Dark Passage (film)

| Dark Passage | |

|---|---|

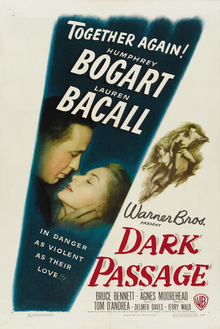

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Delmer Daves |

| Screenplay by | Delmer Daves |

| Based on | Dark Passage 1946 novel by David Goodis |

| Produced by | Jerry Wald |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Sidney Hickox |

| Edited by | David Weisbart |

| Music by | Franz Waxman |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | Warner Bros. |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 106 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $1.6 million[1] |

| Box office | $3.4 million[1][2] |

Dark Passage is a 1947 American film noir directed by Delmer Daves and starring Humphrey Bogart and Lauren Bacall.[3][4] The film is based on the 1946 novel of the same title by David Goodis. It was the third of four films real-life couple Bacall and Bogart made together.[5]

The story follows protagonist Vincent Parry’s attempt to hide from the law and clear his name of murder.[4] The first portion of the film subjectively depicts the male lead's point of view, concealing Bogart‘s face until his character undergoes plastic surgery to change his appearance.

Plot

[edit]

Convicted wife-killer Vincent Parry escapes from San Quentin Prison and evades police by hitching a ride with a passing motorist. Already suspicious of Parry's appearance, its driver hears a radio news report about an escaped convict; Parry resorts to beating him unconscious. Wealthy dilettante Irene Jansen, a passing stranger, picks Parry up and smuggles him past a police roadblock into San Francisco. She offers him shelter in her apartment while she goes to buy him some new clothes.

Irene's acquaintance Madge comes by Irene's apartment, but Parry turns her away. A former romantic interest whom Parry had spurned, Madge testified at his trial out of spite, claiming that his dying wife identified him as the killer. Later Irene explains that she had followed Parry's case with interest and that she believes Parry is innocent. Her own father had been falsely convicted of murder, and since then she has taken an interest in such miscarriages of justice.

Parry leaves but is recognized by his cab driver, Sam, who proves sympathetic and gives him the name of a plastic surgeon who can change his appearance. Parry arranges to stay with a friend, George, during his recuperation from surgery. When Parry returns to George's apartment he finds him murdered. Parry retreats to Irene's apartment, who nurses him through his recuperation. He learns that his fingerprints were found on George's trumpet and he is wanted for murder.

Irene is called upon by Madge and Madge’s ex-fiancé Bob, who is romantically interested in Irene. Madge is worried that Parry will kill her for testifying against him, and asks to stay with Irene for protection. While Parry overhears from the bedroom, Irene insists that Madge leave. Before she does, Madge intentionally reveals in front of Bob that Irene recently had a male guest. More disgusted with Madge’s behavior than learning of a new romantic rival, Bob drags her hastily off.

After his bandages are removed, Parry reluctantly parts from Irene. Recognizing his peril, he decides to flee the city before trying to prove his innocence. At a diner, an undercover policeman becomes suspicious of his behavior. The detective asks for identification, but Parry claims to have left it at his hotel. Parry darts in front of a moving car to escape. Finding a hotel to hide in, he is surprised by the man he’d knocked out the day of his escape. Baker, a callow schemer and fellow ex-con of San Quentin, has been following Parry ever since. Holding Parry at gunpoint, he now demands that Irene pay him $60,000, a third of what she’s worth, or he will turn Parry in for a $5,000 reward. Parry agrees, and Baker obliges him to drive the pair to Irene's apartment. Claiming to take a shortcut, Parry detours to a secluded spot underneath the Golden Gate Bridge, disarms Baker, and questions him; the answers convince Parry that Madge is behind the deaths of his wife and George. The two men fight, and Baker falls to his death.

Parry goes to Madge's apartment. Knowing she does not recognize him with his new face, he pretends to be a friend of Bob's and feigns interest in courting her. He soon reveals his true identity and accuses Madge of the two murders. He shows her that he has all the accusations written down, and attempts to coerce her into a confession. She refuses, and during their argument dashes behind a curtain and plunges through a window to her death.

Knowing he cannot prove his innocence, and that he will likely be accused of Madge's murder as well, Parry decides again to flee. In a bus station, he sees a man and woman talking agitatedly; he puts a romantic song on a jukebox, and the man and woman calm down. He phones Irene, telling her to meet him in seaside Paita, Peru; she promises she will.

As Parry has a drink in a palm-studded bar, Irene appears. The couple passionately embraces, as the song he played in the bus station plays again.

Cast

[edit]

- Humphrey Bogart as Vincent Parry

- Lauren Bacall as Irene Jansen

- Agnes Moorehead as Madge Rapf

- Bruce Bennett as Bob

- Tom D'Andrea as Cabby (Sam)

- Clifton Young as Baker

- Douglas Kennedy as Detective Kennedy in Diner

- Rory Mallinson as George Fellsinger

- Houseley Stevenson as Dr. Walter Coley

- Mary Field as Aunt Mary at Bus Station (uncredited)

- John Arledge as Lonely Man at Bus Station (uncredited)

- Frank Wilcox as Vincent Parry (picture in the newspaper, uncredited)

Production

[edit]Warner Bros. paid author David Goodis $25,000 for the rights to the story, which had originally been serialized in The Saturday Evening Post from July 20 to September 7, 1946, before being published in book form.[6] Bogart himself had read the book and wanted to make it into a movie.[7] At the time that Dark Passage was shot, Bogart was the best-paid actor in Hollywood, averaging $450,000 a year.[8]

Robert Montgomery had made the film Lady in the Lake (1946) which also uses a "subjective camera" technique, in which the viewer sees the action through the protagonist's eyes. This technique was used in 1927 in France by Abel Gance for Napoléon[9] and by the director Rouben Mamoulian for the first five minutes of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (1931). Film critic Hal Erikson believes Dark Passage does a better job at using this point-of-view technique, writing, "The first hour or so of Dark Passage does the same thing—and the results are far more successful than anything seen in Montgomery's film."[10]

According to Bacall, in her autobiography By Myself, during the filming of Dark Passage, Bogart's hair began to fall out in clumps, the result of alopecia areata, although photos from their 1945 wedding show Bogart to be losing his hair two years earlier. By the end of filming he wore a full wig. Bogart eventually had B12 shots and other treatments to counteract the effects, but was forced to wear a full wig in his next picture, The Treasure of the Sierra Madre.[8]

Filming locations

[edit]Parts of the film were filmed on location in San Francisco, California, including the Filbert Steps and the cable car system. The elegant Streamline Moderne Malloch Building on Telegraph Hill was used for the apartment of Irene Jansen where Parry hides out and recuperates from his surgery.[11][12][13] Apartment Number 10 was Jansen's. The current residents of that apartment occasionally place a cutout of Bogart in the window.[14] The tiny diner was "Harry's Wagon" at 1921 Post Street, a long-closed beanery in the Fillmore District of San Francisco.[citation needed]

Reception

[edit]Box office

[edit]The film earned $2.31 million domestically and $1.11 million in overseas markets, for a worldwide total of $3.4 million.[1]

Critical response

[edit]The New York Times film critic Bosley Crowther gave the film a mixed review and was not impressed by Bogart's performance but was impressed by Bacall's work. He wrote:[citation needed]

When [Bogart] finally does come before the camera, he seems uncommonly chastened and reserved, a state in which Mr. Bogart does not appear at his theatrical best. However, the mood of his performance is compensated somewhat by that of Miss Bacall, who generates quite a lot of pressure as a sharp-eyed, knows-what-she-wants girl.

He made the case that the best part of the film is:[15]

San Francisco ... is liberally and vividly employed as the realistic setting for the Warners' Dark Passage. Writer-Director Delmar Daves has very smartly and effectively used the picturesque streets of that city and its stunning panoramas ... to give a dramatic backdrop to his rather incredible yarn. So, even though bored by the story—which, because of its sag, you may be—you can usually enjoy the scenery, which is as good as a travelogue.

The Chicago Tribune laid out the plot’s many implausibilities:

“If you have the right friends, it really is a simple matter to break out of San Quentin, obtain shelter and a thousand dollars, have your face remodeled so completely that even your closest acquaintance won’t recognize you, escape from a smart detective, avoid implication despite being on the scene where three different people die, and retire to live happily ever after in a picturesque Peruvian town with a gal who loves you and has $200,000. If you don’t believe it, just watch Humphrey Bogart in his latest, although I can’t think of any other reason for seeing it....on the whole, 'Dark Passage’ is completely preposterous.”.[16]

The Philadelphia Inquirer wrote:

“Borrowing heavily from ‘Lady in the Lake’ for tricky technique…Daves has provided new and fancy trimming for the not unfamiliar yarn of the escaped convict bent on establishing his innocence….on [Bogart’s] side, and for no convincing reason, is Lauren Bacall, lovely, wealthy landscape painter who picks him up in her station wagon during the early moments of his escape and whisks him home to her luxurious duplex. Also generously helping the wrongly accused wife-killer are a philosophic taxi driver and a wonderful plastic surgeon….Although the plot doesn’t bear too much close inspection, performances and direction lend considerable fascination to a desperate man’s struggle for freedom….Miss Bacall is attractive and very, very efficient…while Agnes Moorehead is about as mean as they come….Supporting roles are exceptionally well played.”[17]

On Rotten Tomatoes the film held an approval rating of 90% based on 31 reviews as of 2022, with an average rating of 7.7/10.[18] Metacritic assigned the film a weighted average score of 68 out of 100, based on 10 critics, indicating "generally favorable reviews".[19]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c Warner Bros financial information in The William Schaefer Ledger. See Appendix 1, Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television, (1995) 15:sup1, 1–31 p 28 DOI: 10.1080/01439689508604551

- ^ "Top Grossers of 1947". Variety. January 7, 1948, p. 63.

- ^ Variety film review; September 3, 1947, p. 16.

- ^ a b Harrison's Reports film review; September 6, 1947, p. 142.

- ^ The first two Bacall-Bogart films were To Have and Have Not (1944) and The Big Sleep (1946); the fourth would be Key Largo (1948). Dark Passage at IMDb.

- ^ "Notes" on TCM.com

- ^ Hold Your Breath and Cross Your Fingers: The Story of 'Dark Passage' (2003). Warner Bros. Entertainment.

- ^ a b Stafford, Jeff. "Dark Passage" on TCM.com

- ^ Brownlow, Kevin (1983). Napoleon: Abel Gance's Classic Film (1st ed.). New York: Knopf. pp. 56–57. ISBN 0-394-53394-1.

- ^ Erikson, Hal. Dark Passage at AllMovie.

- ^ CitySleuth (November 7, 2010). "Dark Passage – Irene's Apartment". ReelSF.com. Retrieved July 22, 2013.

- ^ Poletti, Therese (January 20, 2012). "Streamline Moderne gem a quiet star in "Dark Passage" at Noir City Film Festival". Retrieved July 22, 2013.

- ^ King, John (June 14, 2009). "Malloch building: suave delight on storied hill". SFGate. Retrieved July 22, 2013.

- ^ Boxer, Lou (October 29, 2010). "NoirCon and David Goodis revisit Dark Passage in San Francisco". NoirCon. Retrieved February 21, 2012.

- ^ Bosley Crowther (September 6, 1947). "'Dark Passage,' Warner Thriller, in Which Humphrey Bogart and lauren Bacall Are Chief Attractions, Opens at Strand". The New York Times. p. 11. Retrieved December 21, 2007.

- ^ Tinee, Mae. “Newest Bogart and Bacall Film is Far Fetched: ‘Dark Passage’.” Chicago Tribune, 31 October 1947, 28

- ^ Martin, Mildred. “’Dark Passage’ on Earle Screen With the Humphrey Bogarts.” Philadelphia Inquirer, 18 September 1947, 22.

- ^ Dark Passage at Rotten Tomatoes. Last accessed: August 18, 2022.

- ^ Dark Passage at Metacritic. Last accessed: August 18, 2022.

External links

[edit]- Dark Passage at IMDb

- Dark Passage at the TCM Movie Database

- Dark Passage at AllMovie

- Dark Passage at the AFI Catalog of Feature Films

- Dark Passage trailer at Spike TV

- 1947 films

- 1947 crime films

- 1940s crime thriller films

- 1940s mystery thriller films

- American black-and-white films

- American crime thriller films

- American mystery thriller films

- 1940s English-language films

- English-language crime thriller films

- Film noir

- Films about miscarriage of justice

- Films based on American crime novels

- Films based on mystery novels

- Films directed by Delmer Daves

- Films scored by Franz Waxman

- Films set in San Francisco

- Films set in San Quentin State Prison

- Films shot from the first-person perspective

- Films shot in San Francisco

- Murder mystery films

- Warner Bros. films

- Films about plastic surgery

- 1940s American films

- English-language mystery thriller films