Marek Edelman

Marek Edelman | |

|---|---|

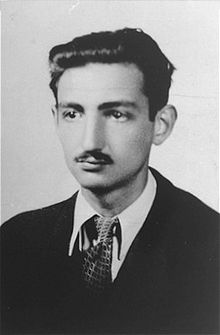

Marek Edelman at around the time of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising | |

| Born | 1919 or 1922 Homel, Ukrainian People's Republic, or Warsaw, Poland |

| Died | October 2, 2009 (aged 90 or 87) Warsaw, Poland |

| Buried | |

| Allegiance | |

| Years of service | 1942–1944 |

| Rank | Deputy commander (ŻOB) |

| Battles / wars | |

| Awards | French Legion of Honor[1][2] Order of the White Eagle[1] Yale University, honorary doctorate[1] |

Marek Edelman (Yiddish: מאַרעק עדעלמאַן; 1919/1922 – October 2, 2009) was a Polish political and social activist and cardiologist. Edelman was the last surviving leader of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising. Long before his death, he was the last one to stay in the Polish People's Republic despite harassment by the Communist authorities.[3]

Before World War II, he was a General Jewish Labour Bund activist. During the war he co-founded the Jewish Combat Organization (ŻOB). He took part in the 1943 Warsaw Ghetto Uprising, becoming its leader after the death of Mordechaj Anielewicz. He also took part in the citywide 1944 Warsaw Uprising.[4]

After the war, Edelman remained in Poland and became a noted cardiologist. From the 1970s, he collaborated with the Workers' Defence Committee and other political groups opposing Poland's Communist regime. As a member of Solidarity, he took part in the Polish Round Table Talks of 1989. Following the peaceful transformations of 1989, he was a member of various centrist and liberal parties.[5] He also wrote books documenting the history of wartime resistance against the Nazi German occupation of Poland.[6]

Early life

[edit]Details of Marek Edelman's birth are not known for certain; sources give two possible years of birth, either 1919 in Homel (present-day Belarus),[7][8] or in 1922 in Warsaw.[1] His father, Natan Feliks Edelman (died 1924), was a member of the Socialist Revolutionary Party (his father's brothers, also Socialist Revolutionaries, were executed by the Bolsheviks).[7] His mother, Cecylia Edelman (died 1934), a hospital secretary, was an activist member of the General Jewish Labour Bund, a Jewish socialist workers' party.[7] When Edelman's mother Cecylia died, he was 14 years old, and was looked after by other staff members at the hospital where she had worked in Warsaw, the city he always called home.[9] He said in 2001: "Warsaw is my city. It is here that I learned Polish, Yiddish and German. It is here that at school, I learned one must always take care of others. It is also here that I was slapped in the face just because I was a Jew."[9]

As a child, Edelman was a member of Sotsyalistishe Kinder Farband (SKIF), the Jewish Labour Bund's youth group for children.[10]

In 1939 he joined and became a leader in Tsukunft (Future), the Bund's youth organization for older children.[11] During the war, he restarted these organizations inside the Warsaw Ghetto.[12]

The defiance and organization of the Bund made their mark on Edelman. As conditions for Jews worsened in the 1930s, Bund members preferred to challenge the mounting antisemitism rather than flee. Edelman later said: "The Bundists did not wait for the Messiah, nor did they plan to leave for Palestine. They believed that Poland was their country, and they fought for a just, socialist Poland in which each nationality would have its own cultural autonomy, and in which minorities' rights would be guaranteed."[9]

World War II

[edit]

"The most important is life, and when there is life, the most important is freedom. And then we give our life for freedom..."

Mural of Edelman on a Mila Street school just west of the Anielewicz Bunker memorial. "Hate is easy, love requires effort and sacrifice."

In 1939, after the German invasion of Poland Edelman found himself confined—along with the other Jews of Warsaw—to the Warsaw Ghetto. In 1942, as a Bund youth leader he co-founded the underground Jewish Combat Organization (Żydowska Organizacja Bojowa, ŻOB). In the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising of April–May 1943, led by Mordechaj Anielewicz, Edelman was one of the three sub-commanders and then became the leader after the death of Anielewicz.[13]

When the Germans had stopped their campaign of transporting Ghetto residents to Treblinka extermination camp in September 1942, only 60,000 had remained.[9] Edelman and his comrades, however, had had little doubt that the Germans would resume the job. The Jewish Combat Organisation had begun acquiring weapons and organizing into units that would make up for lack of training and munitions with an intimate knowledge of the ghetto, both above ground and in its sewer network.[9]

The Germans resumed their attack on the ghetto on April 19, 1943, with over 2,000 troops. According to Edelman: "The Germans weren't expecting resistance of any kind, let alone that we would take up arms." The outnumbered and outgunned Ghetto fighters' strong resistance forced the German troops to withdraw.[9] It was on the second day of the Uprising, while protecting the retreat of Edelman and other comrades, that another prominent insurgent and Bundist, Michał Klepfisz, was killed.[14] Over the next three weeks, the fighting was intense. The Jewish fighters killed and wounded scores of Nazis but inevitably sustained far greater losses. On May 8, ŻOB's commander, Mordechaj Anielewicz, was surrounded by German forces. Anielewicz died during the final assault on the ŻOB's bunker on 8 May 1943, which meant that now Edelman was in charge. "After three weeks," he recalled, "most of us were dead."[9]

The Germans proceeded to flush out the few remaining fighters by burning down the ghetto - Edelman always insisted, "We were beaten by the flames, not the Germans."[9] At that juncture, couriers from the Polish underground outside the ghetto came through the sewers that still linked it with the rest of Warsaw.[15] On the morning of May 10, Edelman and his few remaining comrades escaped through the sewers and made their way to the non-Ghetto part of Warsaw to find safety among their Polish compatriots. At this point the Uprising was over and the fate of those fighters who had remained behind is unknown.[9]

After World War II, the Ghetto Uprising was sometimes given as an unusual instance of active Jewish resistance in the face of the horror perpetrated by the Germans. However, Marek never saw a difference in the character of those who fought in the Uprising and those who were sent to the death camps, as, in his view, all involved were simply dealing with an inevitable death as well as they knew how.[9]

"We knew perfectly well that we had no chance of winning. We fought simply not to allow the Germans alone to pick the time and place of our deaths. We knew we were going to die. Just like all the others who were sent to Treblinka.... Their death was far more heroic. We didn't know when we would take a bullet. They had to deal with certain death, stripped naked in a gas chamber or standing at the edge of a mass grave waiting for a bullet in the back of the head.... It was easier to die fighting than in a gas chamber."[9]

In mid-1944, Edelman, as a member of the leftist Armia Ludowa (People's Army), participated in the citywide Warsaw Uprising, when Polish forces rose up against the Germans before being forced to surrender after 63 days of fighting.[16] After the capitulation, Edelman together with a group of other ŻOB fighters, hid out in the ruins of the city as one of the Robinson Crusoes of Warsaw before being rescued and evacuated with the help from the centrist Armia Krajowa (Home Army).[17]

Later life

[edit]

Edelman's hospital upbringing had proven invaluable in the Warsaw Ghetto. After World War II, he studied at Łódź Medical School and became a noted cardiologist who invented an original life-saving operation.[18] In 1948, Edelman actively opposed the incorporation of the Bund into the Polish United Workers' Party (Poland's Communist party), which led to the Communists disbanding the organization.[19] In 1976, he became an activist with the Workers' Defence Committee (Komitet Obrony Robotników)[20] and later with the Solidarity movement.[16] Edelman publicly denounced racism and promoted human rights.[13]

In 1981, when General Wojciech Jaruzelski declared martial law, Edelman was interned by the government.[16] In 1983, he refused to take part in the official celebrations of the 40th anniversary of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising sponsored by Poland's Communist government,.[21]

In an open letter dated February 2, 1983, he wrote of his refusal of invitation:

Forty years ago we fought not only for our lives. We fought for life in dignity and freedom. To celebrate our anniversary there where social life is dominated throughout by humiliation and coercion would be to deny our fight.

Hanna Krall, "Shielding the Flame"

A couple of days before the official event, on April 17, 1983, several hundred Solidarity members staged a commemoration of their own, gathering spontaneously at the Warsaw Ghetto Memorial. Edelman was then prevented from being present at this occasion because he was being held under house arrest back in Lodz. Edelman sat in his house surrounded by the police cars, at a table set for a fancy dinner which included empty places because the police were not letting the guests in, except the journalist Hanna Krall.[22]

In post-Communist Poland, Edelman was a member of several centrist liberal parties: the Citizens' Movement for Democratic Action, Democratic Union, Freedom Union and Democratic Party – demokraci.pl. He supported the 1999 NATO bombing of Yugoslavia as well as the 2003 Iraq war, both of which he saw as instances of American democracy saving countries from fascism again.[23][24][25]

Edelman lent public support to anti-fascist initiatives and to organisations combatting antisemitism. In 1993, he accompanied a convoy of goods into the city of Sarajevo while that city was under siege.[26] Edelman strongly condemned international indifference during the Bosnian Genocide in the early 1990s, calling it a disgrace for the rest of Europe and "a delayed victory by Hitler – a victory from the grave."[27][28]

On April 17, 1998,[29] Edelman was awarded Poland's highest decoration, the Order of the White Eagle.[1] He received the French Legion of Honour.[2]

Edelman was a lifelong anti-Zionist.[30][31][32] In a 1985 interview, he said Zionism was a "lost cause" and questioned Israel's viability.[33] He remained firmly Polish, refusing to emigrate to Israel.[34] In his old age, Edelman spoke in defence of the Palestinian people, as he felt that the Jewish self-defence for which he had fought was in danger of crossing the line into oppression.[35] In August 2002, he wrote an open letter to the Palestinian resistance leaders. Although the letter criticised the Palestinian suicide attacks, its tone infuriated the Israeli government and press. According to the late British writer and activist Paul Foot, "He wrote [the letter] in a spirit of solidarity from a fellow resistance fighter, as a former leader of a Jewish uprising not dissimilar in desperation to the Palestinian uprising in the occupied territories."[36] He addressed his letter "To all the leaders of Palestinian military, paramilitary and guerrilla organizations – To all the soldiers of Palestinian militant groups."[37]

Family life

[edit]Marek Edelman was married to Alina Margolis-Edelman (1922–2008). They had two children, Aleksander and Anna.[2][34] When his wife and children emigrated from Poland to France in the wake of the 1968 Polish political crisis and antisemitic actions by the Polish Communist authorities, Edelman decided to stay in Łódź. "Someone had to stay here with all those who perished here, after all."[9] He published his memoirs, which have been translated into six languages.[34] Each April he laid flowers in Warsaw for those he had served with in the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising.[2] Edelman's wife Alina, likewise a Warsaw Ghetto survivor, died in 2008. They were survived by their son and daughter.[9]

Death

[edit]

Edelman died on October 2, 2009.[2][13][38] He was buried in Warsaw with full military honours on October 9, 2009. His coffin was covered with a Bund banner inscribed "Bund - Yidisher Sozialistisher Farband," and a choir sang the Bund anthem, "Di Shvue."[39] The Polish President Lech Kaczyński and the former President Lech Wałęsa were present at the funeral, attended by about 2,000 persons.[40]

Władysław Bartoszewski, former Polish Minister of Foreign Affairs and an Auschwitz survivor, led the tributes to Edelman, saying: "He reached a good age. He left as a contented man, even if he was always aware of the tragedy he went through."[13][38] Bartoszewski denied that the activist was "irreplaceable," before acknowledging that "there are few people like Marek Edelman."[13][38] Roman Catholic Bishop Tadeusz Pieronek said: "I respect him most for the fact that he stayed in this land, which made him fight so hard for his Jewish and Polish identity. He became a real witness, he gave a real testimony with his life."[41] The former Polish Prime Minister, Tadeusz Mazowiecki, was also present and said Edelman had been a role model for him.[40]

Former head of Israel's parliament and former Israeli ambassador to Poland Shevah Weiss said: "I'd like to offer my condolences to Marek Edelman's family, to the Polish nation and to the Jewish nation. He was a hero to all of us."[38] Ian Kelly, official spokesperson for the United States, expressed sympathies and affirmed that the United States "stands with Poland as it mourns the loss of a great man."[42]

In popular culture

[edit]In the 2001 television film Uprising, he was portrayed by American actor John Ales.

The documentary Marek Edelman... And There Was Love in the Ghetto, directed by Andrzej Wajda and Jolanta Dylewska, was released in 2019.

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ a b c d e Scislowska, Monika, "Warsaw ghetto uprising leader Edelman dies at 90", News, Associated Press, retrieved 1 November 2015

- ^ a b c d e "Warsaw Ghetto uprising leader Marek Edelman dies at 90". The Daily Telegraph. London, UK. 3 October 2009. Retrieved 4 October 2009.

- ^ Lucy S. Dawidowicz, "The Curious Case of Marek Edelman", Commentary Magazine, March 1, 1987

- ^ Richie, Alexandra (10 December 2013). Warsaw 1944: Hitler, Himmler, and the Warsaw Uprising. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. ISBN 9781466848474.

- ^ Zychowicz, Piotr (2 October 2009). "Marek Edelman nie zyje". Rzeczpospolita (in Polish). Retrieved 3 November 2009.

- ^ Edelman, Marek (4 February 2014). The Ghetto Fights. Bookmarks. ISBN 9781909026391. See the External Links, below, for the full text.

- ^ a b c "Marek Edelman - biografia"; accessed November 1, 2015.

- ^ Jerzy B. Warman, In Memoriam Archived 2011-07-07 at the Wayback Machine, American Gathering of Jewish Holocaust Survivors and their Descendants; accessed November 1, 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Marek Edelman - Daily Telegraph obituary.

- ^ Izabela Leszczyńska, Maciej Stańczyk, "Zmarł Marek Edelman" Archived 2009-10-04 at the Wayback Machine, kurierlubelski.pl, March 10, 2009. (in Polish)

- ^ Mendelsohn, Ezra (31 March 2009). Jews and the Sporting Life: Studies in Contemporary Jewry XXIII. Institute of Contemporary Jewry, Hebrew University of Jerusalem. p. 27. ISBN 978-0-19-538291-4.

- ^ Yitzhak Zuckerman, Barbara Harshav, "A surplus of memory: chronicle of the Warsaw Ghetto uprising", University of California Press, 1993, pg. 434.

- ^ a b c d e "Warsaw ghetto uprising head dies". BBC. 2 October 2009. Retrieved 4 October 2009.

- ^ Israel Gutman, Resistance: The Warsaw Ghetto Uprising, New York, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 1998, p. 214.

- ^ "Marek Edelman - charakterystyka - Hanna Krall". poezja.org. Retrieved 2 June 2022.

- ^ a b c Kaufman, Michael T. (3 October 2009). "Marek Edelman, Commander in Warsaw Ghetto Uprising, Dies at 90". The New York Times. p. A21. Retrieved 5 October 2009.

- ^ Engelking, Barbara; Libionka, Dariusz (2009). Żydzi w Powstańczej Warszawie. Warsaw: Stowarzyszenie Centrum Badań nad Zagładą Żydów. pp. 260–293. ISBN 978-83-926831-1-7.

- ^ Lichterman, Boleslav (28 November 2009). "Marek Edelman". British Medical Journal. 339: 1257. doi:10.1136/bmj.b4992. S2CID 220116107.

- ^ ""Marek Edelman 1919-2009", Żydowski Instytut Historyczny". Archived from the original on 23 June 2012. Retrieved 13 October 2009.

- ^ "Rz" Online, "Pożegnanie Marka Edelmana" (Farewell to Marek Edelman), Rzeczpospolita; accessed November 1, 2015, rp.pl Archived 2015-06-26 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Marek Edelman nie żyje" (in Polish). Dziennik. 2 October 2009. Archived from the original on 4 October 2009. Retrieved 5 October 2009.

- ^ Krall, Hanna (1986). Shielding the Flame — An Intimate Conversation with Dr. Marek Edelman, the Last Surviving Leader of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising. New York: Henry Holt & Company. ISBN 0-03-006002-8.

- ^ Andrzej STYLINSKI, "Marek Edelman; Wartime Jewish hero of Warsaw ghetto uprising", eilatgordinlevitan.com; accessed November 1, 2015.

- ^ "Every war with fascism is our business". Interview by Polish Channel TVN24, re-published in a Polish weekly Przekroj (translated by Arthur Chrenkoff), May 30, 2004; accessed November 1, 2015.

- ^ Letter to the Editor, nytimes.com; accessed November 1, 2015.

- ^ Mendelsohn, Ezra (31 March 2009). Jews and the Sporting Life: Studies in Contemporary Jewry XXIII. Institute of Contemporary Jewry, Hebrew University of Jerusalem. p. 34. ISBN 978-0-19-538291-4.

- ^ "A delayed victory by Hitler...", independent.co.uk, August 18, 1993.

- ^ Tilman Zülch, "A disgrace for Europe!' Archived 2014-04-25 at the Wayback Machine, gfbv.de, March 2, 2011.

- ^ Official website of the President of Poland, Archives Archived 1 December 2020 at the Wayback Machine, accessed November 1, 2015,

- ^ Boyarin, Jonathan; Boyarin, Daniel (2002). Powers of Diaspora: Two Essays on the Relevance of Jewish Culture. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press. p. 53. ISBN 0-8166-3596-X.

- ^ Kaye/Kantrowitz, Melanie (2007). The Colors of Jews: Racial Politics and Radical Diasporism. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press. p. 214. ISBN 978-0-253-34902-6.

- ^ Zertal, Idith (2005). Israel's Holocaust and the Politics Of Nationhood. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 34–35. ISBN 0-521-85096-7.

- ^ Grupinska, Anna (1985). "Talk with Marek Edelman". CZAS.

- ^ a b c Yossi Melman (2 October 2009). "Hero of Warsaw Ghetto uprising, Marek Edelman, dies at 86". Haaretz. Retrieved 25 December 2023.

- ^ "Marek Edelman: death of a great man". The Daily Telegraph. London, UK. 5 October 2009. Archived from the original on 8 October 2009.

- ^ Paul Foot (21 August 2002). "Palestine's partisans". The Guardian. London, UK.

- ^ "Anti-Zionist Legacy of Warsaw Ghetto Resistance Fighter Marek Edelman". Daily Kos. 15 October 2009. Retrieved 19 April 2013.

- ^ a b c d "Marek Edelman of Warsaw Ghetto Uprising dies". The Australian. 3 October 2009. Retrieved 4 October 2009.

- ^ Moshe Arens, "Requiem for the Bund", Haaretz, [1]

- ^ a b "פֿון "אַרבעטער־רינג" אין ישׂראל די בונדישע "שבועה", די פֿאָן און אַ קראַנץ (Di Shvue, the banner and a wreath of the Arbeter-ring in Yisroel)" (in Yiddish). Lebns Fragn (bimonthly of the Bund Israeli branch). September–October 2009. Retrieved 3 November 2009.

- ^ Gabriela Baczynska (3 October 2009). "Last leader of Warsaw Jewish Ghetto Uprising dies at 87". Reuters India. Archived from the original on 10 January 2016. Retrieved 4 October 2009.

- ^ "Poland: Death of Marek Edelman". United States Department of State. 3 October 2009. Retrieved 4 October 2009.

Further reading

[edit]- Witold Bereś, Krzysztof Burnetko, Marek Edelman. Życie. Po prostu,Świat Książki 2008, ISBN 978-83-247-0892-5

- Marek Edelman, Resisting the Holocaust: Fighting Back in the Warsaw Ghetto, Ocean Press, 2004; ISBN 1-876175-52-4, (Excerpt online)

- Marek Edelman, I była miłość w getcie (spisała Paula Sawicka; Świat Książki 2009, ISBN 978-83-247-1416-2)

- Krall, Hanna (1986). Shielding the flame : an intimate conversation with Dr. Marek Edelman, the last surviving leader of the Warsaw Ghetto uprising. New York: Henry Holt and Co. ISBN 0030060028. OCLC 970836088. OL 2707703M. Retrieved 15 February 2022. Reprinted as To Outwit God, in Krall, Hanna (1992). The subtenant; To outwit God. Evanston, Ill: Northwestern University Press. ISBN 0810110504. OCLC 1285856049. Retrieved 18 December 2022.

- Krzysztof Lesiakowski, Marek Edelman, [In:]: Opozycja w PRL. Słownik biograficzny 1956-89, Vol. 1, Ośrodek Karta, Warsaw 2000 ISBN 83-88288-65-2.

- Katarzyna Zechenter, Marek Edelman, [In:] Holocaust Literature. An Encyclopedia of Writers and Their Work. Vol. 1, Routledge 2003, pp. 288–90; ISBN 0-415-92983-0 https://www.academia.edu/4983698/Marek_Edelman_and_His_Account_Ghetto_Fights

External links

[edit]- The Ghetto Fights by Marek Edelman

- Edelman Biography

- Marek Edelman's Life Story on Web of Stories (video interview in Polish with English subtitles)

- A True Mensch - Obituary to Marek Edelman

- John Rose. “Marek Edelman — star of resistance among Nazi horror” Archived 26 March 2010 at the Wayback Machine Socialist Worker (UK), January, 2006

- Last Warsaw ghetto revolt commander honours fallen comrades

- A Life of Resistance: Marek Edelman, 90, Last Ghetto Uprising Commander, Michael Berenbaum and Jon Avnet, The Forward, October 7, 2009

- Yiddish: Isaac Laden, געשטאָרבן דער לעצטער קאָמאַנדיר פֿון װאַרשעװער געטאָ - מאַרעק עדעלמאַן (Marek Edelman, 1919-2009. Death of the last commandant of the Warsaw ghetto), Lebns Fragen, September–October 2009

- Marci Shore, "The Jewish Hero History Forgot", New York Times, April 19, 2013.

- 2009 deaths

- 20th-century Polish Jews

- 21st-century Polish Jews

- 21st-century Polish physicians

- Commanders of the Legion of Honour

- Democratic Party – demokraci.pl politicians

- General Jewish Labour Bund in Poland politicians

- Bundism in Europe

- Bundists

- Anti-Zionist Jews

- Jewish anti-communists

- Jewish anti-fascists

- Jewish socialists

- Jewish Combat Organization members

- Jewish resistance members during the Holocaust

- Writers about the Holocaust

- Members of the Polish Sejm 1991–1993

- Members of the Workers' Defence Committee

- People from Gomel

- Polish anti-communists

- Polish cardiologists

- Polish dissidents

- Polish atheists

- Polish socialists

- Polish Round Table Talks participants

- Solidarity (Polish trade union) activists

- Warsaw Ghetto inmates

- Warsaw Uprising insurgents

- Politicians of Jewish political parties

- Recipients of the Order of the White Eagle (Poland)