Klezmer

| Klezmer | |

|---|---|

| |

| Native name | קלעזמער |

| Other names | Jewish instrumental folk music, Freylekh music |

| Stylistic origins | |

| Cultural origins | Ashkenazic Jewish ceremonies, especially weddings, in Eastern Europe |

| Typical instruments | Standard orchestra instruments, accordion, cimbalom |

Israeli music |

|---|

| Religious |

| Secular |

| Israel |

| Dance |

| Music for holidays |

Klezmer (Yiddish: קלעזמער or כּלי־זמר) is an instrumental musical tradition of the Ashkenazi Jews of Central and Eastern Europe.[1] The essential elements of the tradition include dance tunes, ritual melodies, and virtuosic improvisations played for listening; these would have been played at weddings and other social functions.[2][3] The musical genre incorporated elements of many other musical genres including Ottoman (especially Greek and Romanian) music, Baroque music, German and Slavic folk dances, and religious Jewish music.[4][5] As the music arrived in the United States, it lost some of its traditional ritual elements and adopted elements of American big band and popular music.[6][7] Among the European-born klezmers who popularized the genre in the United States in the 1910s and 1920s were Dave Tarras and Naftule Brandwein; they were followed by American-born musicians such as Max Epstein, Sid Beckerman and Ray Musiker.[8]

After the destruction of Jewish life in Eastern Europe during the Holocaust, and a general fall in the popularity of klezmer music in the United States, the music began to be popularized again in the late 1970s in the so-called Klezmer Revival.[1] During the 1980s and onwards, musicians experimented with traditional and experimental forms of the genre, releasing fusion albums combining the genre with jazz, punk, and other styles.[9]

Etymology

[edit]The term klezmer, as used in the Yiddish language, has a Hebrew etymology: klei, meaning "tools, utensils or instruments of" and zemer, "melody"; leading to k'lei zemer כְּלֵי זֶמֶר, meaning "musical instruments".[10][1] This expression would have been familiar to literate Jews across the diaspora, not only Ashkenazi Jews in Eastern Europe.[11] Over time the usage of "klezmer" in a Yiddish context evolved to describe musicians instead of their instruments, first in Bohemia in the second half of the sixteenth century and then in Poland, possibly as a response to the new status of the musicians who were at that time forming professional guilds.[11] Previously the musician may have been referred to as a lets (לץ) or other terms.[12][13] After the term klezmer became the preferred term for these professional musicians in Yiddish-speaking Eastern Europe, other types of musicians were more commonly known as muziker or muzikant.

It was not until the late 20th century that the word "klezmer" became a commonly known English-language term.[14] During that time, through metonymy it came to refer not only to the musician but to the musical genre they played, a meaning which it had not had in Yiddish.[15][16][17] Early 20th century recording industry materials and other writings had referred to it as Hebrew, Jewish, or Yiddish dance music, or sometimes using the Yiddish term Freilech music ("Cheerful music").

Twentieth century Russian scholars sometimes used the term klezmer; Ivan Lipaev did not use it, but Moisei Beregovsky did when publishing in Yiddish or Ukrainian.[11]

The first[citation needed] postwar recordings to use the term "klezmer" to refer to the music were The Klezmorim's East Side Wedding and Streets of Gold in 1977/78, followed by Andy Statman and Zev Feldman's Jewish Klezmer Music in 1979.[citation needed]

Musical elements

[edit]Style

[edit]The traditional style of playing klezmer music, including tone, typical cadences, and ornamentation, sets it apart from other genres.[18] Although klezmer music emerged from a larger Eastern European Jewish musical culture that included Jewish cantorial music, Hasidic Niguns, and later Yiddish theatre music, it also borrowed from the surrounding folk musics of Central and Eastern Europe and from cosmopolitan European musical forms.[4][19] Therefore it evolved into an overall style which has recognizable elements from all of those other genres.

Few klezmer musicians before the late nineteenth century had formal musical training, but they inherited a rich tradition with its own advanced musical techniques. Each musician had their understanding of how the style should be "correctly" performed.[20][18] The usage of these ornaments was not random; the matters of "taste", self-expression, variation and restraint were and remain important elements of how to interpret the music.[18]

Klezmer musicians apply the overall style to available specific techniques on each melodic instrument. They incorporate and elaborate the vocal melodies of Jewish religious practice, including khazones, davenen, and paraliturgical song, extending the range of human voice into the musical expression possible on instruments.[21] Among those stylistic elements that are considered typically "Jewish" in klezmer music are those which are shared with cantorial or Hasidic vocal ornaments, including imitations of sighing or laughing.[22] Various Yiddish terms were used for these vocal-like ornaments such as קרעכץ (Krekhts, "groan" or "moan"), קנײטש (kneytsh, "wrinkle" or "fold"), and קװעטש (kvetsh, "pressure" or "stress").[10] Other ornaments such as trills, grace notes, appoggiaturas, glitshn (glissandos), tshoks (a kind of bent notes of cackle-like sound), flageolets (string harmonics),[23][24] pedal notes, mordents, slides and typical klezmer cadences are also important to the style.[18] In particular, the cadences which draw on religious Jewish music identify a piece more strongly as a klezmer tune, even if its broader structure was borrowed from a non-Jewish source.[25][19] Sometimes the term dreydlekh is used only for trills, while other use it for all klezmer ornaments.[26] Unlike in Classical music, vibrato is used sparingly, and is treated as another type of ornament.[22][18]

In an article about Jewish music in Romania, Bob Cohen of Di Naye Kapelye describes krekhts as "a sort of weeping or hiccoughing combination of backwards slide and flick of the little finger high above the base note, while the bow does, well, something – which aptly imitates Jewish liturgical singing style." He also noted that the only other place he has heard this particular ornamentation is in Turkish music on the violin.[27] Yale Strom wrote that the use of dreydlekh by American violinists gradually diminished since the 1940s, but with the klezmer revival in 1970, dreydlekh had become prominent again.[28]

The accompaniment style of the accompanist or orchestra could be fairly impromptu, called צוהאַלטן (tsuhaltn, holding onto).[29]

Historical repertoire

[edit]The repertoire of klezmer musicians was very diverse and tied to specific social functions and dances, especially of the traditional wedding.[2][19] These melodies might have a non-Jewish origin, or have been composed by a klezmer, but only rarely are they attributed to a specific composer.[30] Generally klezmer music can be divided into two broad categories: music for specific dances, and music for listening (at the table, in processions, ceremonial, etc.).[30]

Dances

[edit]- Freylekhs. The simplest and most widespread type of klezmer dance tunes are those played in 2

4 and intended for group circle dances. Depending on the location this basic dance may also have been called a Redl (circle), Hopke, Karahod (round dance, literally the Belarusian translation of the Russian khorovod), Dreydl, Rikudl, etc.[2][31][29][10] - Bulgar, or Bolgar, became the most popular klezmer dance form in the United States. Its origin is thought to be in Moldavia and with a deep connection to the Sârbă genre there.[19]

- Sher is a contra dance in 2

4. Beregovsky, writing in the 1930s, noted that despite the dance being very commonly played across a wide area, he suspected that it had its roots in an older German dance.[2] This dance continued to be known in the United States even after other complex European klezmer dances had been forgotten.[32] In some regions the music of a Sher could be interchangeable with a Freylekhs.[19] - Khosidl, or Khosid, named after Hasidic Jews, is a more dignified embellished dance in 2

4 or 4

4. The dance steps can be performed in a circle or in a line. - Hora or Zhok (from the Romanian Joc) is a circle dance in 3

8. In the United States, it came to be one of the main dance types after the Bulgar.[19] - Broygez-tants[30]

- Kolomeike is a fast and catchy dance in 2

4 time, which originated in Ukraine, and is prominent in the folk music of that country. - Skotshne is generally thought to be a more elaborate Freylekhs which could be played either for dancing or listening.[2]

- Nigun, a very broad term which can refer to melodies for listening, singing or dancing.[10] Usually a mid-paced song in 2

4. - Waltzes were very popular, whether classical, Russian, or Polish. A padespan was a sort of Russian/Spanish waltz known to klezmers.

- Mazurka and polka, Polish and Czech dances, respectively, were often played for both Jews and Gentiles.

- Sirba – a Romanian dance in 2

2 or 2

4 (Romanian sârbă). It features hopping steps and short bursts of running, accompanied by triplets in the melody.

Non-dance repertoire

[edit]- The Doyne is a freeform instrumental form borrowed from the Romanian shepherd's doina. Although there are many regional types of doina in Romania and Moldova, the Jewish form is typically simpler, with a minor key theme which is then repeated in a major key, followed by a Freylekhs.[30] A Volekhl is a related genre.[10]

- Tish-nign (table tune)[10]

- Moralish, a type of Nigun, called Devekut in Hebrew, which inspires spiritual arousal or a pious mood.[10][29]

- A Vals (Waltz), pieces in 3

4 especially in the Hasidic context, may be slower than non-Jewish waltzes and intended for listening while the wedding parties are seated at their tables.[10] - Forms centering on bridal rituals, including Kale-bazetsn (seating of the bride)

- A Marsh (March) can be non-Jewish march melodies adapted into joyful singing or playing contexts.[10]

- Processional melodies, including Gas-nigunim (street tunes), Tsum tish (to the table). According to Beregovski the Gas-nign was always in 3

4 time.[30] - The Taksim, whose name is borrowed from the Ottoman/Arab Taqsim is a freeform fantasy on a particular motif, ornamented with trills, roulades and so on; it usually ends with a Freylekhs.[30] By the twentieth century it had mostly become obsolete and was replaced by the doina.[33]

- Fantazi or fantasy is a freeform song, traditionally played at Jewish weddings to the guests as they dined. It resembles the fantasia of "light" classical music.

- A Terkisher is a type of virtuosic solo piece in 4

4 performed by leading klezmorim such as Dave Tarras and Naftule Brandwein. There is no dance for this type of melody, rather it references an Ottoman or "oriental" style, and melodies may incorporate references to Greek Hasapiko into an Ashkenazic musical aesthetic. - Parting melodies played at the beginning or end of a wedding day, such as the Zay gezunt (be healthy), Gas-nign, Dobriden (good day), Dobranotsh or A gute nakht (good night) etc.[30][34] These types of pieces were sometimes in 3

4 which may have given an air of dignity and seriousness.[35]

Orchestration

[edit]Klezmer music is an instrumental tradition, without much of a history of songs or singing. In Eastern Europe, Klezmers did traditionally accompany the vocal stylings of the Badchen (wedding entertainer), although their performances were typically improvised couplets and the calling of ceremonies rather than songs.[36][37] (The importance of the Badchen gradually decreased by the twentieth century, although they still continued in some traditions.[38])

As for the klezmer orchestra, its size and composition varied by time and place. The klezmer bands of the eighteenth and early nineteenth century were small, with roughly three to five musicians playing woodwind or string instruments.[20] Another common configuration in that era was similar to Hungarian bands today, typically a lead violinist, second violin, cello, and cimbalom.[39][40] In the mid-nineteenth century, the Clarinet started to appear in those small Klezmer ensembles as well.[41] By the last decades of the century, in Ukraine, the orchestras had grown larger, averaging seven to twelve members, and incorporating brass instruments and up to twenty for a prestigious occasion.[42][43] (However, for poor weddings a large klezmer ensemble might only send three or four of its junior members.[42]) In these larger orchestras, on top of the core instrumentation of strings and woodwinds, cornets, C clarinets, trombones, a contrabass, a large Turkish drum, and several extra violins.[30] The inclusion of Jews in tsarist army bands during the 19th century may also have led to the introduction of typical military band instruments into klezmer. With such large orchestras, the music was arranged so that the bandleader soloist could still be heard at key moments.[44] In Galicia, and Belarus, the smaller string ensemble with cimbalom remained the norm into the twentieth century.[45][30] American klezmer as it developed in dancehalls and wedding banquets of the early twentieth century had a more complete orchestration not unlike those used in popular orchestras of the time. They use a clarinet, saxophone, or trumpet for the melody, and make great use of the trombone for slides and other flourishes.

The melody in klezmer music is generally assigned to the lead violin, although occasionally the flute and eventually clarinet.[30] The other instrumentalists provide harmony, rhythm, and some counterpoint (the latter usually coming from the second violin or viola). The clarinet now often plays the melody. Brass instruments—such as the French valved cornet and keyed German trumpet—eventually inherited a counter-voice role.[46] Modern klezmer instrumentation is more commonly influenced by the instruments of the 19th-century military bands than the earlier orchestras.

Percussion in early 20th-century klezmer recordings was generally minimal—no more than a wood block or snare drum. In Eastern Europe, percussion was often provided by a drummer who played a frame drum, or poyk, sometimes called baraban. A poyk is similar to a bass drum and often has a cymbal or piece of metal mounted on top, which is struck by a beater or a small cymbal strapped to the hand.

Melodic modes

[edit]Western, Cantorial, and Ottoman music terminology

[edit]Klezmer music is a genre that developed partly in the Western musical tradition but also in the Ottoman Empire, and is primarily an oral tradition which does not have a well-established literature to explain its modes and modal progression.[47][48] But, as with other types of Ashkenazic Jewish music, it has a complex system of modes which were used in its compositions.[10][49] Many of its melodies do not fit well in the major and minor terminology used in Western music, nor is the music systematically microtonal in the way that Middle Eastern music is.[47] Nusach terminology, as developed for Cantorial music in the nineteenth century, is often used instead, and indeed many klezmer compositions draw heavily on religious music.[34] But it also incorporates elements of Baroque and Eastern European folk musics, making description based only on religious terminology incomplete.[25][29][50] Still, since the Klezmer revival of the 1970s, the terms for Jewish prayer modes are the most common to describe those used in klezmer.[51] The terms used in Yiddish for these modes include nusach (נוסח); shteyger (שטײגער), "manner, mode of life", which describes the typical melodic character, important notes and scale; and gust (גוסט), a word meaning "taste" which was commonly used by Moisei Beregovsky.[29][30][48]

Beregovsky, who was writing in the Stalinist era and was constrained by having to downplay klezmer's religious aspects, did not use the terminology of synagogue modes, except in some early work in 1929. Instead, he relied on German-inspired musical terminology of major, minor, and "other" modes, which he described in technical terms.[30][52] In his 1940s works he noted that the majority of the klezmer repertoire seemed to be in a minor key, whether natural minor or others, that around a quarter of the material was in Freygish, and that around a fifth of the repertoire was in a major key.[30]

Another set of terminology sometimes used to describe klezmer music is that of the Makams used in Ottoman and other Middle Eastern music.[51][53] This approach dates back to Idelsohn in the early twentieth century, who was very familiar with Middle Eastern music, and has been developed in the past decade by Joshua Horowitz.[54][50][51][47]

Finally, some Klezmer music, and especially that composed in the United States from the mid-twentieth century onwards, may not be composed with these traditional modes, but rather built around chords.[25]

Description

[edit]Because there is no agreed-upon, complete system for describing modes in Klezmer music, this list is imperfect and may conflate concepts which some scholars view as separate.[49][54] Another problem in listing these terms as simple eight-note (octatonic) scales is that it makes it harder to see how Klezmer melodic structures can work as five-note pentachords, how parts of different modes typically interact, and what the cultural significance of a given mode might be in a traditional Klezmer context.[47][48]

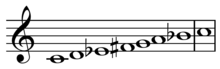

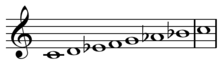

- Freygish, Ahavo Rabboh, or Phrygian dominant scale resembles the Phrygian mode, having a flat second but also a permanent raised third.[55] It is among the most common modes in Klezmer and is closely identified with Jewish identity; Beregovsky estimated that roughly a quarter of the Klezmer music he had collected was in Freygish.[30][47] Among the most well-known pieces composed in this mode are "Hava Nagila" and "Ma yofus". It is comparable to the Maqam Hijaz found in Arabic music.[47]

- Mi Sheberakh, Av HaRachamim, "altered Dorian" or Ukrainian Dorian scale is a minor mode which has a raised fourth.[55] It is sometimes compared to Nikriz Makamı. It is closely related to Freygish since they share the same pitch intervals.[47] This mode is often encountered in Doynes and other Klezmer forms with connections to Romanian or Ukrainian music.

- Adonoy Molokh or Adoyshem Molokh a synagogue mode with a flatted seventh.[29] It is sometimes called the "Jewish major".[54] It has some similarities to the Mixolydian mode.[55]

- Mogen Ovos is a synagogue mode which resembles the Western natural minor.[29] In klezmer music, it is often found in greeting and parting pieces, as well as dance tunes.[47] It has some similarities to the Bayati maqam used in Arabic and Turkish music.

- Yishtabakh resembles Mogen Ovos and Freygish. It is a variant of the Mogen Ovos scale that frequently flattens the second and fifth degrees.[56]

History

[edit]Europe

[edit]Development of the genre

[edit]The Bible has several descriptions of orchestras and Levites making music, but after the destruction of the Second Temple in 70 CE, many rabbis discouraged musical instruments.[57] Therefore, while there may have been Jewish musicians in different times and places since then, the "Klezmer" arose much more recently.[58] The earliest written record of the use of the word was identified by Isaac Rivkind as being in a Jewish council meeting from Kraków in 1595.[59][60] They may have existed even earlier in Prague, as references to them have been found as early as 1511 and 1533.[61] It was in the 1600s that the situation of Jewish musicians in Poland improved, as they gained the right to form Guilds (Khevre), and therefore to set their own fees, hire Christians, and so on.[62] Therefore over time this new form of professional musician developed new forms of music and elaborated this tradition across a wide area of Eastern European Jewish life. The rise of Hasidic Judaism in the late eighteenth century and onwards also contributed to the development of klezmer, due to their emphasis on dancing and wordless melodies as a component of Jewish practice.[17]

The Eastern European klezmer profession (1700–1930s)

[edit]

The nineteenth century also saw the rise of a number of klezmer violin virtuosos who combined the techniques of classical violinists such as Ivan Khandoshkin and of Bessarabian folk violinists, and who composed dance and display pieces that became widespread even after the composers were gone.[63] Among these figures were Aron-Moyshe Kholodenko "Pedotser", Yosef Drucker "Stempenyu", Alter Goyzman "Alter Chudnover" and Josef Gusikov.[64][65][66][67]

Unlike in the United States, where there was a robust Klezmer recording industry, there was relatively less recorded in Europe in the early twentieth century. The majority of European recordings of Jewish music consisted of Cantorial and Yiddish Theatre music, with only a few dozen known to exist of Klezmer music.[68] These include violin pieces by artists such as Oscar Zehngut, Jacob Gegna, H. Steiner, Leon Ahl, and Josef Solinski; flute pieces by S. Kosch, and ensemble recordings by Belf's Romanian Orchestra, the Russian-Jewish Orchestra, Jewish Wedding Orchestra, and Titunshnayder's Orchestra.[68][69]

Klezmer in the late Russian empire and Soviet era

[edit]The loosening of restrictions on Jews in the Russian Empire, and their newfound access to academic and conservatory training, created a class of scholars who began to reexamine and evaluate klezmer using modern techniques.[30] Abraham Zevi Idelsohn was one such figure, who sought to find an ancient Middle Eastern origin for Jewish music in the diaspora.[70] There was also new interest in collecting and studying Jewish music and folklore, including Yiddish songs, folk tales, and instrumental music. An early expedition was by Joel Engel, who collected folk melodies in his birthplace of Berdyansk in 1900. The first figure to collect large amounts of klezmer music was Susman Kiselgof, who made several expeditions to the Pale of Settlement from 1907 to 1915.[71] He was soon followed by other scholars such as Moisei Beregovsky and Sofia Magid, Soviet scholars of Yiddish and klezmer music.[72][30] Most of the materials collected in those expeditions are now held by the Vernadsky National Library of Ukraine.[73]

Beregovsky, writing in the late 1930s, lamented how little scholars knew about the range of playing technique and social context of Klezmers from past eras, except for the late nineteenth century which could be investigated through elderly musicians who still remembered it.[2]

Jewish music in the Soviet Union, and the continued use of klezmer music, went through several phases of official support or censorship. The officially supported Soviet Jewish musical culture of 1920s involved works based on or satirizing traditional melodies and themes, whereas those of the 1930s were often "Russian" cultural works translated into a Yiddish context.[74] After 1948, Soviet Jewish culture entered a phase of repression, meaning that Jewish music concerts, whether tied to Hebrew, Yiddish, or instrumental klezmer, were no longer allowed to be performed.[75] Moisei Beregovsky's academic work was shut down in 1949 and he was arrested and deported to Siberia in 1951.[76][77] The repression was eased in the mid-1950s as some Jewish and Yiddish performances were allowed to return to the stage once again.[78] However, the main venue for klezmer has always been traditional community events and weddings, not the concert stage or academic institute; those traditional venues were repressed along with Jewish culture in general, according to anti-religious Soviet policy.[79]

United States

[edit]Early American klezmer (1880s–1910s)

[edit]The first klezmers to arrive in the United States followed the first large waves of Eastern European Jewish immigration which began after 1880, establishing themselves mainly in large cities like New York, Philadelphia and Boston.[17] Klezmers—often younger members of klezmer families, or less established musicians—started to arrive from the Russian Empire, the Kingdom of Romania and Austria-Hungary.[80] Some of them found work in restaurants, dance halls, union rallies, wine cellars, and other modern venues in places like New York's Lower East Side.[81][82] But the major source of income for klezmer musicians seems to have remained weddings and Simchas, as in Europe.[83] Those early generations of klezmers are much more poorly documented than those working in the 1910s and 1920s; many never recorded or published music, although some are remembered through family or community history, such as the Lemish klezmer family of Iași, Romania, who arrived in Philadelphia in the 1880s and established a klezmer dynasty there.[84][83]

Big band klezmer orchestras (1910s–1920s)

[edit]

The vitality of the Jewish music industry in major American cities attracted ever more klezmers from Europe in the 1910s. This coincided with the development of the recording industry, which recorded a number of these klezmer orchestras. By the time of the First World War, the industry turned its attention to ethnic dance music and a number of bandleaders were hired by record companies such as Edison Records, Emerson Records, Okeh Records, and the Victor Recording Company to record 78 rpm discs.[85] The first of these was Abe Elenkrig, a barber and cornet player from a klezmer family in Ukraine whose 1913 recording Fon der Choope (From the Wedding) has been recognized by the Library of Congress.[86][87][88]

Among the European-born klezmers recording during that decade were some from the Ukrainian territory of the Russian Empire (Abe Elenkrig, Dave Tarras, Shloimke Beckerman, Joseph Frankel, and Israel J. Hochman), some from Austro-Hungarian Galicia (Naftule Brandwein, Harry Kandel and Berish Katz), and some from Romania (Abe Schwartz, Max Leibowitz, Max Yankowitz, Joseph Moskowitz).[89][90][91][92]

The mid-1920s also saw a number of popular novelty "Klezmer" groups which performed on the radio or vaudeville stages. These included Joseph Cherniavsky's Yiddish-American Jazz Band, whose members would dress as parodies of Cossacks or Hasidim.[93] Another such group was the Boibriker Kapelle, which performed on the radio and in concerts trying to recreate a nostalgic, old-fashioned Galician Klezmer sound.[94] With the passing of the Immigration Act of 1924, which greatly restricted Jewish immigration from Europe, and then the onset of the Great Depression by 1930, the market for Yiddish and klezmer recordings in the United States saw a steep decline, which essentially ended the recording career of many of the popular bandleaders of the 1910s and 1920s, and made the large klezmer orchestra less viable.[95]

Celebrity clarinetists

[edit]Along with the rise of klezmer "big bands" in the 1910s and 1920s, a handful of Jewish clarinet players who had led those bands became celebrities in their own right, with a legacy that lasted into subsequent decades. The most popular among these were Naftule Brandwein, Dave Tarras, and Shloimke Beckerman.[96][97][98]

Klezmer revival

[edit]In the mid-to-late 1970s there was a klezmer revival in the United States and Europe, led by Giora Feidman, The Klezmorim, Zev Feldman, Andy Statman, and the Klezmer Conservatory Band. They drew their repertoire from recordings and surviving musicians of U.S. klezmer.[99] In particular, clarinetists such as Dave Tarras and Max Epstein became mentors to this new generation of klezmer musicians.[100] In 1985, Henry Sapoznik and Adrienne Cooper founded KlezKamp to teach klezmer and other Yiddish music.[101]

The 1980s saw a second wave of revival, as interest grew in more traditionally inspired performances with string instruments, largely with non-Jews of the United States and Germany. Musicians began to track down older European klezmer, by listening to recordings, finding transcriptions, and making field recordings of the few klezmorim left in Eastern Europe. Key performers in this style are Joel Rubin, Budowitz, Khevrisa, Di Naye Kapelye, Yale Strom, The Chicago Klezmer Ensemble, The Maxwell Street Klezmer Band, the violinists Alicia Svigals, Steven Greenman,[102] Cookie Segelstein and Elie Rosenblatt, flutist Adrianne Greenbaum, and tsimbl player Pete Rushefsky. Bands like Brave Old World, Hot Pstromi and The Klezmatics also emerged during this period.

In the 1990s, musicians from the San Francisco Bay Area helped further interest in klezmer music by taking it into new territory. Groups such as the New Klezmer Trio inspired a new wave of bands merging klezmer with other forms of music, such as John Zorn's Masada and Bar Kokhba, Naftule's Dream, Don Byron's Mickey Katz project and violinist Daniel Hoffman's klezmer/jazz/Middle-Eastern fusion band Davka.[99] The New Orleans Klezmer All-Stars[103] also formed in 1991 with a mixture of New Orleans funk, jazz, and klezmer styles.

Starting in 2008, "The Other Europeans" project, funded by several EU cultural institutions,[104] spent a year doing intensive field research in the region of Moldavia under the leadership of Alan Bern and scholar Zev Feldman. They wanted to explore klezmer and lăutari roots, and fuse the music of the two "other European" groups. The resulting band now performs internationally.

A separate klezmer tradition had developed in Israel in the 20th century. Clarinetists Moshe Berlin and Avrum Leib Burstein are known exponents of the klezmer style in Israel. To preserve and promote klezmer music in Israel, Burstein founded the Jerusalem Klezmer Association, which has become a center for learning and performance of klezmer music in the country.[105]

Since the late 1980s, an annual klezmer festival is held every summer in Safed, in the north of Israel.[106][107]

Popular culture

[edit]In music

[edit]While traditional performances may have been on the decline, many Jewish composers who had mainstream success, such as Leonard Bernstein and Aaron Copland, continued to be influenced by the klezmeric idioms heard during their youth (as Gustav Mahler had been). George Gershwin was familiar with klezmer music, and the opening clarinet glissando of "Rhapsody in Blue" suggests this influence, although the composer did not compose klezmer directly.[108] Some clarinet stylings of swing jazz bandleaders Benny Goodman and Artie Shaw can be interpreted as having been derived from klezmer, as can the "freilach swing" playing of other Jewish artists of the period such as trumpeter Ziggy Elman.

At the same time, non-Jewish composers were also turning to klezmer for a prolific source of fascinating thematic material. Dmitri Shostakovich in particular admired klezmer music for embracing both the ecstasy and the despair of human life, and quoted several melodies in his chamber masterpieces, the Piano Quintet in G minor, op. 57 (1940), the Piano Trio No. 2 in E minor, op. 67 (1944), and the String Quartet No. 8 in C minor, op. 110 (1960).

The compositions of Israeli-born composer Ofer Ben-Amots incorporate aspects of klezmer music, most notably his 2006 composition Klezmer Concerto. The piece is for klezmer clarinet (written for Jewish clarinetist David Krakauer),[109] string orchestra, harp and percussion.[110]

In visual art

[edit]

The figure of the klezmer, as a romantic symbol of nineteenth century Jewish life, appeared in the art of a number of twentieth century Jewish artists such as Anatoli Lvovich Kaplan, Issachar Ber Ryback, Marc Chagall, and Chaim Goldberg. Kaplan, making his art in the Soviet Union, was quite taken by the romantic images of the Klezmer in literature, and in particular in Sholem Aleichem's Stempenyu, and depicted them in rich detail.[111]

In film

[edit]- Yidl Mitn Fidl (1936), directed by Joseph Green

- Fiddler on the Roof (1971), directed by Norman Jewison

- Les Aventures de Rabbi Jacob (1973), directed by Gérard Oury

- Jewish Soul Music: The Art of Giora Feidman (1980), directed by Uri Barbash

- A Jumpin' Night in the Garden of Eden (1988), directed by Michal Goldman

- Fiddlers on the Hoof (1989), directed by Simon Broughton

- The Last Klezmer: Leopold Kozlowski: His Life and Music (1994), directed by Yale Strom

- Beyond Silence (1996), about a klezmer-playing clarinetist, directed by Charlotte Link

- A Tickle in the Heart (1996), directed by Stefan Schwietert[112]

- Itzhak Perlman: In the Fiddler's House (1996), aired 29 June 1996 on Great Performances (PBS/WNET television series)

- L'homme est une femme comme les autres (1998, directed by Jean-Jacques Zilbermann with soundtrack by Giora Feidman)

- Dummy (2002), directed by Greg Pritikin

- Klezmer on Fish Street (2003), directed by Yale Strom

- Le Tango des Rashevski (2003) directed by Sam Garbarski

- Klezmer in Germany (2007), directed by Kryzstof Zanussi and C. Goldie

- A Great Day on Eldridge Street (2008), directed by Yale Strom

- The "Socalled" Movie (2010), directed by Garry Beitel

In literature

[edit]In Jewish literature, the klezmer was often represented as a romantic and somewhat unsavory figure.[113] However, in nineteenth century works by writers such as Mendele Mocher Sforim and Sholem Aleichem they were also portrayed as great artists and virtuosos who delighted the masses.[30] Klezmers also appeared in non-Jewish Eastern European literature, such as in the epic poem Pan Tadeusz, which depicted a character named Jankiel Cymbalist, or in the short stories of Leopold von Sacher-Masoch.[12] In George Eliot's Daniel Deronda (1876), the German Jewish music teacher is named Herr Julius Klesmer.[114] The novel was later adapted into a Yiddish musical by Avram Goldfaden titled Ben Ami (1908).[115]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c Strom, Yale (Winter 2024). "The Mesmerizing Sounds of Klezmer". Humanities: The Magazine of the National Endowment for the Humanities. Retrieved 27 December 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f Beregovsky, Moishe (1982). "4. Jewish Instrumental Folk Music (1937)". In Slobin, Mark (ed.). Old Jewish folk music : the collections and writings of Moshe Beregovski. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. pp. 530–548. ISBN 081227833X.

- ^ Rubin, Joel E. (2020). New York klezmer in the early twentieth century: the music of Naftule Brandwein and Dave Tarras. Rochester, NY: Boydell & Brewer. p. 29. ISBN 9781580465984.

- ^ a b Slobin, Mark (2000). Fiddler on the move : exploring the klezmer world. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 7. ISBN 9780195161809.

- ^ Feldman, Zev (2016). Klezmer: music, history and memory. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. pp. 208–210. ISBN 9780190244514.

- ^ Rubin, Joel E. (2020). New York klezmer in the early twentieth century: the music of Naftule Brandwein and Dave Tarras. Rochester, NY: Boydell & Brewer. pp. 71–74. ISBN 9781580465984.

- ^ Feldman, Zev (2016). Klezmer: music, history and memory. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. pp. 216–8. ISBN 9780190244514.

- ^ Feldman, Zev. "Music: Traditional and Instrumental Music". YIVO Encyclopedia. YIVO.

- ^ Kirshenblatt-Gimblett, Barbara (1998). "Sounds of Sensibility". Judaism. 47: 49–55.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Mazor, Yaacov; Seroussi, Edwin (1990). "Towards a Hasidic Lexicon of Music". Orbis Musicae. 10: 118–43.

- ^ a b c Feldman, Zev (2016). Klezmer: music, history and memory. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. pp. 61–67. ISBN 9780190244521.

- ^ a b Feldman, Zev. "Music: Traditional and Instrumental Music". YIVO Encyclopedia. YIVO Institute. Retrieved 20 June 2021.

- ^ Liptzin, Solomon (1972). A history of Yiddish literature. Middle Village, N.Y.: Jonathan David. ISBN 0824601246.

- ^ Schultz, Julia (September 2019). "The impact of Yiddish on the English language: An overview of lexical borrowing in the variety of subject areas and spheres of life influenced by Yiddish over time". English Today. 35 (3): 2–7. doi:10.1017/S0266078418000494. S2CID 150270104.

- ^ Alexander, Phil (2021). Sounding Jewish in Berlin: klezmer music and the contemporary city. Oxford New York, [New York]: Oxford University Press. p. 87. ISBN 9780190064433.

- ^ Slobin, Mark (2000). Fiddler on the move: exploring the klezmer world. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 6. ISBN 9780195161809.

- ^ a b c Netsky, Hankus (Winter 1998). "An overview of klezmer music and its development in the U.S.". Judaism. 47 (1): 5–12.

- ^ a b c d e Rubin, Joel E. (2020). New York klezmer in the early twentieth century : the music of Naftule Brandwein and Dave Tarras. Rochester, NY: Boydell & Brewer. p. 176. ISBN 9781580465984.

- ^ a b c d e f Feldman, Zev (2022). "Musical Fusion and Allusion in the Core and the Transitional Klezmer Repertoires". Shofar: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Jewish Studies. 40 (2): 143–166. doi:10.1353/sho.2022.0026. ISSN 1534-5165. S2CID 253206627.

- ^ a b Rubin, Joel (2009). "'Like a String of Pearls': Reflections on the Role of Brass Instrumentalists in Jewish Instrumental Klezmer Music and the Trope of 'Jewish Jazz'". In Weiner, Howard T. (ed.). Early Twentieth-Century Brass Idioms. Lanham, MD: The Scarecrow Press. pp. 77–102. ISBN 978-0810862456.

- ^ Feldman, Zev (2016). Klezmer: music, history and memory. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. p. 39. ISBN 9780190244514.

- ^ a b Slobin, Mark (2000). Fiddler on the move : exploring the klezmer world. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 98–122. ISBN 9780195161809.

- ^ Yale Strom, "The absolutely complete klezmer songbook", 2006, ISBN 0-8074-0947-2, Introduction

- ^ Strom 2012, pp. 101, 102

- ^ a b c Feldman, Zev (2016). Klezmer: music, history and memory. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. pp. 375–385. ISBN 9780190244521.

- ^ Chris Haigh, The Fiddle Handbook, 2009, Example 4.9

- ^ Cohen.

- ^ Yale Strom, Shpil: The Art of Playing Klezmer, 2012, p. 94

- ^ a b c d e f g Avenary, Hanoch (1960). "The Musical Vocabulary of Ashkenazic Hazanim". Studies in Biblical and Jewish Folklore. Bloomington, Indiana: 187–198.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Beregovski, M. (1941). "Yidishe klezmer, zeyer shafn un shteyger". Literarisher Alamanakh "Sovetish" (in Yiddish). 12. Moscow: Melukhe-farlag "Der Emes": 412–450.

- ^ Feldman, Zev (2016). Klezmer: music, history and memory. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. pp. 275–298. ISBN 9780190244514.

- ^ Feldman, Zev (2016). Klezmer: music, history and memory. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. pp. 261–273. ISBN 9780190244514.

- ^ Feldman, Zev (2016). Klezmer: music, history and memory. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. p. 147. ISBN 9780190244521.

- ^ a b Feldman, Zev (2016). Klezmer: music, history and memory. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. pp. 220–227. ISBN 9780190244521.

- ^ Feldman, Zev (2016). Klezmer: music, history and memory. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. pp. 232–233. ISBN 9780190244521.

- ^ Pietruszka, Symcha (1932). Yudishe entsiḳlopedye far Yudishe geshikhṭe, ḳulṭur, religye, filozofye, liṭeraṭur, biografye, bibliografye un andere Yudishe inyonim (in Yiddish). Warsaw: Yehudiyah. pp. 163–166.

- ^ Feldman, Zev (2016). Klezmer: music, history and memory. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. pp. 146–156. ISBN 9780190244514.

- ^ Rubin, Ruth (1973). Voices of a people : the story of Yiddish folksong (2nd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill. p. 251. ISBN 0070541949.

- ^ Feldman, Zev (2016). Klezmer: music, history and memory. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. pp. 100–111. ISBN 9780190244514.

- ^ Gifford, Paul M. (2001). The hammered dulcimer: a history. Lanham, Md.: Scarecrow Press. pp. 106–107. ISBN 9781461672906.

- ^ Feldman, Zev (2016). Klezmer: music, history and memory. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. pp. 111–113. ISBN 9780190244514.

- ^ a b Feldman, Zev (2016). Klezmer: music, history and memory. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. pp. 93–96. ISBN 9780190244521.

- ^ Левик, Сергей Юрьевич (1962). Записки оперного певца (in Russian). Искусство. pp. 18–19.

- ^ Feldman, Zev (2016). Klezmer: music, history and memory. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. p. 115. ISBN 9780190244514.

- ^ Feldman, Zev (2016). Klezmer: music, history and memory. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. pp. 100–116. ISBN 9780190244514.

- ^ "KLEZMER MUSIC". users.ch. Retrieved 19 January 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Horowitz, Joshua. "The Klezmer Ahava Rabboh Shteyger: Mode, Sub-mode, and Modal Progression" (PDF). Budowitz.com. Retrieved 26 June 2021.

- ^ a b c Rubin, Joel E. (2020). New York klezmer in the early twentieth century : the music of Naftule Brandwein and Dave Tarras. Rochester, NY: Boydell & Brewer. pp. 122–74. ISBN 9781580465984.

- ^ a b Tarsi, Boaz. "Full Text: Cross-Repertoire Motifs in Liturgical Music of the Ashkenazi Tradition: An Initial Lay of the Land by Boaz Tarsi". Jewish Music Research Centre. Retrieved 27 June 2021.

- ^ a b Frigyesi, Judit Laki (1982–1983). "Modulation as an Integral Part of the Modal System in Jewish Music". Musica Judaica. 5 (1): 52–71. JSTOR 23687593.

- ^ a b c Rubin, Joel E. (2020). New York klezmer in the early twentieth century : the music of Naftule Brandwein and Dave Tarras. Rochester, NY: Boydell & Brewer. p. 361. ISBN 9781580465984.

- ^ Feldman, Zev (2016). Klezmer: music, history and memory. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. p. 40. ISBN 9780190244521.

- ^ Alford-Fowler, Julia (May 2013). Chasing Yiddishkayt: A concerto in the context of Klezmer music (PDF) (Doctoral thesis). Temple University. Retrieved 16 June 2021.

- ^ a b c Tarsi, Boaz (3 July 2017). "At the Intersection of Music Theory and Ideology: A. Z. Idelsohn and the Ashkenazi Prayer Mode Magen Avot". Journal of Musicological Research. 36 (3): 208–233. doi:10.1080/01411896.2017.1340033. ISSN 0141-1896. S2CID 148956696.

- ^ a b c Rubin, Joel E. (2020). New York klezmer in the early twentieth century : the music of Naftule Brandwein and Dave Tarras. Rochester, NY: Boydell & Brewer. p. 364. ISBN 9781580465984.

- ^ Horowitz, Josh. "The Main Klezmer Modes". Ari Davidow's Klezmer Shack. Retrieved 24 June 2022.

- ^ Netsky, Hankus (2015). Klezmer: Music and Community in Twentieth-Century Jewish Philadelphia. Philadelphia: Temple University Press. pp. 19–21. ISBN 9781439909034.

- ^ Stutchewsky, Joachim (1959). הכליזמרים : תולדותיהם, אורח-חיים ויצירותיהם (in Hebrew). Jerusalem: Bialik Institute. pp. 29–45.

- ^ Rivkind, Isaac (1960). Pereq be-Toldot Ha-Amanut Ha-'Amamit (in Hebrew). New York: Futuro Press. p. 16.

- ^ Feldman, Zev (2016). Klezmer : music, history and memory. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. pp. 62–63. ISBN 9780190244521.

- ^ Zaagsma, Gerben (2000). "The Klezmorim of Prague: About a Jewish Musicians' Guild". East European Meetings in Ethnomusicology. 7: 41–47.

- ^ Feldman, Zev (2016). Klezmer: music, history and memory. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. pp. 71–73. ISBN 9780190244521.

- ^ Horowitz, Joshua (2012). "9. The Klezmer Accordion". In Simonett, Helena (ed.). The accordion in the Americas : klezmer, polka, tango, zydeco, and more!. Urbana: University of Illinois Press. p. 195. ISBN 9780252094323.

- ^ Stutchewsky, Joachim (1959). הכליזמרים : תולדותיהם, אורח-חיים ויצירותיהם (in Hebrew). Jerusalem: Bialik Institute. pp. 110–114.

- ^ Rubin, Joel (2020). New York klezmer in the early twentieth century : the music of Naftule Brandwein and Dave Tarras. Rochester, NY: Rochester University. p. 28. ISBN 9781580465984.

- ^ Beregovski, Moshe; Rothstein, Robert; Bjorling, Kurt; Alpert, Michael; Slobin, Mark (2020). Jewish instrumental folk music : the collections and writings of Moshe Beregovski (Second ed.). Evanston, Illinois. pp. I7–I9. ISBN 9781732618107.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Feldman, Zev (2016). Klezmer: music, history and memory. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. p. 149. ISBN 9780190244514.

- ^ a b Wollock, Jeffrey (Spring 1997). "European Recordings of Jewish Instrumental Folk Music, 1911–1914". ARSC Journal. 28 (1): 36–55.

- ^ Rubin, Joel; Aylward, Michael (2019). Chekhov's Band: Eastern European Klezmer Music from the EMI archives, 1908–1913 (CD). London: Renair Records.

- ^ Netsky, Hankus (2015). Klezmer: Music and Community in Twentieth-Century Jewish Philadelphia. Philadelphia: Temple University Press. pp. 10–11. ISBN 9781439909034.

- ^ Sholokhova, Lyudmila (2004). "Zinoviy Kiselhof as a Founder of Jewish Musical Folklore Studies in the Russian Empire at the Beginning of the 20th Century.". In Grözinger, Karl-Erich (ed.). Klesmer, Klassik, jiddisches Lied: jüdische Musikkultur in Osteuropa. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. pp. 63–72. ISBN 9783447050319.

- ^ Grözinger, Elvira (2008). "Unser Rebbe, unser Stalin – ": jiddische Lieder aus den St. Petersburger Sammlungen von Moishe Beregowski (1892–1961) und Sofia Magid (1892–1954); Einleitung, Texte, Noten mit DVD: Verzeichnis der gesamten weiteren 416 Titel, Tondokumente der bearbeiteten und nichtbearbeiteten Lieder. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz. pp. 40–3. ISBN 9783447056892.

- ^ Feldman, Zev (2016). Klezmer: music, history and memory. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. p. 24. ISBN 9780190244521.

- ^ Shternshis, Anna (2006). Soviet and kosher : Jewish popular culture in the Soviet Union, 1923–1939. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. pp. xv–xx. ISBN 0253347262.

- ^ Wollock, Jeffrey (Spring 2003). "Soviet Recordings of Jewish Instrumental Folk Music, 1937–1939". ARSC Journal. 34 (1). Annapolis, MD: 14–32.

- ^ Sholokhova, Lyudmila. "Beregovskii, Moisei Iakovlevich". YIVO Encyclopedia. YIVO Institute. Retrieved 8 July 2021.

- ^ Feldman, Zev (2016). Klezmer: music, history and memory. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. p. 129. ISBN 9780190244514.

- ^ Estraikh, Gennady (2008). Yiddish in the Cold War. London: Routledge. p. 57. ISBN 9781351194471.

- ^ Shternshis, Anna (2006). Soviet and kosher: Jewish popular culture in the Soviet Union, 1923–1939. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. pp. 3–4. ISBN 0253347262.

- ^ Rubin, Joel E. (2020). New York klezmer in the early twentieth century : the music of Naftule Brandwein and Dave Tarras. Rochester, NY: Boydell & Brewer. p. 39. ISBN 9781580465984.

- ^ Heskes, Irene (1995). Yiddish American popular songs, 1895 to 1950 : a catalog based on the Lawrence Marwick roster of copyright entries. Washington, D.C.: Library of Congress. pp. xix=xxi. ISBN 0844407453.

- ^ Rubin, Joel E. (2020). New York klezmer in the early twentieth century : the music of Naftule Brandwein and Dave Tarras. Rochester, NY: Boydell & Brewer. p. 36. ISBN 9781580465984.

- ^ a b Loeffler, James (2002). "3: Di Rusishe Progresiv Muzikal Yunyon No. 1 fun Amerike The First Klezmer Union in America". In Slobin, Mark (ed.). American Klezmer : its roots and offshoots. University of California Press. pp. 35–51. ISBN 978-0-520-22717-0.

- ^ Netsky, Hankus (2015). Klezmer: Music and Community in Twentieth-Century Jewish Philadelphia. Philadelphia: Temple University Press. pp. 98–9. ISBN 978-1-4399-0903-4.

- ^ "Columbia Repertoire History: Foreign Language Recordings – Discography of American Historical Recordings". Discography of American Historical Recordings. Retrieved 12 February 2021.

- ^ "The Sounds of Fighting Men, Howlin' Wolf and Comedy Icon Among 25 Named to the National Recording Registry". Library of Congress. Retrieved 13 February 2021.

- ^ Sapoznik, Henry (1999). Klezmer! : Jewish music from Old World to our world. Schirmer Books. p. 68. ISBN 9780028645742.

- ^ Netsky, Hankus. "Fon der Choope (From the Wedding) - Abe Elenkrig's Yidishe Orchestra (April 4, 1913)" (PDF). Library of Congress. Retrieved 19 June 2021.

- ^ Heskes, Irene (1995). Yiddish American popular songs, 1895 to 1950 : a catalog based on the Lawrence Marwick roster of copyright entries. Washington, D.C.: Library of Congress. p. xxxiv. ISBN 0844407453.

- ^ Feldman, Zev (2016). Klezmer: music, history and memory. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. p. 279. ISBN 9780190244514.

- ^ "Lt. Joseph Frankel's Orchestra - Discography of American Historical Recordings". Discography of American Historical Recordings.

- ^ Sapoznik, Henry (1999). Klezmer! : Jewish music from Old World to our world. New York: Schirmer Books. pp. 87–94. ISBN 9780028645742.

- ^ Sapoznik, Henry (2006). Klezmer! : Jewish music from Old World to our world (2nd ed.). New York: Schirmer Trade Books. pp. 107–11. ISBN 9780825673245.

- ^ Wollock, Jeffrey (2007). "Historic Records as Historical Records: Hersh Gross and His Boiberiker Kapelye (1927–1932)" (PDF). ARSC Journal. 38 (1): 44–106.

- ^ Rubin, Joel E. (2020). New York klezmer in the early twentieth century: the music of Naftule Brandwein and Dave Tarras. Rochester, NY: Boydell & Brewer. pp. 260–263. ISBN 9781787448315.

- ^ Sapoznik, Henry (2006). Klezmer! : Jewish music from Old World to our world (2nd ed.). New York: Schirmer Trade Books. pp. 99–109. ISBN 9780825673245.

- ^ Jews and American popular culture. Westport, Conn.: Praeger Publishers. 2007. p. 86. ISBN 9780275987954.

- ^ Rubin, Joel (2020). New York klezmer in the early twentieth century : the music of Naftule Brandwein and Dave Tarras. Rochester, NY: Rochester University. pp. 2–4. ISBN 9781580465984.

- ^ a b Kirshenblatt-Gimblett, Barbara (1998). "Sounds of sensibility". Judaism: A Quarterly Journal of Jewish Life and Thought. 47 (1): 49–79.

- ^ Netsky, Hankus (2015). Klezmer: Music and Community in Twentieth-Century Jewish Philadelphia. Philadelphia: Temple University Press. pp. 4–5. ISBN 9781439909034.

- ^ Slobin, Mark (2000). Fiddler on the move: exploring the klezmer world. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 4. ISBN 9780195161809.

- ^ "Steven Greenman". stevengreenman.com. Retrieved 19 January 2016.

- ^ "Home". klezmers.com.

- ^ "The Other Europeans". other-europeans-band.eu. Archived from the original on 30 April 2011. Retrieved 19 January 2016.

- ^ "The Jerusalem Klezmer Association".

- ^ Out and AboutUpcoming Events·1 min read (20 March 2023). "The annual Safed Klezmer Festival returns to wow the north of Israel!". The ESSENTIAL guide to Israel | iGoogledIsrael.com. Retrieved 24 April 2023.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "Klezmer Festival in Safed". Safed Israel. Retrieved 24 April 2023.

- ^ Rogovoy, S. (2000). The Essential Klezmer. Algonquin Books. p. 71. ISBN 978-1-56512-863-7. Retrieved 1 May 2017.

- ^ "Ofer Ben-Amots: The Klezmer Concerto". Bernstein Artists, Inc. 2006. Archived from the original on 6 June 2014. Retrieved 6 June 2014.

- ^ Ben-Amots, Ofer (2006). Klezmer Concerto. Colorado Springs: The Composer's Own Press. ISBN 978-1-939382-07-8.

- ^ Suris, B. D. (1972). Анатолий Львович Каплан. Anatoliĭ Lʹvovich Kaplan. Leningrad: Khudozhnik RSFSR. pp. 234–236.

- ^ Rubin, Joel; Ottens, Rita (15 May 2000). "A Tickle in the Heart". Archived from the original on 4 April 2009.

- ^ Netsky, Hankus (2015). Klezmer: Music and Community in Twentieth-Century Jewish Philadelphia. Philadelphia: Temple University Press. p. 9. ISBN 9781439909034.

- ^ Feldman, Zev (2016). Klezmer: music, history and memory. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. p. 60. ISBN 9780190244521.

- ^ Heskes, Irene (1995). Yiddish American popular songs, 1895 to 1950 : a catalog based on the Lawrence Marwick roster of copyright entries. Washington, D.C.: Library of Congress. p. xix. ISBN 0844407453.

External links

[edit]- YIVO Encyclopedia article on Traditional and Instrumental Music of Eastern European Jews

- KlezKanada, Yiddish Summer Weimar, Yiddish New York, festivals where klezmer music is taught

- Klezmer Institute, an academic group aiming to study and discuss klezmer

- Yiddish American Popular Sheet Music, a collection of public domain and unpublished scores in the Library of Congress, including the handwritten scores of a number of early American klezmer artists

- Mayrent Collection of Yiddish recordings, an open archive of digitized Yiddish and klezmer recordings

- KlezmerGuide.com. Comprehensive cross-reference to klezmer recordings and sheet music sources

- Klezmer Podcast and Radiant Others Archived 30 March 2022 at the Wayback Machine, two podcasts (currently inactive) which interviewed klezmer performers and scholars

- Stowe, D.W. (2004). How Sweet the Sound: Music in the Spiritual Lives of Americans. Harvard University Press. p. 182. ISBN 9780674012905. Retrieved 9 November 2015.

- Cohen, Bob. "Jewish Music in Romania". Jewish Music in Eastern Europe. Di Naye Kapelye. Retrieved 9 November 2015.