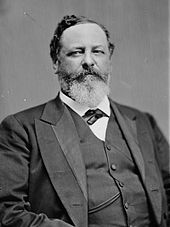

George H. Pendleton

George H. Pendleton | |

|---|---|

| |

| United States Minister to Germany | |

| In office June 21, 1885 – April 25, 1889 | |

| President | Grover Cleveland Benjamin Harrison |

| Preceded by | John A. Kasson |

| Succeeded by | William Phelps |

| Chairman of the Senate Democratic Caucus | |

| In office March 4, 1881 – March 3, 1885 | |

| Preceded by | William A. Wallace |

| Succeeded by | James B. Beck |

| United States Senator from Ohio | |

| In office March 4, 1879 – March 3, 1885 | |

| Preceded by | Stanley Matthews |

| Succeeded by | Henry B. Payne |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Ohio's 1st district | |

| In office March 4, 1857 – March 3, 1865 | |

| Preceded by | Timothy C. Day |

| Succeeded by | Benjamin Eggleston |

| Member of the Ohio Senate from the 1st district | |

| In office January 2, 1854 – January 6, 1856 Served with John Schiff, William Converse | |

| Preceded by | Edwin Armstrong Adam Riddle John Vattier |

| Succeeded by | Stanley Matthews George Holmes William Converse |

| Personal details | |

| Born | George Hunt Pendleton July 19, 1825 Cincinnati, Ohio, U.S. |

| Died | November 24, 1889 (aged 64) Brussels, Belgium |

| Resting place | Spring Grove Cemetery Cincinnati, Ohio, U.S. |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Spouse | Alice Key |

| Parent(s) | Jane Frances Hunt Pendleton Nathanael Greene Pendleton |

| Relatives | Francis Scott Key (father-in-law) |

| Education | University of Cincinnati Heidelberg University |

George Hunt Pendleton (July 19, 1825 – November 24, 1889)[1] was an American politician, lawyer and diplomat. He represented Ohio in both houses of Congress and was the unsuccessful Democratic nominee for Vice President of the United States in 1864.

After studying at the University of Cincinnati and Heidelberg University in Europe, Pendleton practiced law in his home town of Cincinnati, Ohio. He was the son of Congressman Nathanael G. Pendleton and the son-in-law of poet Francis Scott Key. After serving in the Ohio Senate, Pendleton won election to the United States House of Representatives. During the Civil War, he emerged as a leader of the Copperheads, a group of Democrats who favored peace with the Confederacy.[2] After the war, he opposed the Thirteenth Amendment and the Civil Rights Act of 1866.

The 1864 Democratic National Convention nominated a ticket of George B. McClellan, who favored continuing the war, and Pendleton, who opposed it. The ticket was defeated by the National Union ticket of Abraham Lincoln and Andrew Johnson, and Pendleton's term as a Congressman expired shortly thereafter. Pendleton was a strong contender for the presidential nomination at the 1868 Democratic National Convention, but was defeated by Horatio Seymour. After Pendleton lost the 1869 Ohio gubernatorial election, he temporarily left politics.

He served as the president of the Kentucky Central Railroad before returning to Congress. Pendleton won election to the U.S. Senate in 1879 and served a single term, becoming Chairman of the Senate Democratic Conference. After the assassination of President James A. Garfield, he wrote and helped pass the Pendleton Civil Service Reform Act of 1883. The act required many civil service hires to be based on merit rather than political connections. Passage of the act lost him support in Ohio and he was not nominated for a second term in the Senate. President Grover Cleveland appointed him as the ambassador to the German Empire. He served in that position until 1889, dying later that same year.

Early life

[edit]Pendleton was born in Cincinnati on July 19, 1825. He was the son of Jane Frances (née Hunt) Pendleton (1802–1839) and U.S. Representative Nathanael Greene Pendleton (1793–1861).[3]

He attended the local schools and Cincinnati College and the University of Heidelberg in Germany. Pendleton studied law and was admitted to the bar in 1847 and commenced practice in Cincinnati.[4]

Career

[edit]

Pendleton was elected as a member of the Ohio Senate, serving from 1854 to 1856. His father had been a member of the Ohio Senate from 1825 until 1827.[3] In 1854, he ran unsuccessfully for the Thirty-fourth United States Congress. Two years later, he was elected as a Democrat to the Thirty-fifth Congress and would be re-elected to the three following Congresses (March 4, 1857 – March 3, 1865). During his time in the House of Representatives, he was one of the managers appointed by the House of Representatives in 1862 to conduct the impeachment proceedings against West H. Humphreys, a US judge for several districts of Tennessee.

In the 1850s, Pendleton actively opposed measures to prohibit slavery in the Western United States.[2] A leading defender of slavery,[5] he was a leader of the "peace" faction of his party during the American Civil War, with close ties to the Copperheads. He voted against the Thirteenth Amendment, which outlawed slavery and involuntary servitude.[6]

National politics

[edit]Pendleton, a nationally prominent Extreme Peace Democrat, was nominated as the vice presidential running mate of George McClellan, a War Democrat, in the 1864 presidential election. McClellan, age 37 at the time of the convention, and Pendleton, age 39, are the youngest major party presidential ticket ever nominated in the United States. Their National Union opponents were President Lincoln and Andrew Johnson. McClellan and Pendleton lost, receiving about 45% of the popular vote and less than 10% of the electoral vote.

Since Pendleton was the Democratic vice-presidential nominee, he was not a candidate for re-election to the Thirty-ninth Congress. George E. Pugh, the Democrat nominated to run for Pendleton's seat, lost to Republican Benjamin Eggleston.

Out of office

[edit]Out of office for the first time in a decade, Pendleton ran for his old House seat in 1866 but lost. In 1868, he sought the Democratic Party's presidential nomination. He led for the first 15 ballots and was nearly the nominee, but his support disappeared and he lost to Horatio Seymour, primarily for his support of the "Ohio idea."[2] The following year, he was the Democratic nominee for Governor of Ohio and again lost, this time to Rutherford B. Hayes.[4]

Pendleton stepped away from politics, and in 1869, he became president of the Kentucky Central Railroad.[7]

Political comeback

[edit]In 1879, he made his comeback when he was elected as a Democrat to the United States Senate. During his only term, from 1881 to 1885, he served concurrently as the Chairman of the Democratic Conference. Following the 1881 assassination of James A. Garfield, he passed his most notable legislation, known as the Pendleton Act of 1883, requiring civil service exams for government positions. The Act helped put an end to the system of patronage in widespread use at the time, but it cost Pendleton politically, as many members of his own party preferred the spoils system. He was thus not renominated to the Senate.[4]

Later life

[edit]

Instead, President Grover Cleveland appointed him Envoy Extraordinary and Minister Plenipotentiary to Germany the year that he left office, which he served until April 1889. Five months later, during his return trip to the United States, he died in Brussels, Belgium.[4]

Beliefs

[edit]Pendleton had a very Jacksonian commitment to the Democratic Party as the best, perhaps the only, mechanism through which ordinary Americans could shape government policies. Mach (2007) argues that Pendleton's chief contribution was to demonstrate the Whig Party's willingness to use its power in government to achieve Jacksonian ideals.

While his Jacksonian commitment to states' rights and limited government made him a dissenter during the Civil War, what Mach calls Pendleton's Jacksonian "ardor to expand opportunities for ordinary Americans" was the basis for his leadership in civil service reform and his controversial plan to use greenbacks to repay the federal debt. What appeared to be a substantive ideological shift, Mach argues, represented Pendleton's pragmatic willingness to use new means to achieve old ends.

Personal life

[edit]

In 1846, Pendleton was married to Mary Alicia Key (1824–1886), the daughter of Francis Scott Key, the lawyer, author, and amateur poet who is best known today for writing a poem which later became the lyrics for the United States' national anthem, "The Star-Spangled Banner." Together, George and Alicia were the parents of:

- Sarah Pendleton (born in Ireland, about 1846)

- Francis Key Pendleton (1850–1930), who was born in Cincinnati and became prominent in New York society during the Gilded Age.[8][9]

- Mary Lloyd Pendleton (1852–1929), who was born in Cincinnati.

- Jane Francis Pendleton (1860–1950), who was born in the District of Columbia, April 22, 1860.[10]

- George Hunt Pendleton (1863–1868), who died young.

At the end of his life, Pendleton suffered a stroke.[11] Pendleton died in Brussels, Belgium on November 24, 1889.[1] He is interred in Spring Grove Cemetery, Cincinnati, Ohio.

Memorials

[edit]The city of Pendleton, Oregon, is named after him.[12]

The George H. Pendleton House in Cincinnati is a National Historical Landmark and was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1966.[13]

In popular culture

[edit]In Steven Spielberg's 2012 film, Lincoln, Pendleton is played by Peter McRobbie and portrayed as one of the most notable opponents of the Thirteenth Amendment and of the Civil Rights Act of 1866.

References

[edit]- ^ a b "DEATH OF A DIPLOMAT | END OF GEORGE H. PENDLETON'S CAREER.THE EX-MINISTER TO GERMANY DYING AT BRUSSELS—HIS LIFE WORK AT HOME AND ABROAD" (PDF). The New York Times. November 26, 1889. Retrieved 3 October 2018.

- ^ a b c Searles, Harry; Mangus, Mike (April 9, 2012). George Hunt Pendleton (July 19, 1825 – November 24, 1889). Ohio Civil War Central. Retrieved January 27, 2022.

- ^ a b "PENDLETON, Nathanael Greene - Biographical Information". bioguide.congress.gov. Biographical Directory of the United States Congress. Retrieved 3 October 2018.

- ^ a b c d "PENDLETON, George Hunt - Biographical Information". bioguide.congress.gov. Biographical Directory of the United States Congress. Retrieved 3 October 2018.

- ^ December 4, 2012. Pendleton namesake fought for slavery. East Oregonian. Retrieved January 27, 2022.

- ^ "Recognizing the Anniversary of the 13th Amendment (Extensions of Remarks)". Congressional Record. 151 (157). Government Printing Office: E2496–E2497. December 8, 2005.

- ^ Kentucky Central Railroad Company (1877). Charter of the Kentucky Central Railroad Company: To which is Added the General Laws of Kentucky Relating to Railroad Interests, and an Abstract of Decisions of the Court of Appeals Thereon. Also, Charters of the Maysville and Lexington Railroad Companies, North and Southern Divisions. Printed at the Western Methodist Book Concern. p. 7. Retrieved 3 October 2018.

- ^ McAllister, Ward (16 February 1892). "THE ONLY FOUR HUNDRED | WARD M'ALLISTER GIVES OUT THE OFFICIAL LIST. HERE ARE THE NAMES, DON'T YOU KNOW, ON THE AUTHORITY OF THEIR GREAT LEADER, YOU UNDER- STAND, AND THEREFORE GENUINE, YOU SEE" (PDF). The New York Times. Retrieved 26 March 2017.

- ^ Patterson, Jerry E. (2000). The First Four Hundred: Mrs. Astor's New York in the Gilded Age. Random House Incorporated. p. 217. ISBN 9780847822089. Retrieved 13 June 2018.

- ^ "RootsWeb's WorldConnect Project: Janet Ariciu family Bush". Wc.rootsweb.ancestry.com. Retrieved 2013-11-08.

- ^ "Name from History: The Pendletons led remarkable lives that shaped region, U.S. history". WCPO. 9 January 2017. Retrieved 16 June 2019.

- ^ "History of Pendleton". Pendleton, OR. Retrieved 2021-11-11.

- ^ "National Historic Landmark nomination for George H. Pendleton House". National Park Service. Retrieved 2018-03-20.

Sources

[edit]- Mach, Thomas S. "Gentleman George" Hunt Pendleton: Party Politics and Ideological Identity in Nineteenth-Century America, Kent State University Press, 2007, ISBN 978-0-87338-913-6, 317 pp. excerpt; also online review

Further reading

[edit]- Barreyre, Nicolas. “The Politics of Economic Crises: The Panic of 1873, the End of Reconstruction, and the Realignment of American Politics.” Journal of the Gilded Age and Progressive Era 10#4 (2011), pp. 403–23. online

- Shipley, Max L. “The Background and Legal Aspects of the Pendleton Plan.” Mississippi Valley Historical Review 24#3 1937, pp. 329–40. online

External links

[edit]- United States Congress. "George H. Pendleton (id: P000203)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress.

- George H. Pendleton at Find a Grave

- 1825 births

- 1889 deaths

- Politicians from Cincinnati

- Pendleton family

- American people of English descent

- Key family of Maryland

- Democratic Party members of the United States House of Representatives from Ohio

- Democratic Party United States senators from Ohio

- Civil service reform in the United States

- Ambassadors of the United States to Germany

- 1864 United States vice-presidential candidates

- Democratic Party (United States) vice presidential nominees

- Candidates in the 1868 United States presidential election

- Ohio state senators

- 19th-century American diplomats

- 19th-century American legislators

- 19th-century American railroad executives

- Ohio lawyers

- University of Cincinnati alumni

- Heidelberg University alumni

- People of Ohio in the American Civil War

- Burials at Spring Grove Cemetery

- American proslavery activists

- Progressivism in the United States

- History of racism in Ohio

- Copperheads (politics)