Pearl Primus

Pearl Primus | |

|---|---|

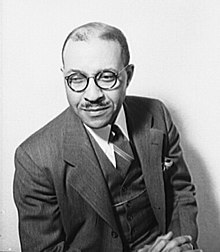

Primus performing "The Negro Speaks of Rivers" in 1944 | |

| Born | November 29, 1919 |

| Died | October 29, 1994 (aged 74) New Rochelle, New York, United States |

| Education | Hunter College New York University |

| Occupation(s) | Choreographer, dancer, anthropologist |

| Spouse | Percival Borde |

| Career | |

| Former groups | New Dance Group |

Pearl Eileen Primus (November 29, 1919 – October 29, 1994) was an American dancer, choreographer and anthropologist. Primus played an important role in the presentation of African dance to American audiences. Early in her career she saw the need to promote African dance as an art form worthy of study and performance. Primus' work was a reaction to myths of savagery and the lack of knowledge about African people. It was an effort to guide the Western world to view African dance as an important and dignified statement about another way of life.[1]

Background

[edit]Born in Port of Spain, Trinidad, Pearl Primus was two years old when she moved with her parents, Edward Primus and Emily Jackson, to New York City in 1921.[2][3] In 1940, Primus received her bachelor's degree from Hunter College[4] in biology and pre-medical science. As a graduate student in biology, she realized that her dreams of becoming a medical researcher would be unfulfilled, due to racial discrimination at the time that imposed limitations on jobs in the science field for people of color. Because of society's limitations, Primus was unable to find a job as a laboratory technician and she could not fund herself through medical school, so she picked up odd jobs.[5] Eventually Primus sought help from the National Youth Administration and they gave her a job working backstage in the wardrobe department for America Dances. Once a spot became available for a dancer, Primus was hired as an understudy, thus beginning her first theatrical experience. She discovered her innate gift for movement, and she was quickly recognized for her abilities. Within a year, Primus auditioned and won a scholarship for the New Dance Group, a left-wing school and performance company located on the Lower East Side of New York City.[6]

Career

[edit]Primus began her formal study of dance with the New Dance Group in 1941, she was the group's first black student. She trained under the group's founders, Jane Dudley, Sophie Maslow, and William Bates. Through this organization, Primus not only gained a foundation for her contemporary technique, but she learned about artistic activism. The New Dance Group's motto was "dance is a weapon of the class struggle", they instilled the belief that dance is a conscious art and those who view it should be impacted.[7] The organization trained dancers like Primus to be aware of the political and social climate of their time. Primus' exposure to this newfound form of activism encouraged the themes of social protest found in her works.

Primus continued to develop her modern dance foundation with several pioneers such Martha Graham, Charles Weidman, Ismay Andrews, and Asadata Dafora.[8] Amongst these influencers, Dafora's influence on Primus has been largely ignored by historians and unmentioned by Primus.[9] However, Marcia Ethel Heard notes that he instilled a sense of African pride in his students and asserts that he taught Primus about African dance and culture.[9] Dafora began a movement of African cultural pride which provided Primus with collaborators and piqued public interest in her work.[10]

Primus explored African culture and dance by consulting family, books, articles, pictures, and museums. After six months of thorough research, she completed her first major composition entitled African Ceremonial. This piece served as an introduction to her swelling interest in Black heritage. She based the dance on a legend from the Belgian Congo, about a priest who performed a fertility ritual until he collapsed and vanished. This thoroughly researched composition was presented along with Strange Fruit, Rock Daniel, and Hard Time Blues, at her debut performance on February 14, 1943, at the 92nd Street YMHA. Her performance was so outstanding that John Martin, a major dance critic from The New York Times stated that "she was entitled to a company of her own."[11] John Martin admired her stage presence, energy, and technique. He described her as a remarkable and distinguished artist.

After gaining much praise, Primus' next performances began in April 1943, as an entertainer at the famous racially integrated night club, Cafe Society Downtown. For 10 months her energy and emotion commanded the stage, along with her stunning five-foot-high jumps. She continued to amaze audiences when she performed at the Negro Freedom Rally, in June 1943, at Madison Square Garden before an audience of 20,000 people.

[10] In December 1943, Primus appeared as in Dafora's African Dance Festival at Carnegie Hall before Eleanor Roosevelt and Mary McLeod Bethune.[12] Within the same month, Primus, who was primarily a solo artist, recruited other dances and formed the Primus Company. The company performed in concerts at the Roxy Theatre. African Ceremonial was re-envisioned for the group's performance. At that time, Primus' African choreography could be termed interpretive, based on the research she conducted and her perception of her findings. Primus would choreograph based on imagining the movement of something she observed, such as an African sculpture.

Over time Primus developed an interest in the way dance represented the lives of people in a culture. Primus was also intrigued by the relationship between the African-slave diaspora and different types of cultural dances.[13] With an enlarged range of interest, Primus began to conduct some field studies. In the summer of 1944, Primus visited the Deep South to research the culture and dances of Southern blacks. She posed as a migrant worker with the aim "to know [her] own people where they are suffering the most."[14] She observed and participated in the daily lives of black impoverished sharecroppers. Primus fully engulfed herself in the experience by attending over seventy churches and picking cotton with the sharecroppers. After her field research, Primus was able to establish new choreography while continuously developing some of her former innovative works.

Primus made her Broadway debut on October 4, 1944, at the Bealson Theatre. Here she performed a work that was choreographed to Langston Hughes' poem "The Negro Speaks of Rivers". The poem addressed the inequalities and injustices imposed on the black community, while introducing comparisons between the ancestry of Black people to four major rivers.[15] Primus' dance to this poem boldly acknowledged the strength and wisdom of African Americans through periods of freedom and enslavement.

In 1945 she continued to develop Strange Fruit (1945) one of the pieces she debuted in 1943. This dance was based on the poem by Lewis Allan about a lynching. When analyzing the dance, one can see that the performer is portraying a female character's reaction after witnessing a lynching. Many viewers wondered about the race of the anguished woman, but Primus declared that the woman was a member of the lynch mob. "The dance begins as the last person begins to leave the lynching ground and the horror of what she has seen grips her, and she has to do a smooth, fast roll away from that burning flesh."[16] Primus depicts the aftermath of the lynching through the remorse of the woman, after she realized the horrible nature of the act. The intention of this piece introduces the idea that even a lynch mob can show penitence.

Primus' work continued to push boundaries as she re-developed another one of her debut pieces, Hard Time Blues (1945). She choreographed this dance to a song by folk singer Josh White. The choreography for this piece, which was made in protest of sharecropping, truly represented Primus' movement style. This piece was embellished with athletic jumps that defied gravity and amazed audiences. But Primus explained that jumping does not always symbolize joy. In this case, her powerful jumping symbolized the defiance, desperation, and anger of the sharecroppers which she experienced first-hand during her field studies. Primus believed that when observing the jumps in the choreography, it was important to pay attention to "the shape the body takes in the air".[17] For Hard Time Blues, the shape of the body was a predictor of the emotional state of the poor sharecroppers.

In 1946, Primus continued her journey on Broadway was invited to appear in the revival of the Broadway production Show Boat, choreographed by Helen Tamiris. Then, she was asked to choreograph a Broadway production called Calypso whose title became Caribbean Carnival. She also appeared at the Chicago Theatre in the 1947 revival of the Emperor Jones in the "Witch Doctor" role that Hemsley Winfield made famous.

In 1947 Primus joined Jacob's Pillow and began her own program in which she reprised some of her works such as Hard Time Blues. In her program she also presented Three Spirituals entitled "Motherless Child", "Goin' to tell God all my Trouble", and "In the Great Gettin'-up Mornin'." These pieces were rooted in Primus' experience with black southern culture. This cannon of Negro spirituals, also referred to as "sorrow songs" branched from slave culture, which at the time was a prominent source of inspiration for many contemporary dance artists.[13]

Following this show and many subsequent recitals, Primus toured the nation with The Primus Company. While on the university and college circuit, Primus performed at Fisk University in 1948, where Dr. Charles S. Johnson, a member of Rosenwald Foundation board, was president. He was so impressed with the power of her interpretive African dances that he asked her when she had last visited Africa. She replied that she had never done so. She then became the last recipient of the major Rosenwald fellowships and received the most money ($4000) ever given. After receiving this funding, Primus originally proposed to develop a dance project based on James Weldon Johnsons work "God's Trombones. But instead she decided to conduct an 18-month research and study tour of the Gold Coast, Angola, Cameroons, Liberia, Senegal and the Belgian Congo.[citation needed] On December 5, 1948, Primus closed a successful return engagement at the Café Society nightclub in New York City before heading off to Africa.[18]

Primus was so well accepted in the communities in her study tour that she was told that the ancestral spirit of an African dancer had manifested in her. The Oni and people of Ife, Nigeria, felt that she was so much a part of their community that they initiated her into their commonwealth and affectionately conferred on her the title "Omowale" — the child who has returned home.[19] During her travels in the villages of Africa, Primus was declared a man so that she could learn the dances only assigned to males. She mastered dances like the war dance Bushasche, and Fanga which were common to African cultural life.

When Primus returned to America, she took the knowledge she gained in Africa and staged pieces for the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theatre. In 1974, Primus staged Fanga created in 1949 which was a Liberian dance of welcome that quickly made its way into Primus's iconic repertoire. She also staged The Wedding created in 1961.[14] These pieces were based on the African rituals Primus experienced during her travels. Primus took these traditionally long rituals, dramatized them, made them shorter, and preserved the foundation of the movement .

Primus learned a plethora in Africa, but she was still eager to further her academic knowledge, Primus received her PhD in anthropology from New York University (NYU) in 1978. In 1979, she and her husband Percival Borde, whom she met during her research in Trinidad, founded the Pearl Primus "Dance Language Institute" in New Rochelle, New York, where they offered classes that blended African-American, Caribbean, and African dance forms with modern dance and ballet techniques. They also established a performance group was called "Earth Theatre".[20]

As an artist/ educator, Primus taught at a number of universities during her career including NYU, Hunter College, the State University of New York at Purchase, the College of New Rochelle, Iona College, the State University of New York at Buffalo, Howard University, the Five Colleges consortium in Massachusetts. She also taught at New Rochelle High School, assisting with cultural presentations.[21] As an anthropologist, she conducted cultural projects in Europe, Africa and America for such organizations as the Ford Foundation, US Office of Education, New York University, Universalist Unitarian Service Committee, Julius Rosenwald Foundation, New York State Office of Education, and the Council for the Arts in Westchester.

Legacy

[edit]Pioneer of African dance in the United States

[edit]Primus' sojourn to West Africa has proven invaluable to students of African dance. She learned more about African dance, its function and meaning than had any other American before her. Primus was known as a griot, the voice of cultures in which dance is embedded. She was able to codify the technical details of many of the African dances through the notation system she evolved and was also able to view and to salvage some "still existent gems of dances before they faded into general decadence."[22] She has been unselfish in sharing the knowledge she has gained with others.[1]

The significance of Primus' African research and choreography lies in her presentation of a dance history which embraces ethnic unity, the establishment of an articulate foundation for influencing future practitioners of African dance, the presentation of African dance forms into a disciplined expression, and the enrichment of American theater through the performance of African dance.[19][23]

Additionally, Primus and the late Percival Borde, her husband and partner, conducted research with the Liberian Konama Kende Performing Arts Center to establish a performing arts center, and with a Rebekah Harkness Foundation grant to organize and direct dance performances in several counties during the period of 1959 to 1962. Primus and Borde taught African dance artists how to make their indigenous dances theatrically entertaining and acceptable to the western world, and also arranged projects between African countries such as Senegal, Gambia, Guinea and the United States Government to bring touring companies to this country.[24]

Choreography approach and style

[edit]Primus' approach to developing a movement language and to creating dance works parallels that of Graham, Holm, Weidman, Agnes de Mille and others who are considered to be pioneers of American modern dance. These artists searched literature, used music of contemporary composers, glorified regional idiosyncrasies and looked to varied ethnic groups for potential sources of creative material.

Primus, however, found her creative impetus in the cultural heritage of the African American. She gained a lot of information from her family who enlightened her about their West Indian roots and African lineage. The stories and memories told to young Pearl, established a cultural and historical heritage for her and laid the foundation for her creative works.[13] Primus' extensive field studies in the South and in Africa was also a key resource for her. She made sure to preserve the traditional forms of expression that she observed. In this way she differed from other dance groups who altered the African dances that they incorporated into their movements. Her view of "dance as a form of life" supported her decision to keep her choreography real and authentic.[25]

Primus fused spirituals, jazz and blues, then coupled these music forms with the literary works of black writers, and her choreographic voice — though strong — resonated primarily for and to the black community. Her many works 'Strange Fruit', Negro Speaks of Rivers, Hard Time Blues, and more spoke on very socially important topics. Her creative endeavors in political and social change makes Primus arguably one of the most political choreographers of her time because of her awareness of the issues of African Americans, particularly during the period between World War I and II.[26]

Primus was a powerhouse dancer, whose emotions, exuberance, and five-foot-high athletic jumps wowed every audience she performed for. Her performance of Hard Time Blues was described by Margaret Lloyd: "Pearl takes a running jump, lands in an upper corner and sits there, unconcernedly paddling the air with her legs. She does it repeatedly, from one side of the stage, then the other, apparently unaware of the involuntary gasps from the audience...."[27] Primus' athleticism made her choreography awe-striking. She preserved traditional movements but added her own style which includes modified pelvic rotations and rhythmic variations. As she moved Primus carried intensity and displayed passion while simultaneously bringing awareness to social issues.

Primus' strong belief that rich choreographic material lay in abundance in the root experiences of a people has been picked up and echoed in the rhythm and themes of Alvin Ailey, Donald McKayle, Talley Beatty, Dianne McIntyre, Elo Pomare and others. Her work has also been reimagined and recycled into different versions by contemporary artists. Many choreographers, such as Jawolle Willa Jo Zollar, created projects inspired by Primus' work. Primus choreography which included bent knees, the isolation and articulation of body parts, and rhythmically percussive movement, can be observed in the movement of Zollar and many others.[13] These similarities show that Primus' style, themes, and body type promoted the display of Black culture within the dance community.

Personal life and death

[edit]Pearl married Yael Woll in 1950, Manhattan, New York.[28] They were divorced by 1957.

Primus married the dancer, drummer, and choreographer Percival Borde in 1961,[29] and began a collaboration that ended only with his death in 1979. In 1959, the year Primus received an M.A. in education from New York University, she traveled to Liberia, where she worked with the National Dance Company there to create Fanga, an interpretation of a traditional Liberian invocation to the earth and sky.[30]

Primus believed in sound research. Her meticulous search of libraries and museums and her use of living source materials established her as a dance scholar.[1]

Primus focused on matters such as oppression, racial prejudice, and violence. Her efforts were also subsidized by the United States government who encouraged African-American artistic endeavors.

Primus died from diabetes at her home in New Rochelle, New York, on October 29, 1994.[31]

Recognition

[edit]In 1991, President George H. W. Bush honored Primus with the National Medal of Arts.[32] She was the recipient of numerous other honors including: The cherished Liberian Government Decoration, "Star of Africa"; The Scroll of Honor from the National Council of Negro Women; The Pioneer of Dance Award from the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theatre; Membership in Phi Beta Kappa; an honorary doctorate from Spelman College; the first Balasaraswati/ Joy Ann Dewey Beinecke Chair for Distinguished Teaching at the American Dance Festival; The National Culture Award from the New York State Federation of Foreign Language Teachers; Commendation from the White House Conference on Children and Youth.[1]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d Myers, Gerald E. (1993). African American Genius in Modern Dance. Durham, N.C.: American Dance Festival.

- ^ Gloria Grant Roberson, "Primus, Pearl Eileen", The Scribner Encyclopedia of American Lives. Encyclopedia.com.

- ^ "Pearl Primus", Encyclopædia Britannica.

- ^ "Alumni". Flickr. Retrieved 2018-07-31.

- ^ Mennenga, Lacinda (2008-06-30). "Pearl Primus (1919-1994) • BlackPast". BlackPast. Retrieved 2019-12-08.

- ^ Green, Richard C. (2002). "(Up)Staging the Primitive: Pearl Primus and 'the Negro Problem' in American Dance". In DeFrantz, Thomas F. (ed.). Dancing Many Drums: Excavations in African American Dance. Madison, Wisconsin: University of Wisconsin Press. ISBN 0299173143.

- ^ "The New Dance Group: Transforming Individuals and Community". dancetimepublications.com. Retrieved 2019-12-08.

- ^ Heard 1999, p. 181.

- ^ a b Heard 1999, p. 181–184.

- ^ a b Heard 1999, p. 184–187.

- ^ Martin, John (1943-02-21). "THE DANCE: FIVE ARTISTS; Second Annual Joint Recital Project of the Y.M.H.A. -- Week's Programs". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2019-12-08.

- ^ Heard 1999, p. 183–187.

- ^ a b c d "Pearl Primus". Jacob's Pillow Dance Interactive. Retrieved 2019-12-09.

- ^ a b "Dance History: Pearl Primus". Dance Teacher. 2009-03-16. Retrieved 2019-12-09.

- ^ ericagreil (2011-03-09). "Langston Hughes, "The Negro Speaks of Rivers"". Blog@BBF. Retrieved 2019-12-09.

- ^ "Pearl Primus in "Strange Fruit"". The New York Public Library. Retrieved 2019-12-09.

- ^ Lloyd, Margaret (1949). The Borzoi Book of Modern Dance. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, Znc. ISBN 0-87127-275-X.

- ^ "The Dance: Chitchat". The New York Times. December 5, 1948. p. X10.

- ^ a b Creque Harris, Leah (1991). The Representation of African Dance on the Stage: From the early black musical to Pearl Primus. Atlanta, GA: Emory University.

- ^ Primus, Pearl (1950). Earth Theatre. Theater Arts.

- ^ "Dance As A Language", Dance: A Tribute to Pearl E. Primus.

- ^ Primus, from the Schomburg Library: Primus File, 1949

- ^ Hering, Doris (1950). "Little Fast Feet: The Story of the Pilgrimage of Pearl Primus to Africa". Dance Magazine.

- ^ Martin, John (July 31, 1966). The New York Times.

- ^ "Dr. Pearl Primus, choreographer, dancer and anthropologist". amsterdamnews.com. 27 December 2018. Retrieved 2019-12-09.

- ^ "Dances of Sorrow, Dances of Hope : The work of Pearl Primus finds a natural place in a special program of historic modern dances for women. Primus' 1943 work 'Strange Fruit' leaped over the boundaries of what was then considered 'black dance'". Los Angeles Times. 1994-04-24. Retrieved 2019-12-09.

- ^ "The Borzoi Book of Modern Dance - PDF Free Download". epdf.pub. Retrieved 2019-12-09.

- ^ "New York, New York City Marriage Licenses Index, 1950-1995". database, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:QLSR-V3TM : 19 June 2017), Yael Woll and Pearl Primus, 1950, Manhattan, New York City, New York.

- ^ "New York, New York City Marriage Licenses Index, 1950-1995," database, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:QLS5-YS1P : 19 June 2017), Percival Borde and Pearl Woll, 1961

- ^ McPherson, Elizabeth. "Pearl Primus". Dance Teacher Magazine. Archived from the original on 2012-06-23. Retrieved 2012-05-08.

- ^ Dunning, Jennifer (October 31, 1994). "Obituary - Pearl Primus". The New York Times. Retrieved May 8, 2012.

- ^ Dunning, Jennifer (31 October 1994). "Pearl Primus Is Dead at 74; A Pioneer of Modern Dance". The New York Times. Retrieved 2018-07-31.

Sources

[edit]- Heard, Marcia Ethel (1999). Asadata Dafora: African Concert Dance Traditions in American Concert Dance (Ph.D.). New York University, School of Education. Retrieved 9 October 2017.

- Schwartz, Peggy and Murray (2012). The Dance Claimed Me: A Biography of Pearl Primus. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

- "Black America- Dance of the Spirit". Focus on Dance. November 6, 1972.

- Sorrell, Walter (1966). "Out of Africa" in The Dance Has Many Faces. New York: Columbia Press.

- DeFrantz, Thomas (2002). Dancing Many Drums: Excavations in African American Dance. Madison, Wis: University of Wisconsin Press.

- Fauley Emery, Lynne (1989). Black Dance: From 1619 to Today. Princeton Book Company.

- Lloyd, Margaret (1987). The Borzoi Book of Modern Dance. Princeton Book Company.

- Foulkes, Julia L. (2002). Modern Bodies: Dance and American Modernism. University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 9780807853672.

External links

[edit]- Picture of Pearl Primus in Folk Dance (1945)

- Archive footage of Primus performing Spirituals in 1950 at Jacob's Pillow

- Anna Kisselgoff, "Pearl Primus rejoices in the Black tradition", The New York Times, June 19, 1988.

- mamboso.com

- 1919 births

- 1994 deaths

- 20th-century African-American scientists

- 20th-century African-American women

- 20th-century American anthropologists

- 20th-century American dancers

- African-American anthropologists

- African-American choreographers

- African-American dancers

- African-American female dancers

- American choreographers

- American female dancers

- American women anthropologists

- American women choreographers

- Artists from New Rochelle, New York

- Dancers from New York (state)

- Hunter College alumni

- Hunter College High School alumni

- American modern dancers

- People from Port of Spain

- Steinhardt School of Culture, Education, and Human Development alumni

- Trinidad and Tobago choreographers

- Trinidad and Tobago dancers

- Trinidad and Tobago emigrants to the United States

- Trinidad and Tobago people of Ashanti descent

- Trinidad and Tobago people of Ghanaian descent

- Trinidad and Tobago women choreographers

- United States National Medal of Arts recipients

- African-American women choreographers