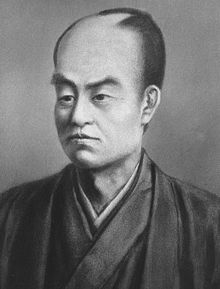

Ōmura Masujirō

This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (January 2017) |

Ōmura Masujirō 大村 益次郎 | |

|---|---|

Ōmura Masujirō | |

| Born | May 30, 1824 |

| Died | December 7, 1869 (aged 45) |

| Nationality | Japanese |

| Occupation(s) | Military theorist and leader |

| Known for | Founding the Imperial Japanese Army |

Ōmura Masujirō (大村 益次郎) (May 30, 1824 – December 7, 1869) was a Japanese military leader and theorist in Bakumatsu period Japan. He was the "Father" of the Imperial Japanese Army, launching a modern military force closely patterned after the French system of the day.

Early life and education

[edit]Ōmura was born in what is now part of Yamaguchi city, in the former Chōshū Domain, where his father was a rural physician. From a young age, Ōmura had a strong interest in learning and medicine, travelling to Osaka to study rangaku under the direction of Ogata Kōan at his Tekijuku academy of western studies when he was twenty-two. He continued his education in Nagasaki under the direction of German physician Philipp Franz von Siebold, the first European to teach Western medicine in Japan. His interest in Western military tactics was sparked in the 1850s and it was this interest that led Ōmura to become a valuable asset after the Meiji Restoration in the creation of Japan's modern army.

Early career

[edit]After studying in Nagasaki, Ōmura returned to his village at the age of twenty-six to practice medicine but accepted an offer from daimyō Date Munenari of nearby Uwajima Domain in 1853 to serve as an expert in Western studies and a military school instructor in exchange for the samurai rank that he was not born into. As foreign incursions into Japanese territorial waters increased, and as pressure from foreign powers for Japan to end its national seclusion policy, Ōmura was sent back to Nagasaki to study the construction of warships and navigation. He traveled to Edo in 1856 in the retinue of Date Munenari and was appointed a teacher at the shogunate's Bansho Shirabesho institute for Western studies. During this time, he also continued his education by learning English under the Yokohama-based American missionary James Curtis Hepburn.[1]

In 1861, Chōshū domain hired Ōmura back to teach at the Chōshū military academy and to reform and modernize the domainal army; they too gave him the ranking of samurai. It was this same year that Ōmura began his involvement with Kido Takayoshi, a political moderate who served as a liaison between the domain bureaucracy and radical elements among the young, lower-echelon Chōshū samurai who supported the Sonnō jōi movement and the violent overthrow of Tokugawa rule.

As a Military Leader

[edit]After his return to Chōshū, Ōmura not only introduced modern western weaponry, but he also introduced the concept of military training for both samurai and commoners. The concept was highly controversial, but Ōmura was vindicated when his troops routed the all-samurai army of the Shogunate in the Second Chōshū Expedition of 1866. These same troops also formed the core of the armies of the Satchō Alliance at the Battle of Toba–Fushimi, Battle of Ueno and other battles of the Boshin War of the Meiji Restoration from 1867 to 1868.

The Making of the Meiji Military

[edit]After the Meiji Restoration, the government recognized the need for a stronger military force that placed their loyalty to the central government as opposed to individual domains. Under the new Meiji government, Ōmura was appointed to the post of hyōbu daiyu, which was equivalent to the role of Vice Minister of War in the newly created Army-Navy Ministry. In this role, Ōmura was tasked with the creation of a national army along Western lines. Ōmura sought to duplicate the policies he had previously successfully implemented in Chōshū on a larger scale, namely, the introduction of conscription and military training for commoners, rather than reliance on a hereditary feudal force. He also strongly supported the discussions towards the abolition of the han system, and with it, the numerous private armies maintained by the daimyō, which he considered a drain on resources and a potential threat to security.

During a council meeting in June 1869, Ōmura argued that if "the government was determined to become militarily independent and powerful, it was necessary to abolish the fiefs and the feudal armies, to do away with the privileges of the samurai class, and to introduce universal military conscription".[2] Ōmura's ideal military consisted of an army patterned after that of the Napoleonic French armies and a navy that was patterned after the British Royal Navy. For this reason, even though the French government had lent tactic support to the Tokugawa regime during the wars of the Meiji Restoration through the supply of weapons and military advisors, Ōmura continued to push for the return of the French military mission to train his new troops.

Ōmura faced opposition from many of his peers, including from most conservative samurai who saw his ideas on modernizing and reforming the Japanese military as too radical. What Ōmura was advocating was not only ending the livelihood of thousands of samurai but also the end of their privileged position in society.

A man of strong character, Ōmura had come to entertain such disgust at the cramped military system of feudalism that a story is told of his refusing to talk to a close companion of arms who offended him by wearing his long samurai sword during a conference.[2]

Assassination

[edit]It was the opposition of some of these samurai that led to his demise in the late 1860s. Although Prince Komatsu Akihito was nominally the minister in charge of military affairs, in practice Ōmura was the guiding force. Ōmura appointed his disciple, Yamada Akiyoshi as a vice minister and placed him in charge with the selection of non-commissioned officer candidates. Yamada selected about 100 people, mainly from various units of Chōshū Domain, and from September 5, began training at the Kawahigashi Training Center established in Kyoto. In September 1869, Ōmura established a military training barracks near Osaka Castle, where French instructors were located. In addition, it was decided that he would build a gunpowder factory in Uji, Kyoto, and an armory (Osaka Artillery Arsenal) in Osaka. His decision to move the core of the army to the Kansai region was partly due to geographic reasons (Osaka was more central than Tokyo, and it would be easier to respond to domestic incidents), and partly due to a desire to remove himself from the Ōkubo faction's obstruction of his military reforms. Despite rumors and concerns raised by Kido Takayoshi and others about threats to Ōmura's life, he decided to make an inspection tour of these new facilities in person. After inspecting the Fushimi Parade Ground in Kyoto, the site of the planned ammunition depot in Uji, military installations in Osaka Castle, and touring the naval base at Tempōzan, he returned to Kyoto on October 8. On the following evening, he had dinner at a ryōkan in Kiyamachi in Kyoto with Shizuma Hikotarō, a commander of a battalion of the Chōshū clan, and Adachi Konosuke, a teacher at the Fushimi Military Academy. In the middle of dinner, he was attacked by eight assassins, including Dan Shinjirō, a former Chōshū retainer. Shizuma and Adachi were killed, and Ōmura was seriously injured, with cuts to his forehead, left temple, arm, right finger, right elbow, and right knee joint, and barely escaped with his life by hiding in a bath full of dirty water. On September 20, he received treatment from Anthonius Franciscus Bauduin, a doctor with the Dutch legation and Ogata Koreyoshi, and was transferred to a hospital in Osaka. His stretcher was carried by Terauchi Masatake and Kodama Gentarō and he was looked after in the hospital by Kusumoto Ine and her daughter Ako. However, his condition did not improve, and he underwent surgery on October 27 to amputate his left thigh by Bauduin. However, as a report to the Ministry of War at the time stated, obtaining permission for the operation from the authorities in Tokyo took too long, and on November 1, he developed a high fever due to sepsis, his condition deteriorated, and he died on the night of the 5th. [3]Ōmura's assassins were soon apprehended and sentenced to death but were reprieved due to political pressure at the last moment by government officials who shared their views that Omura's reforms were an affront to the samurai class. They were executed a year later.

On November 13, Ōmura was posthumously conferred the court rank of Junior Third Rank, and his widow was awarded 300 gold ryō.[a] His body was returned to Yamaguchi where a funeral was held on November 20. His grave is located at the public graveyard in the village of Chusenji, now part of the city of Yamaguchi. The grave was designated as a National Historic Site in 1935.[4] It is located about 25 minutes on foot from Yotsutsuji Station on the JR West San'yō Main Line.[5]

In 1888, his grandson Ōmura Hiroto (the heir of his adopted son) was raised to the kazoku peerage with a title of viscount for his grandfather's achievement. Ōmura core theory of universal military conscription was formally adopted by the Imperial Japanese Army under Yamagata Aritomo in 1873.

Legacy

[edit]

Soon after Ōmura's death, a bronze statue was built in his honor by Ōkuma Ujihiro. The statue was placed in the monumental entry to Yasukuni Shrine, in Tokyo. The shrine was erected to Japanese who have died in battle and remains one of the most visited and respected shrines in Japan. The statue was the first Western-style sculpture in Japan

Ōmura's ideas for modernizing Japan's military were largely implemented after his death by his followers such as Yamagata Aritomo, Kido Takayoshi, and Yamada Akiyoshi.[6] Yamada Akiyoshi was the strongest leader out of the four and was mainly responsible for establishing Japan's modern military using Ōmura's ideas. Yamada promoted Ōmura's ideas by establishing new military academies that taught Ōmura's ways. Yamagata Aritomo and Saigō Tsugumichi also had Ōmura's ideas in mind when passing legislation imposing universal military conscription in 1873.

Yamagata Aritomo, a devoted follower of Ōmura, traveled to Europe to study military science and military techniques that could be adapted in Japan. Upon returning from Europe, he organized a 10,000-man force to form the core of the new Imperial Japanese Army. As Ōmura had hoped for, the French military mission returned in 1872 to help equip and train the new army. Although Ōmura died before having the opportunity to enforce many of his radical ideas, the lasting impression that he left on his followers led to his policies and ideas shaping the making of the Meiji military years later.

Notes

[edit]- ^ About 3.3 grams of gold each ryo or US$123 according to bullion price of gold. Then 300 ryos would be about US$36,900. It is unclear how the inflation has affected Japan compared to that period. But in the US, the purchasing power was around 20 times greater in those times than in the 2020s.

- ^ Keane. Emperor Of Japan: Meiji And His World, 1852–1912. page 195

- ^ a b Kublin, The "Modern" Army of Early Meiji Japan

- ^ Drea. Japan's Imperial Army: Its Rise and Fall:1853-1945. page 21

- ^ "大村益次郎墓" (in Japanese). Agency for Cultural Affairs. Retrieved August 20, 2021.

- ^ Isomura, Yukio; Sakai, Hideya (2012). (国指定史跡事典) National Historic Site Encyclopedia. 学生社. ISBN 978-4311750403.(in Japanese)

- ^ Norman. Soldier and Peasant in Japan.

References and further reading

[edit]- Huber, Thomas. The Revolutionary Origins of Modern Japan. Stanford University Press (1981)

- Kublin, Hyman. "The 'Modern' Army of Early Meiji Japan". The Far Eastern Quarterly, Vol. 9, No. 1. (November, 1949), pp. 20–41.

- Norman, E. Herbert. "Soldier and Peasant in Japan: The Origins of Conscription." Pacific Affairs 16#1 (1943), pp. 47–64.

- Steele, M. William (Autumn 1981). "Against the Restoration. Katsu Kaishu's Attempt to Reinstate the Tokugawa Family". Monumenta Nipponica. 36 (3): 299–316. doi:10.2307/2384439. JSTOR 2384439.

- Keane, Donald (2005). Emperor Of Japan: Meiji And His World, 1852–1912. Columbia University Press. ISBN 0-231-12341-8.

External links

[edit]- 1824 births

- 1869 deaths

- People from Yamaguchi (city)

- Japanese military leaders

- Meiji Restoration

- People of Meiji-period Japan

- Assassinated Japanese politicians

- People murdered in Japan

- 1869 murders in Japan

- People assassinated in the 19th century

- Politicians assassinated in the 1860s

- Deaths by stabbing in Japan