Zimmermann telegram

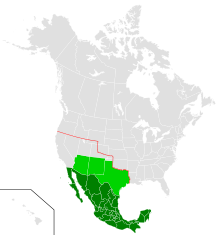

The Zimmermann telegram (or Zimmermann note or Zimmermann cable) was a secret diplomatic communication issued from the German Foreign Office in January 1917 that proposed a military contract between the German Empire and Mexico if the United States entered World War I against Germany. With Germany's aid, Mexico would recover Texas, Arizona, and New Mexico. The telegram was intercepted by British intelligence.

Revelation of the contents enraged Americans, especially after German State Secretary for Foreign Affairs Arthur Zimmermann publicly admitted on March 3, 1917, that the telegram was genuine. It helped to generate support for the American declaration of war on Germany in April 1917.[1]

The decryption has been described as the most significant intelligence triumph for Britain during World War I[2] and it marked one of the earliest occasions on which a piece of signals intelligence influenced world events.[3] The decryption was possible after the failure of the Niedermayer-Hentig Expedition to Afghanistan, when Wilhelm Wassmuss abandoned his codebook, which the Allies later recovered, and allowed the British to decrypt the Zimmermann telegram.[4]

Content

[edit]

The message came in the form of a coded telegram dispatched by Arthur Zimmermann, the Staatssekretär (a top-level civil servant, second only to their respective minister) in the Foreign Office of the German Empire on January 17, 1917. The message was sent to the German ambassador to Mexico, Heinrich von Eckardt.[5] Zimmermann sent the telegram in anticipation of the resumption of unrestricted submarine warfare by Germany on February 1, which the German government presumed would almost certainly lead to war with the United States. The telegram instructed Von Eckardt that if the United States appeared certain to enter the war, he was to approach the Mexican government with a proposal for military alliance with funding from Germany. The decoded telegram was as follows:[6]

Original (German):

Wir beabsichtigen am 1. Februar uneingeschränkten Ubootkrieg zu beginnen. Es wird Versucht werden, Amerika trotzdem neutral zu halten.

Für den Fall, daß dies nicht gelingen sollte, schlagen wir Mexico mit folgender Grundlage Bündnis vor; Gemeinsame Kriegführung, gemeinsamer Friedensschluß. Reichliche finzanzielle Unterstützung und Einverständnis unsererseits, daß Mexiko in Texas, Neu Mexiko, Arizona früher verlorenes Gebiet zurückerobert. Regelung im einzelnen Euer Hochwohlgeboren überlassen.

Euer pp. wollen Vorstehendes Präsidenten streng geheim eröffnen, sobald Kriegsausbruch mit Vereinigten Staaten feststeht und Anregung hinzufügen, Japan von sich aus zu fortigem Beitritt einzuladen und gleichzeitig zwischen uns und Japan zu vermitteln.

Bitte Präsidenten darauf hinweisen, daß rücksichtslose Anwendung unserer U-boote jetzt Aussicht bietet, England in wenigen Monaten zum Frieden zu zwingen. Empfang bestätigen.

Zimmerman.[7]

Translated:

On February 1 we intend to begin submarine warfare without restriction. In spite of this it is our intention to endeavour to keep the United States neutral. If this attempt is not successful, we propose an alliance on the following basis with Mexico:

That we shall make war together and together make peace; we shall give general financial support, and it is understood that Mexico is to reconquer her lost territory of New Mexico, Texas and Arizona. The details are left to you for settlement.

You are instructed to inform the President of Mexico of the above in the greatest confidence as soon as it is certain that there will be an outbreak of war with the United States, and suggest that the President of Mexico shall on his own initiative communicate with Japan suggesting the latter's adherence at once to this plan, and at the same time offer to mediate between Germany and Japan.

Please call to the attention of the President of Mexico that the employment of ruthless submarine warfare now promises to compel England to make peace in a few month [sic]. – Zimmerman.[7]

(The signature dropped the second n of the name Zimmermann for telegraphic purposes.[7])

History

[edit]Previous German efforts to promote war

[edit]Germany had long sought to incite a war between Mexico and the United States, which would have tied down American forces and slowed the export of American arms to the Allies.[8] The Germans had aided in arming Mexico, as shown by the 1914 Ypiranga incident.[9] German Naval Intelligence officer Franz von Rintelen had attempted to incite a war between Mexico and the United States in 1915, giving Victoriano Huerta $12 million for that purpose.[10] The German saboteur Lothar Witzke, who was based in Mexico City, claimed to be responsible for the March 1917 munitions explosion at the Mare Island Naval Shipyard in the San Francisco Bay Area,[11] and was possibly responsible for the July 1916 Black Tom explosion in New Jersey.

The failure of United States troops to capture Pancho Villa in 1916 and the movement of President Carranza in favor of Germany emboldened the Germans to send the Zimmermann note.[12]

The German provocations were partially successful. President Woodrow Wilson ordered the military invasion of Veracruz in 1914 in the context of the Ypiranga incident and against the advice of the British government.[13] War was prevented thanks to the Niagara Falls peace conference organized by the ABC nations, but the occupation was a decisive factor in Mexican neutrality in World War I.[14] Mexico refused to participate in the embargo against Germany and granted full guarantees to the German companies for keeping their operations open, specifically in Mexico City.[15]

German motivations

[edit]

The Zimmermann telegram was part of an effort carried out by the Germans to postpone the transportation of supplies and other war materials from the United States to the Allies, which were at war against Germany.[17] The main purpose of the telegram was to make the Mexican government declare war on the United States in hopes of tying down American forces and slowing the export of American arms.[18] The German High Command believed that it could defeat the British and French on the Western Front and strangle Britain with unrestricted submarine warfare before American forces could be trained and shipped to Europe in sufficient numbers to aid the Allies. The Germans were encouraged by their successes on the Eastern Front to believe that they could divert large numbers of troops to the Western Front in support of their goals.[citation needed]

Mexican response

[edit]Mexican President Venustiano Carranza assigned a military commission to assess the feasibility of the Mexican takeover of their former territories contemplated by Germany.[19] The generals concluded that such a war was unwinnable for the following reasons:

- Mexico was in the midst of a civil war, and Carranza's position was far from secure. (Carranza himself was later assassinated in 1920.) Picking a fight with the United States would have prompted the U.S. to support one of his rivals.

- The United States was far stronger militarily than Mexico was. Even if Mexico's military forces had been completely united and loyal to a single government, no serious scenario existed under which it could have invaded and won a war against the United States. Indeed, much of Mexico's military hardware of 1917 reflected only modest upgrades since the Mexican-American War 70 years before, which the U.S. had won.

- The German government's promises of "generous financial support" were very unreliable. It had already informed Carranza in June 1916 that it could not provide the necessary gold needed to stock a completely independent Mexican national bank.[20] Even if Mexico received financial support, it would still need to purchase arms, ammunition, and other needed war supplies from the ABC nations (Argentina, Brazil, and Chile), which would strain relations with them, as explained below.

- Even if by some chance Mexico had the military means to win a conflict against the United States and to reclaim the territories in question, it would have had severe difficulty conquering and pacifying a large English-speaking population which had long enjoyed self-government and was better supplied with arms than were most other civilian populations.[19]

- Other foreign relations were at stake. The ABC nations had organized the Niagara Falls peace conference in 1914 to avoid a full-scale war between the United States and Mexico over the United States occupation of Veracruz. Mexico entering a war against the United States would strain relations with those nations.

The Carranza government was recognized de jure by the United States on August 31, 1917, as a direct consequence of the Zimmermann telegram to ensure Mexican neutrality during World War I.[21][22] After the military invasion of Veracruz in 1914, Mexico did not participate in any military excursion with the United States in World War I.[14] That ensured that Mexican neutrality was the best outcome that the United States could hope for even if it allowed German companies to keep their operations in Mexico open.[15]

British interception

[edit]

The decryption was possible after the failure of the Niedermayer-Hentig Expedition to Afghanistan, when Wilhelm Wassmuss abandoned his codebook, which the Allies later recovered, and allowed the British to decrypt the Zimmermann telegram.[23]

Zimmermann's office sent the telegram to the German embassy in the United States for retransmission to Von Eckardt in Mexico. It has traditionally been understood that the telegram was sent over three routes. It went by radio, and passed via telegraph cable inside messages sent by diplomats of two neutral countries (the United States and Sweden).

Direct telegraph transmission of the telegram was impossible because the British had cut the German international cables at the outbreak of war. However, Germany could communicate wirelessly through the Telefunken plant, operating under Atlantic Communication Company in West Sayville, New York, where the telegram was relayed to the Mexican Consulate. Ironically, the station was under the control of the US Navy, which operated it for Atlantic Communication Company, the American subsidiary of the German entity.

The Swedish diplomatic message holding the Zimmerman telegram went from Stockholm to Buenos Aires over British submarine telegraph cables, and then moved from Buenos Aires to Mexico over the cable network of a United States company.

After the Germans' telegraph cables had been cut, the German Foreign Office appealed to the United States for use of their diplomatic telegraphic messages for peace messages. President Wilson agreed in the belief both that such co-operation would sustain continued good relations with Germany and that more efficient German–American diplomacy could assist Wilson's goal of a negotiated end to the war. The Germans handed in messages to the American embassy in Berlin, which were relayed to the embassy in Denmark and then to the United States by American telegraph operators. The Germans assumed that this route was secure and so used it extensively.[24]

However, that put German diplomats in a precarious situation since they relied on the United States to transmit Zimmermann's note to its final destination, but the message's unencrypted contents would be deeply alarming to the Americans. The United States had placed conditions on German usage, most notably that all messages had to be in cleartext (uncoded). However, Wilson had later reversed the order and relaxed the wireless rules to allow coded messages to be sent.[25] Thus the Germans were able to persuade US Ambassador James W. Gerard to accept Zimmermann's note in coded form, and it was transmitted on January 16, 1917.[24]

All traffic passing through British hands came to British intelligence, particularly to the codebreakers and analysts in Room 40 at the Admiralty.[24] In Room 40, Nigel de Grey had partially decoded the telegram by the next day.[26] By 1917, the diplomatic code 13040 had been in use for many years. Since there had been ample time for Room 40 to reconstruct the code cryptanalytically, it was readable to a fair degree. Room 40 had obtained German cryptographic documents, including the diplomatic code 3512 (captured during the Mesopotamian campaign), which was a later updated code that was similar to but not really related to code 13040, and naval code SKM (Signalbuch der Kaiserlichen Marine), which was useless for decoding the Zimmermann telegram but valuable to decode naval traffic, which had been retrieved from the wrecked cruiser SMS Magdeburg by the Russians, who passed it to the British.[27]

Disclosure of the telegram would sway American public opinion against Germany if the British could convince the Americans that the text was genuine, but the Room 40 chief William Reginald Hall was reluctant to let it out because the disclosure would expose the German codes broken in Room 40 and British eavesdropping on United States diplomatic traffic. Hall waited three weeks during which de Grey and cryptographer William Montgomery completed the decryption. On February 1, Germany announced resumption of "unrestricted" submarine warfare, an act that led the United States to break off diplomatic relations with Germany on February 3.[24]

Hall passed the telegram to the British Foreign Office on February 5 but still warned against releasing it. Meanwhile, the British discussed possible cover stories to explain to the Americans how they obtained the coded text of the telegram and to explain how they obtained the cleartext of the telegram without letting anyone know that the codes had been broken. Furthermore, the British needed to find a way to convince the Americans the message was not a forgery.[28]

For the first story, the British obtained the coded text of the telegram from the Mexican commercial telegraph office. The British knew that since the German embassy in Washington would relay the message by commercial telegraph, the Mexican telegraph office would have the coded text. "Mr. H", a British agent in Mexico, bribed an employee of the commercial telegraph company for a copy of the message. Sir Thomas Hohler, the British ambassador in Mexico, later claimed to have been "Mr. H" or at least to have been involved with the interception in his autobiography.[29] The coded text could then be shown to the Americans without embarrassment.

Moreover, the retransmission was encoded with the older code 13040 and so by mid-February, the British had the complete text and the ability to release the telegram without revealing the extent to which the latest German codes had been broken. (At worst, the Germans might have realized that the 13040 code had been compromised, but that was a risk worth taking against the possibility of United States entry into the war.) Finally, since copies of the 13040 code text would also have been deposited in the records of the American commercial telegraph company, the British had the ability to prove the authenticity of the message to the American government.[3]

As a cover story, the British could publicly claim that their agents had stolen the telegram's decoded text in Mexico. Privately, the British needed to give the Americans the 13040 code so that the American government could verify the authenticity of the message independently with their own commercial telegraphic records, but the Americans agreed to back the official cover story. The German Foreign Office refused to consider that their codes could have been broken but sent Von Eckardt on a witch hunt for a traitor in the embassy in Mexico. Von Eckardt indignantly rejected those accusations, and the Foreign Office eventually declared the embassy exonerated.[24]

Use

[edit]On February 19, Hall showed the telegram to Edward Bell, the secretary of the American Embassy in Britain. Bell was at first incredulous and thought that it was a forgery. Once Bell was convinced the message was genuine, he became enraged. On February 20, Hall informally sent a copy to US Ambassador Walter Hines Page. On February 23, Page met with British Foreign Minister Arthur Balfour and was given the codetext, the message in German, and the English translation. The British had obtained a further copy in Mexico City, and Balfour could obscure the real source with the half-truth that it had been "bought in Mexico".[30] Page then reported the story to Wilson on February 24, 1917, including details to be verified from telegraph-company files in the United States. Wilson felt "much indignation" toward the Germans and wanted to publish the Zimmermann Telegraph immediately after he had received it from the British, but he delayed until March 1, 1917.[31]

U.S. response

[edit]

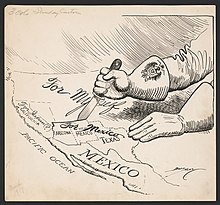

Many Americans then held anti-Mexican as well as anti-German views. Mexicans had a considerable amount of anti-American sentiment in return, some of which was caused by the American occupation of Veracruz.[32] General John J. Pershing had long been chasing the revolutionary Pancho Villa for raiding into American territory and carried out several cross-border expeditions. News of the telegram further inflamed tensions between the United States and Mexico.

However, many Americans, particularly those with German or Irish ancestry, wished to avoid the conflict in Europe. Since the public had been told falsely that the telegram had been stolen in a decoded form in Mexico, the message was at first widely believed to be an elaborate forgery created by British intelligence. That belief, which was not restricted to pacifist and pro-German lobbies, was promoted by German and Mexican diplomats alongside some antiwar American newspapers, especially those of the Hearst press empire.

On February 1, 1917, Germany began unrestricted submarine warfare against all ships in the Atlantic bearing the American flag, both passenger and merchant ships. Two ships were sunk in February, and most American shipping companies held their ships in port. Besides the highly-provocative war proposal to Mexico, the telegram also mentioned "ruthless employment of our submarines". Public opinion demanded action. Wilson had refused to assign US Navy crews and guns to the merchant ships, but once the Zimmermann note was public, Wilson called for arming the merchant ships although antiwar members of the US Senate blocked his proposal.[33]

The Wilson administration nevertheless remained with a dilemma. Evidence the United States had been provided confidentially by the British informed Wilson that the message was genuine, but he could not make the evidence public without compromising the British codebreaking operation. This problem was, however, resolved when any doubts as to the authenticity of the telegram were removed by Zimmermann himself. At a press conference on March 3, 1917, he told an American journalist, "I cannot deny it. It is true." Then, on March 29, 1917, Zimmermann gave a speech in the Reichstag in which he admitted that the telegram was genuine.[34] Zimmermann hoped that Americans would understand that the idea was that Germany would not fund Mexico's war with the United States unless the Americans joined World War I. Nevertheless, in his speech Zimmermann questioned how the Washington government obtained the telegram.[35] According to Reuters news service, Zimmermann told the Reichstag, "the instructions...came into its hands in a way which was not unobjectionable."[35]

On April 6, 1917, Congress voted to declare war on Germany. Wilson had asked Congress for "a war to end all wars" that would "make the world safe for democracy".[36]

Wilson considered another military invasion of Veracruz and Tampico in 1917–1918,[37][38] to pacify the Isthmus of Tehuantepec and Tampico oil fields and to ensure their continued production during the civil war,[38][39] but this time, Mexican President Venustiano Carranza, recently installed, threatened to destroy the oil fields if the US Marines landed there.[40][41]

Japanese response

[edit]The Japanese government, another nation mentioned in the Zimmerman telegram, was already involved in World War I, on the side of the Allies against Germany. The government later released a statement that Japan was not interested in changing sides or attacking America.[42][43]

Autograph discovery

[edit]This section needs to be updated. The reason given is: the six "closed" files may now be "open". (August 2024) |

In October 2005, it was reported that an original typescript of the decoded Zimmermann telegram had recently been discovered by an unnamed historian who was researching and preparing a history of the United Kingdom's Government Communications Headquarters. The document is believed to be the actual telegram shown to the American ambassador in London in 1917. Marked in Admiral Hall's handwriting at the top of the document are the words: "This is the one handed to Dr Page and exposed by the President." Since many of the secret documents in this incident had been destroyed, it had previously been assumed that the original typed "decrypt" was gone forever. However, after the discovery of this document, the GCHQ official historian said: "I believe that this is indeed the same document that Balfour handed to Page."[44]

As of 2006, there were six "closed" files on the Zimmermann telegram which had not been declassified held by The National Archives at Kew (formerly the PRO).[45]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Andrew, Christopher (1996). For The President's Eyes Only. Harper Collins. p. 42. ISBN 0-00-638071-9.

- ^ Why was the Zimmermann Telegram so important? Gordon Corera BBC News 17 January 2017

- ^ a b "The telegram that brought America into the First World War". BBC History Magazine. January 17, 2017. Retrieved January 17, 2017 – via History Extra.

- ^ Hughes, Thomas L. (October 2002), "The German Mission to Afghanistan, 1915–1916", German Studies Review, 25 (3), German Studies Association: 455–456, doi:10.2307/1432596, ISSN 0149-7952, JSTOR 1432596

- ^ "Washington Exposes Plot" (PDF). The Associated Press. Washington. February 28, 1917. Retrieved January 11, 2020.

- ^ Alexander, Mary; Childress, Marilyn (April 1981). "The Zimmermann Telegram". National Archives and Records Administration. Retrieved April 8, 2023. This NARA publication paraphrases a book chapter by the cited authors

- ^ a b c "The Zimmermann Telegram" (PDF). National Security Agency. Retrieved May 24, 2024.

- ^ Katz, Friedrich (1981). The Secret War in Mexico: Europe, the United States, and the Mexican Revolution. pp. 328–329.

- ^ Katz (1981), pp. 232–240.

- ^ Katz (1981), pp. 329–332.

- ^ Tucker, Spencer & Roberts, Priscilla Mary (2005). World War One. Santa Barbara CA: ABC-CLIO. p. 1606. ISBN 1-85109-420-2.

- ^ Katz (1981), pp. 346–347.

- ^ Small, Michael (2009). The Forgotten Peace: Mediation at Niagara Falls, 1914. Ottawa, Canada: University of Ottawa. p. 35. ISBN 9780776607122.

- ^ a b Stacy, Lee (2002). Mexico and the United States, Volume 3. USA: Marshall Cavendish. p. 869. ISBN 9780761474050.

- ^ a b Buchenau, Jürgen (2004). Tools of Progress: A German Merchant Family in Mexico City, 1865–Present. USA: University of New Mexico Press. p. 82. ISBN 9780826330888.

- ^ "The Mexican Telegraph Company – The Zimmermann Telegram – Galveston County ~ Number: 18753". Texas Historic Sites Atlas. Texas Historical Commission. 2017.

- ^ Tuchman, Barbara W. (1958). The Zimmerman Telegram. Random House Publishing. pp. 63, 73–74. ISBN 0-345-32425-0.

- ^ Katz (1981), pp. 328–329.

- ^ a b Katz (1981), p. 364.

- ^ Beezley, William; Meyer, Michael (2010). The Oxford History of Mexico. UK: Oxford University Press. p. 476. ISBN 9780199779932.

- ^ Paterson, Thomas; Clifford, J. Garry; Brigham, Robert; Donoghue, Michael; Hagan, Kenneth (2010). American Foreign Relations, Volume 1: To 1920. USA: Cengage Learning. p. 265. ISBN 9781305172104.

- ^ Paterson, Thomas; Clifford, John Garry; Hagan, Kenneth J. (1999). American Foreign Relations: A History Since 1895. USA: Houghton Mifflin College Division. p. 51. ISBN 9780395938874.

- ^ Hughes, Thomas L. (October 2002), "The German Mission to Afghanistan, 1915–1916", German Studies Review, 25 (3), German Studies Association: 455–456, doi:10.2307/1432596, ISSN 0149-7952, JSTOR 1432596

- ^ a b c d e West, Nigel (1990). The Sigint Secrets: The Signals Intelligence War, 1990 to Today-Including the Persecution of Gordon Welchman. New York: Quill. pp. 83, 87–92. ISBN 0-688-09515-1.

- ^ The New York Times, September 4, 1914

- ^ Gannon, Paul (2011). Inside Room 40: The Codebreakers of World War I. London: Ian Allan Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7110-3408-2.

- ^ Polmar, Norman & Noot, Jurrien (1991). Submarines of the Russian and Soviet Navies 1718–1990. Annapolis: US Naval Institute Press.

- ^ "Why was the Zimmerman Telegram so important?". BBC. January 17, 2017. Retrieved January 17, 2017.

- ^ "Intelligence Insight No. 004 podcast at 44:14 minutes". bletchleypark.org.uk. The Bletchley Park Trust. Retrieved January 5, 2021.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Stevenson, D. (David), 1954- (2017). 1917 : war, peace, and revolution (First ed.). Oxford. p. 59. ISBN 978-0-19-870238-2. OCLC 982092927.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Stevenson, D. (David), 1954- (2017). 1917 : war, peace, and revolution (First ed.). Oxford. p. 59. ISBN 978-0-19-870238-2. OCLC 982092927.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Link, Arthur S. (1965). Wilson: Campaigns for Progressivism and Peace: 1916–1917.

- ^ Leopold, Richard W (1962). The Growth of American Foreign Policy: A History. Random House. pp. 330–31.

- ^ anonymous (April 1917). "The Alliance with Mexico and Japan Proposed by Germany". Current History. 6 (1): 66f. JSTOR 45328280 – via JSTOR.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ a b "Dr. Zimmermannes Defense of His Mexican Plan". Current History. 6 (2): 236–237. 1917. ISSN 2641-080X. JSTOR 45328328.

- ^ Link, Arthur S. (1972). Woodrow Wilson and the Progressive Era, 1910–1917. New York: Harper & Row. pp. 252–282.

- ^ Gruening, Ernest (1968). Mexico and Its Heritage. U.S.: Greenwood Press. p. 596. ISBN 9780837104577.

- ^ a b Halevy, Drew Philip (2000). Threats of Intervention: U. S.-Mexican Relations, 1917–1923. U.S.: iUniverse. p. 41. ISBN 9781469701783.

- ^ Meyer, Lorenzo (1977). Mexico and the United States in the Oil Controversy, 1917–1942. U.S.: University of Texas Press. p. 45. ISBN 9780292750326.

- ^ Haber, Stephen; Maurer, Noel; Razo, Armando (2003). The Politics of Property Rights: Political Instability, Credible Commitments, and Economic Growth in Mexico, 1876–1929. UK: Cambridge University Press. p. 201. ISBN 9780521820677.

- ^ Meyer, Lorenzo (1977), p. 44

- ^ Lee, Roger. "Zimmerman Telegram: What Was The Zimmerman Telegram, and How Did It Affect World War One?". The History Guy. Retrieved July 27, 2018.

- ^ "The Ambassador in Japan to the Secretary of State [Telegram]". Foreign Relations of the United States. March 3, 1917. Retrieved March 19, 2024.

- ^ Fenton, Ben (October 17, 2005). "Telegram that brought US into Great War is Found Found". The Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on September 15, 2012.

- ^ Gannon, Paul (2006). Colossus: Bletchley Park's Greatest Secret. London: Atlantic Books. pp. 495, 17, 18. ISBN 1-84354-330-3.

Sources

[edit]- Beesly, Patrick (1982). Room 40: British Naval Intelligence, 1914–1918. New York: Harcourt, Brace, Jovanovich. ISBN 0-15-178634-8.

- Boghardt, Thomas (November 2003). The Zimmermann Telegram: Diplomacy, Intelligence and The American Entry into World War I (PDF). Working Paper Series. Washington DC: The BMW Center for German and European Studies, Edmund A. Walsh School of Foreign Service, Georgetown University. 6-04. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 2, 2006.; 35pp

- Boghardt, Thomas (2012). The Zimmermann Telegram: Intelligence, Diplomacy, and America's Entry into World War I. Naval Institute Press. p. 319. ISBN 978-1612511481.

- Capozzola, Christopher (2008). Uncle Sam Wants You: World War I and the Making of the Modern American Citizen. Oxford: Oxford Scholarship Online. ISBN 9781803990064.

- Gannon, Paul (July 7, 2022). Before Bletchley Park: The Codebreakers of the First World War. London: Paul Gannon Books. ISBN 9781803990064.

- Hopkirk, Peter (1994). On Secret Service East of Constantinople. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-280230-5.

- Massie, Robert K. (2007). Castles of Steel. London: Vintage Books. ISBN 978-0-09-952378-9.

- Pommerin, Reiner (1996). "Reichstagsrede Zimmermanns (Auszug), 30. März 1917". 'Quellen zu den deutsch-amerikanischen Beziehungen. Darmstadt: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft Vol. 1. pp. 213–16.

- Singh, Simon (September 8, 1999). "The Zimmermann Telegraph". The Independent. Independent Print Limited. Archived from the original on August 14, 2014. Retrieved August 14, 2014. Alt URL

Further reading

[edit]- Bernstorff, Count Johann Heinrich (1920). My Three Years in America. New York: Scribner. pp. 310–11.

- Bridges, Lamar W. (1969). "Zimmermann Telegram: Reaction of Southern, Southwestern Newspapers". Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly. 46 (1): 81–86. doi:10.1177/107769906904600112. S2CID 144936173.

- Dugdale, Blanche (1937). Arthur James Balfour. New York: Putnam. Vol. II, pp. 127–129.

- Hendrick, Burton J. (2003) [1925]. The Life and Letters of Walter H. Page. Kessinger Publishing. ISBN 0-7661-7106-X.

- Kahn, David (1996) [1967]. The Codebreakers. New York: Macmillan.

- Tuchman, Barbara W. The Zimmermann Telegram (1958) online best-seller for the lay reader by the noted historian

- Winkler, Jonathan Reed (2008). Nexus: Strategic Communications and American Security in World War I. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-02839-5.