114).[†] This is equivalent to the principle of habeas corpus in the common law of England and elsewhere.

- A German's home is a sanctuary and is inviolable (Article 115).[†]

- Privacy of mail, telegraph and telephone are inviolable (Article 117).[†]

- Germans are entitled to free expression of opinion in word, writing, print, image, etc. This right cannot be obstructed due to employment, nor can exercise of the right create a disadvantage. Censorship is prohibited, except by law in the case of cinematography and obscene literature (Article 118).[†]

Section 2: Community life

[edit]Articles 119 to 134 guided Germans' interaction with the community and established, among other provisions, that:

- Marriage, based on the equality of the sexes, was put under the special protection of the state. Illegitimate children were granted equal rights.

- Germans had the right to assemble peacefully and unarmed without prior permission (Article 123).[†]

- Germans were entitled to form clubs or societies, which were permitted to acquire legal status. The status could not be denied because of the organization's political, socio-political or religious goals (Article 124).[†]

- Free and secret elections were guaranteed (Article 125).

- All citizens were eligible for public office, without discrimination, based on their abilities. Gender discrimination toward female civil servants was abolished (Article 128).

- Civil servants served the whole nation, not a specific party. They enjoyed freedom of political opinion (Article 130).

- Citizens could be required to provide services to the state and community, including compulsory military service under regulations set by law.

Section 3: Religion and religious communities

[edit]The religious rights of Germans were enumerated in Articles 135 to 141. Residents of Germany were granted freedom of belief and conscience. Free practice of religion was guaranteed and protected by the state. No state church was established.

The exercise of civil and civic rights and admission to state office were independent of one's religious beliefs. Public declaration of religious beliefs was not required, and no one was forced to join in a religious act or swear a religious oath.

Five articles from this section of the Constitution (Nos. 136–139 and 141) were incorporated into the Basic Law of the Federal Republic of Germany (passed in 1949)[21] and remain constitutional law in Germany today.

Section 4: Education and schools

[edit]Articles 142 to 150 guided the operation of educational institutions within the Reich. Public education was provided by state institutions and regulated by the government, with cooperation between federal, state and local authorities. Primary school was compulsory (eight years), with advanced schooling available to age 18 free of charge.

The constitution also provided for private schooling, which was likewise regulated by the government. In private schools operated by religious communities, religious instruction could take place in accordance with the religious community's principles.

Section 5: The economy

[edit]Constitutional provisions about economic affairs were given in Articles 151 to 165. One of the fundamental principles was that economic life should conform to the principles of justice, with the goal of achieving a dignified life for all and securing the economic freedom of the individual.

The Reich protected labor, intellectual creation, and the rights of authors, inventors, and artists. The right to form unions and to improve working conditions was guaranteed to every individual and to all occupations, and protection of the self-employed was established. Workers and employees were given the right to participate, on an equal footing with employers, in the regulation of wages and working conditions as well as in economic development.

The Reich reserved the right to "transfer to public ownership private economic enterprises suitable for socialization". It undertook to provide comprehensive insurance for health, maternity and old age. Workers were to be given legal representation on factory workers' councils.

Transition and final clauses

[edit]The final 16 articles (Articles 166 to 181) of the Weimar Constitution provided for the orderly transition to the new constitution and stipulated in some cases when the various provisions of the new constitution were to take effect. In cases where legislation had yet to be passed (such as the laws governing the new Supreme Judicial Court), the articles stipulated how the constitutional authority would be exercised in the interim by existing institutions. The section also stipulated that new bodies established by the constitution take the place of obsolete bodies (such as the National Assembly) where those bodies were referred to by name in old laws or decrees.

It was mandated that public servants and members of the armed forces take an oath on the constitution.

The Constitution of the German Empire dated 15 April 1871 was suspended, but other Reich laws and decrees that did not contradict the new constitution remained in force. Other official decrees based on previously valid law remained valid until superseded by law or decree.

The National Assembly was regarded as the Reichstag until the first Reichstag was elected and convened, and the Reich president elected by the National Assembly (Friedrich Ebert) was to serve until 30 June 1925.

Weaknesses

[edit]In his book The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich, historian William L. Shirer described the Weimar Constitution as "on paper, the most liberal and democratic document of its kind the twentieth century had ever seen ... full of ingenious and admirable devices which seemed to guarantee the working of an almost flawless democracy."[22] Yet the Weimar Constitution had serious problems, one of the most serious of which was its legitimacy in the eyes of the German people. Historian Hans-Ulrich Wehler argued that the manner in which Ebert received the "mantle of legitimacy" (the chancellorship) from Prince Max of Baden, the last chancellor of the Empire, resembled a coup and that the Council of the People's Deputies which Ebert led until the convening of the National Assembly functioned "by virtue of revolutionary law". In addition, there was no public debate on the decisions the National Assembly took on issues with serious long-term consequences, with the result that "the sovereign people once again proved to be a useful fiction for legitimacy".[23]

In the text itself, the extent of presidential powers proved to be deeply problematic. The governmental structure was a mix of presidential and parliamentary systems, with a strong president as a "replacement monarch" who was intended to be above political parties and a counterweight to the Reichstag and the potential for the "parliamentary absolutism" that Preuss feared.[24][25] The constitution allowed the president to dismiss the chancellor even if he retained the confidence of the Reichstag. Similarly, the president could appoint a chancellor who did not have the Reichstag's support. Article 48, the so-called emergency decree provision, gave the president broad powers to suspend civil liberties, with the checks and balances in it proving in practice to be insufficient. Article 48 also allowed the president to depose local governments, a power which was used four times and targeted only left-wing ministers (see Reichsexekution).[26][27] Although the original intent was that Article 48 would be used sparingly to restore constitutional order in the event of a national emergency, it was invoked 205 times before Adolf Hitler became chancellor.[28] It was thus no anomaly that he seized the opportunity to use its powers to begin solidifying his dictatorship just a month after his appointment (see following section).

The use of a proportional electoral system without thresholds to win representation has also been cited as a significant weakness. The system, intended to avoid the wasting of votes, allowed the rise of a multitude of parties which made it difficult for any of them to establish and maintain a workable parliamentary majority. This factionalism was one contributing factor in the frequent changes in government.[29] In the July 1932 Reichstag election, for example, there were 14 parties that gained enough votes to win at least one seat (out of a total of 62 parties that received votes). It was possible to win a seat in the chamber with as little as 0.1 percent of the vote. In the July 1932 election, for instance, the People's Justice Party, with just 40,800 votes out of over 37 million cast, picked up a seat.[30] The rise of the Nazis (NSDAP) to form the largest party in the 1932 election, however, can be attributed only to the sentiment of voters. Critics of electoral thresholds dispute the argument that the Nazis' token presence in the Reichstags of the 1920s significantly aided their rise to power and that the existence of thresholds in the Weimar Constitution would not in fact have hindered Hitler's ambitions – indeed, once the Nazis had passed the thresholds, their existence would have aided the Nazis by allowing them to marginalize smaller parties even more quickly. [citation needed]

In presidential elections, the Weimar Constitution stated only that the president would be "elected by the entire German people", with detailed specifications to come from a national law. The "Law on the Election of the Reich President of 4 May 1920" set up a two-round system in which the second round, if needed because no candidate won a majority of votes in the first, was not limited to the top two vote-getters but was won by whoever had the most votes out of all candidates choosing to run.[31] The second round of the 1925 German presidential election was thus not a contest between the DVP's Karl Jarres (1st place) and the SPD's Otto Braun (2nd place), who both belonged to parties which accepted the political system of the Weimar Republic, but was a three-person race between the Centre Party's Wilhelm Marx (3rd place in the first round; candidate of the Weimar Coalition), the Communist leader Ernst Thälmann (4th place in the first round), and Paul von Hindenburg, the commander of the Imperial German Army during World War I and candidate of the monarchist far-right, who won the election with 48% of the vote despite not having stood in the first round.[32]

In the early days of the German revolution, the moderate leadership of the Council of the People's Deputies decided that for the sake of stability it was better to keep the large bureaucratic machinery of the Empire than to attempt to replace thousands of experienced officials, the majority of whom remained loyal to the monarchy. When the Weimar Constitution was being written, the powerful German Civil Service Federation (Deutscher Beamtenbund) was able to exert pressure to add special protections for government officials in Articles 128 to 131, even though Preuss had had no intention of including such language. In addition to liberal provisions that granted freedom of political opinion, the articles guaranteed professional government officials life appointments and old age and survivors' benefits. This special inclusion in the constitution proved to be a considerable problem for the Republic in that it made it difficult for bureaucratic reforms to remove the many opponents of democracy in high-ranking positions, especially the judiciary.[33]

Even without these problems, the Weimar Constitution was established and in effect under very difficult social, political, and economic conditions. In his book The Coming of the Third Reich, historian Richard J. Evans argues that

all in all, Weimar's constitution was no worse than the constitutions of most other countries in the 1920s, and a good deal more democratic than many. Its more problematical provisions might not have mattered so much had the circumstances been different. But the fatal lack of legitimacy from which the Republic suffered magnified the constitution's faults many times over.[34]

Hitler's subversion of the Weimar Constitution

[edit]Less than a month after Adolf Hitler’s appointment as chancellor in 1933, the Reichstag Fire Decree invoked Article 48 of the Weimar Constitution, suspending several constitutional protections on civil rights. The articles affected were 114 (habeas corpus), 115 (inviolability of residence), 117 (correspondence privacy), 118 (freedom of expression/censorship), 123 (assembly), 124 (associations) and 153 (expropriation).[10]

The subsequent Enabling Act, passed by the Reichstag on 23 March 1933, stated that, in addition to the traditional method of the Reichstag passing legislation, the Reich government (the chancellor and cabinet) could also pass legislation. It further stated that the powers of the Reichstag, Reichsrat and Reich president were not affected. The normal legislative procedures outlined in Articles 68 to 77 of the constitution did not apply to legislation promulgated by the Reich government.[35]

The Enabling Act, which passed by a vote of 441 to 94, formally met the requirements for a constitutional amendment (two-thirds of the Reichstag's members were present, and two-thirds of the members present voted in favor of the measure) – but that was only after the 81 members of the Communist Party had been forcibly excluded. The Act did not explicitly amend the Weimar Constitution, but it did state that the procedure required for constitutional reform had been met. The constitution of 1919 was never formally repealed, but the Enabling Act meant that all its other provisions were a dead letter.[36]

Two of the penultimate acts Hitler took to consolidate his power in 1934 violated the Enabling Act. Article 2 of the Act stated that "laws enacted by the government of the Reich may deviate from the constitution as long as they do not affect the institutions of the Reichstag and the Reichsrat. The rights of the President remain unaffected". On 14 February 1934, the "Law on the Abolition of the Reichsrat" eliminated the Reichsrat completely, despite the explicit protection of its existence.[37] When Hindenburg died on 2 August, Hitler appropriated presidential powers for himself in accordance with a law passed the previous day.[38]

Aftermath and legacy

[edit]After the passage of the Enabling Act, the Weimar Constitution was largely forgotten. Hitler nonetheless used it to give his dictatorship the appearance of legality. In the final three Reichstag elections held during his rule (November 1933, March 1936 and April 1938), voters were presented with a single list of Nazis and "guest candidates".[39][40][41] Secret voting technically remained possible, but the Nazis made use of aggressive extra-legal measures at the polling stations to intimidate the electors from attempting to vote in secret. Thousands of Hitler's decrees were based explicitly on the Reichstag Fire Decree, and hence on Article 48.[42]

In Hitler's 1945 political testament (written shortly before his suicide), he appointed Admiral Karl Dönitz to succeed him. He named Dönitz president, not Führer, thereby re-establishing a constitutional office which had lain dormant since Hindenburg's death ten years earlier. Despite the appearance of legality, Hitler failed to transfer power to Dönitz in a fully legal manner, since under the Weimar Constitution, the office of President of the Reich required confirmation of such a nomination in a general election.[43] On 30 April 1945, Dönitz formed what became known as the Flensburg government, which controlled only a tiny area of Germany near the Danish border, including the town of Flensburg. It was dissolved by the Allies on 23 May. On 5 June, the Allied Berlin Declaration proclaimed the assumption of supreme authority by the four victorious powers acting as occupying forces in their respective zones and jointly in the Allied Control Council for Germany as a whole.[44]

The Enabling Act was formally repealed by Article 1a of the Allied Control Council in Control Council Law No. 1 on 20 September 1945,[45] which at least theoretically reestablished the Weimar Constitution. Its legal validity during the Allied occupation of Germany from 1945 to 1949 was, however, overridden by the Allies' power over Germany.

The 1949 Constitution of the German Democratic Republic (East Germany) contained many passages that were directly copied from the 1919 constitution.[46] It was intended to be the constitution of a united Germany and was therefore a compromise between liberal-democratic and Marxist–Leninist ideologies. It was replaced by a new, explicitly Communist constitution in 1968, which remained in force until the reunification of Germany in 1990.

The Basic Law for the Federal Republic of Germany, enacted in 1949, said "provisions of Articles 136, 137, 138, 139 and 141 of the German Constitution of 11 August 1919 shall be an integral part of this Basic Law". These articles of the Weimar Constitution (which dealt with the state's relationship to the different Christian denominations) remain part of the German Basic Law.[21]

Under the judicial system based on the Basic Law, the Weimar Constitution initially retained the force of law (with the exception of the church articles on a non-constitutional level) where the Basic Law contained nothing to the contrary. The norms were, however, largely redundant or dealing with matters reserved to the states and as such officially set out of force within two decades. Aside from the church articles, the rule that titles of nobility were to be considered part of the name and must no longer be bestowed (Art. 109 III) is the only one left in force.[47]

The first official constitution of the Republic of Korea (commonly referred to as South Korea) was based on the Weimar Constitution.[48] It also provided much of the wording for the Constitution of Latvia, which is seen as a synthesis between the Weimar Constitution and Westminster system used in the United Kingdom.[49][50] The Constitution of India drew its language on the suspension of fundamental rights during an emergency from the Weimar Constitution.[51]

Notes

[edit]† Protections provided by Articles 114, 115, 117, 118, 123, 124, and 153 could be suspended or restricted by the president, with the concurrence of the chancellor, through invocation of the authority granted under Article 48 of the Weimar Constitution.

References

[edit]- ^ Blume, Dorlis; Wichmann, Manfred (31 August 2014). "Chronik 1919" [Historical Chronicle 1919]. Deutsches Historisches Museum (in German). Retrieved 16 October 2024.

- ^ Nohlen, Dieter; Stöver, Philip (2010). Elections in Europe: A data handbook. Baden-Baden: Nomos. p. 762. ISBN 978-3-832-95609-7.

- ^ Holste, Heiko (January 2009). "Die Nationalversammlung gehört hierher!" [The National Assembly belongs here!]. Frankfurther Allgemeine Zeitung, Bilder und Zeiten Nr. 8, 10 (in German).

- ^ Michaelis, Andreas (14 September 2014). "Hugo Preuß". Deutsches Historisches Museum (in German). Retrieved 16 October 2024.

- ^ Mommsen, Wolfgang J. (1974). Max Weber und die deutsche Politik 1890–1920 [Max Weber and German Politics 1890–1920] (in German) (2nd ed.). Tübingen: Mohr. pp. 372–375. ISBN 9783165358612.

- ^ Wehler, Hans-Ulrich (2003). Deutsche Gesellschaftsgeschichte [German Social History] (in German). Vol. 4. Munich: C. H. Beck. p. 350. ISBN 978-3-406-32264-8.

- ^ "Vor 100 Jahren: Weimarer Reichsverfassung verabschiedet" [100 Years Ago: The Weimar Constitution Adopted]. Deutscher Bundestag (in German). Retrieved 17 October 2024.

- ^ Nohlen, D & Stöver, P (2010) Elections in Europe: A data handbook, p. 762 ISBN 978-3832956097

- ^ O'Neill, Aaron (21 June 2022). "Approximate German territorial losses, and related loss of resources, following the Treaty of Versailles, June 28, 1919". statista. Retrieved 29 October 2024.

- ^ a b "Reichstag Fire Decree". United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Retrieved 18 October 2024.

- ^ "The Federal Republic of Germany". Deutscher Bundestag. Retrieved 22 October 2024.

- ^ Muharremi, Robert (19 May 2020). "Policy Analysis. Vote of no-confidence and the formation of a new government" (PDF). Friedrich Ebert Stiftung. p. 11. Retrieved 22 October 2024.

- ^ Holborn, Hajo (Autumn 1956). "Prussia and the Weimar Republic". The Johns Hopkins University Press. 23 (3): 335. JSTOR 40969541 – via JSTOR.

- ^ Neugebauer, Wolfgang, ed. (2000). Handbuch der preussischen Geschichte. Band 3: Vom Kaiserreich zum 20. Jahrhundert und grosse Themen der Geschichte Preussens [Handbook of Prussian History. Vol. 3: From the Empire to the 20th Century and Major Themes of Prussian History] (in German). Berlin: De Gruyter. p. 242. ISBN 3-11-014092-6.

- ^ "Das Deutsche Reich. Überblick / Verwaltung" [The German Reich. Overview / Administration]. gonschior.de (in German). Retrieved 20 October 2024.

- ^ Schröder, Valentin (25 July 2014). "Reichsrat. Aufgaben und Zusammensetzung" [Reichsrat: Duties and Composition]. Wahlen in Deutschland (in German). Retrieved 21 October 2024.

- ^ "Preuss Denounces Demand of Allies". The New York Times. 14 September 1919. Retrieved 17 October 2024.

- ^ Grothe, Ewald (8 July 2021). "Ein "Hüter der Verfassung"? Vor 100 Jahren wurde der Staatsgerichtshof in Leipzig errichtet" [A "Guardian of the Constitution"? 100 Years Ago the State Court Was Established in Leipzig.]. Friedrich Naumann Stiftung (in German). Retrieved 21 October 2024.

- ^ "German Civil Code". Encyclopedia Britannica. 28 July 2015. Retrieved 21 October 2015.

- ^ Poll, Robert (May 2020). "The Weimar Constitution". Konrad Adenauer Stiftung. p. 4. Retrieved 21 October 2024.

- ^ a b "Basic Law for the Federal Republic of Germany". Gesetze im Internet. Articles 136, 140. Retrieved 28 October 2024.

- ^ Shirer, William L. (1990). The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich. New York: Simon & Schuster. p. 56. ISBN 978-0-671-72868-7.

- ^ Wehler 2003, p. 348, 350.

- ^ Wehler 2003, p. 350–351.

- ^ Stolleis, Michael (2004). Dunlap, Thomas (ed.). A History of Public Law in Germany 1914–1945. Translated by Dunlap, Thomas. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. p. 58. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199269365.001.0001. ISBN 0-19-926936-X.

- ^ Stolleis 2004, p. 99.

- ^ Wallner, Florian (2023). Der Artikel 48 der Weimarer Reichsverfassung und seine Anwendung unter der Reichspräsidentschaft Friedrich Eberts im Vergleich zur Reichspräsidentschaft Paul von Hindenburgs [Article 48 of the Weimar Constitution and its application under the presidency of Friedrich Ebert in comparison to the presidency of Paul von Hindenburg] (in German). Norderstedt, Germany: Books on Demand. pp. 60–61. ISBN 978-3-757-84964-1.

- ^ Elgie, R.; Moestrup, Sophia; Wu, Y., eds. (2011). Semi-Presidentialism and Democracy. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK. p. 233. ISBN 9780230306424.

- ^ "The Weimar Republic". Holocaust Encyclopedia. Retrieved 24 October 2024.

- ^ "Reichstagswahl Juli 1932" [Reichstag Election July 1932]. gonschior.de (in German). Retrieved 24 October 2024.

- ^ "Gesetz über die Wahl des Reichspräsidenten. Vom 4. Mai 1920" [Law on the Election of the Reich President of 4 May 1920]. documentArchiv.de (in German). Retrieved 25 October 2024.

- ^ "Die Reichspräsidenten 1919–1934" [The Reich Presidents 1919–1934]. gonschior.de (in German). Retrieved 25 October 2024.

- ^ Wehler 2003, pp. 361–364.

- ^ Evans, Richard J (2004): The Coming of the Third Reich; New York, The Penguin Press, p. 88.

- ^ "The Enabling Act". Holocaust Encyclopedia. Retrieved 26 October 2024.

- ^ "Enabling Act". Encyclopedia Britannica. 26 April 2024. Retrieved 26 October 2024.

- ^ Wells, Roger H. (April 1936). "The Liquidation of the German Länder". American Political Science Review. 30 (2): 355. doi:10.2307/1947263. JSTOR 1947263 – via Cambridge University Press.

- ^ "Gesetz über das Staatsoberhaupt des Deutschen Reichs und Erlass des Reichskanzlers zu dessen Vollzug" [Law on the Head of State of the German Reich and the Decree of the Chancellor for its Execution]. 100[0] Schlüsseldokumente zur deutschen Geschichte im 20. Jahrhundert (in German). Retrieved 26 October 2024.

- ^ "National Socialism (1933–1945)". Deutscher Bundestag. Retrieved 27 October 2024.

- ^ Richard J. Evans (26 July 2012). The Third Reich in Power, 1933 - 1939: How the Nazis Won Over the Hearts and Minds of a Nation. Penguin Books Limited. p. 637. ISBN 978-0-7181-9681-3.

- ^ Nohlen, Dieter; Stöver, Philip (2010). Elections in Europe: A data handbook. Baden-Baden: Nomos. p. 762. ISBN 978-3-8329-5609-7.

- ^ "A State of Emergency". The Second World War. Retrieved 27 October 2024.

- ^ Bamford, Tyler (11 June 2020). "Nazi Germany's Last Leader: Admiral Karl Dönitz". The National WWII Museum. Retrieved 27 October 2024.

- ^ Selby, Scott Andrew (2021). The Axmann Conspiracy. Scott Andrew Selby. pp. 57–58.

- ^ – via Wikisource.

- ^ Markovits, Inga. "Constitution Making After National Catastrophes: Germany in 1949 and 1990", William & Mary Law Review. Volume 49. Issue 4. Article 9 (2008). pp. 1307–1346.

- ^ "Die Verfassung des Deutschen Reichs Art 109". Gesetze im Internet. Retrieved 28 October 2024.

- ^ Kwantes, Johan (2009). "The Idea Behind the Constitution: an interview with Chaihark Hahm" (PDF). NIAS. p. 13. Retrieved 3 February 2023.

- ^ Potjomkina, Diāna; Sprūds, Andris; Ščerbinskis, Valters (2016). The centenary of Latvias's foreign affairs: Ideas and personalities. ISBN 978-9984-583-99-0. OCLC 1012747806.

- ^ Apsītis, Romāns; Pleps, Janis (2012). "About The Constitution of the Republic of Latvia: History and Modern Days" (PDF). The Constitution of the Republic of Latvia. Latvijas Vēstnesis. ISBN 978-9984-840-20-8.

- ^ "Constitution Day: Borrowed features in the Indian Constitution from other countries". India Today. Archived from the original on 7 March 2021. Retrieved 12 July 2021.

External links

[edit]- – via Wikisource. Full text of the constitution in English translation