City Lights Bookstore

This article needs additional citations for verification. (October 2022) |

| City Lights Bookstore | |

|---|---|

City Lights Bookstore, 2023 | |

| General information | |

| Type | Commercial |

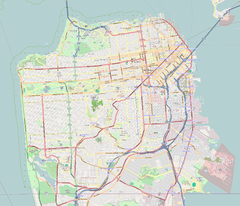

| Location | 261–271 Columbus Avenue San Francisco, California |

| Coordinates | 37°47′51″N 122°24′24″W / 37.797628°N 122.406575°W |

| Designated | 2001[1] |

| Reference no. | 228 |

City Lights is an independent bookstore-publisher combination in San Francisco, California, that specializes in world literature, the arts, and progressive politics. It also houses the nonprofit City Lights Foundation, which publishes selected titles related to San Francisco culture. It was founded in 1953 by poet Lawrence Ferlinghetti and Peter D. Martin[2] (who left two years later). Both the store and the publishers became widely known following the obscenity trial of Ferlinghetti for publishing Allen Ginsberg's influential collection Howl and Other Poems (City Lights, 1956). Nancy Peters started working there in 1971 and retired as executive director in 2007. In 2001, City Lights was made an official historic landmark. City Lights is located at 261 Columbus Avenue. While formally located in Chinatown, it self-identifies as part of immediately adjacent North Beach.

History

[edit]Founding and early years

[edit]City Lights was the inspiration of Peter D. Martin, who relocated from New York City to San Francisco in the 1940s to teach sociology. He first used City Lights, in homage to the Chaplin film, in 1952 as the title of a magazine, publishing early work by such key Bay Area writers as Philip Lamantia, Pauline Kael, Jack Spicer, Robert Duncan, and Ferlinghetti himself, as "Lawrence Ferling". A year later, Martin used the name to establish the first all-paperback bookstore in the U.S., at the time an audacious idea.[citation needed]

The site was a tiny storefront in the triangular Artigues Building located at 261 Columbus Avenue, near the intersection of Broadway in North Beach. Built on the ruins of a previous building destroyed in the fire following the 1906 earthquake, the building was designed by Oliver Everett in 1907 and named for its owners. City Lights originally shared the building with a number of other shops. It gradually gained more space whenever one of the other shops became vacant, and eventually occupied the entire building.[citation needed]

In 1953, as Ferlinghetti was walking past the Artigues Building, he encountered Martin out front hanging up a sign that announced a "Pocket Book Shop." He introduced himself as a contributor to Martin's magazine City Lights, and told him he had always wanted a bookstore. Before long he and Martin agreed to a partnership. Each man invested $500. Soon after they opened, they hired Shig Murao as a clerk. Murao worked without pay for the first few weeks, but eventually became manager of the store and was a key element in creating the unique feel of City Lights.[3] In 1955, Martin sold his share of the business to Ferlinghetti for $1000, moved to New York and started the New Yorker Bookstore which specialized in cinema.[citation needed]

In the late 1960s, Ferlinghetti hired Joseph Wolberg, former philosophy professor at SUNY Buffalo, to manage the bookstore. Wolberg is credited with organizing the once chaotically messy shelves and for convincing a cheap Ferlinghetti to install anti-shoplifting metal detectors. Through his connection to City Lights, Wolberg produced records for Beat poets such as Charles Bukowski and Shel Silverstein.

The logo for City Lights Bookstore is a medieval guild mark, chosen by Ferlinghetti, from Rudolf Koch's The Book of Signs.[4][5]

1970s and 1980s

[edit]In 1970, City Lights hired Paul Yamazaki, an activist who had been jailed during protests for Black studies and Ethnic studies departments at San Francisco State University. Yamazaki would continue working at the bookstore for over fifty years, and in 2023 was awarded the National Book Foundation's Literarian Award for Outstanding Service to the Literary Community.[6]

In 1971, Ferlinghetti persuaded Nancy Peters – who was working at the Library of Congress – to join in a project with him, after which she began full-time work at City Lights.[7] She said:

When I joined City Lights in 1971, and started working with Lawrence, it was clear that it had been very much a center of protest, for people with revolutionary ideas and people who wanted to change society. And when I first began working at the little editorial office up on Filbert and Grant, people that Lawrence had known through the whole decade of the '60s were dropping in all the time, like Paul Krassner, Tim Leary, people who were working with underground presses and trying to provide an alternative to mainstream media. This was a period of persecution, and FBI infiltration of those presses.[8]

In 1984, the business was in a financial crisis and Peters became a co-owner of it.[7] Ferlinghetti credits her for the subsequent survival and growing success of the business.[9] In 1999, with Ferlinghetti, she bought the building they worked in.[10]

2000s

[edit]In 2001, the San Francisco Board of Supervisors made City Lights an official historic landmark – the first time this had been granted to a business, rather than a building – citing the organization for "playing a seminal role in the literary and cultural development of San Francisco and the nation." It recognized the bookstore as "a landmark that attracts thousands of book lovers from all over the world because of its strong ambiance of alternative culture and arts", and it acknowledged City Lights Publishers for its "significant contribution to major developments in post-World War II literature."

The building itself, with its clerestory windows and small mezzanine balcony, also qualified as a city landmark because of its "distinctive characteristics typical of small commercial buildings constructed following the 1906 earthquake and fire." The landmark designation mandates the preservation of certain external features of the building and its immediate surroundings. Peters commented (referring to the effect of dotcom and computer firms), "The old San Francisco is under attack to the point where it's disappearing."[11]

By 2003, the store had 15 employees.[12] Peters estimated that the year's profits would be only "maybe a thousand dollars."[13] In 2007, after 23 years as executive director, she stepped down from the post, which was filled by Elaine Katzenberger; Peters remained on the board of directors.[9] Peters said of her work at City Lights:

When I started working here we were in the middle of the Vietnam War, and now it's Iraq. This place has been a beacon, a place of learning and enlightenment.[9]

Present

[edit]

City Lights sells a curated selection of new books, specializing in literature, cultural studies, world history, and politics. It offers three floors of new-release hardcovers and paperbacks from all major publishers, as well as a large selection of titles from smaller, independent publishers. It hosts weekly events in its City Lights LIVE programming series, which switched to virtual events in 2020 due to the pandemic. City Lights is a member of the American Booksellers Association.[14]

Publishing

[edit]In 1955, Ferlinghetti launched City Lights Publishers with his own Pictures of the Gone World, the first number in the Pocket Poets Series. This was followed in quick succession by Thirty Spanish Poems of Love and Exile translated by Kenneth Rexroth and Poems of Humor & Protest by Kenneth Patchen, but it was the impact of the fourth volume, Howl and Other Poems (1956) by Allen Ginsberg that brought national attention to the author and publisher.

City Lights Journal published poems of the Indian Hungry generation writers when the group faced police case in Kolkata. The group got worldwide publicity thereafter.

Apart from Ginsberg's seven collections, a number of the early Pocket Poets volumes brought out by Ferlinghetti have attained the status of classics, including True Minds by Marie Ponsot (1957), Here and Now by Denise Levertov (1958), Gasoline (1958) by Gregory Corso, Selected Poems by Robert Duncan (1959), Lunch Poems (1964) by Frank O'Hara, Selected Poems (1967) by Philip Lamantia, Poems to Fernando (1968) by Janine Pommy Vega, Golden Sardine (1969) by Bob Kaufman, and Revolutionary Letters (1971) by Diane di Prima.

In 1967 the publishing operation moved to 1562 Grant Avenue. Dick McBride ran this part of the business with his brother Bob McBride and Martin Broadley for several years.[15]

In 1971, Nancy Peters joined Ferlinghetti as co-editor and publisher. He praised her as "one of the best literary editors in the country.".[16] Presently, the publisher is Elaine Katzenberger, who is also the director of the bookstore.

Over the years, the press has published a wide range of poetry and prose, fiction and nonfiction, and works in translation. In addition to books by Beat Generation authors, the press publishes literary work by such authors as Charles Bukowski, Georges Bataille, Rikki Ducornet, Paul Bowles, Sam Shepard, Andrei Voznesensky, Nathaniel Mackey, Alejandro Murguía, Pier Paolo Pasolini, Ernesto Cardenal, Daisy Zamora, Guillermo Gómez-Peña, Juan Goytisolo, Anne Waldman, André Breton, Kamau Daáood, Masha Tupitsyn, and Rebecca Brown. In 1965, the press published an anthology of texts by Antonin Artaud, edited by Jack Hirschman.[17]

In 2014, the press published its first New York Times bestselling book, Rad American Women A-Z, the press's first book for children, by Kate Schatz with illustrations by Miriam Klein Stahl. Since then, other critically acclaimed books of fiction, nonfiction, and poetry include Man Alive by Thomas Page McBee, Notes on the Assemblage by Juan Felipe Herrera (who was U.S. Poet Laureate at the time), Dated Emcees by Chinaka Hodge, an anniversary edition of The Gilda Stories by Jewelle Gomez, Incidents of Travel in Poetry by Frank Lima, Retablos by Octavio Solis, Poso Wells by Gabriela Alemán, Under the Dome by Jean Daive, and Funeral Diva by Pamela Sneed, among others. The press has also published two books by Tongo Eisen-Martin, Poet Laureate of San Francisco.

Associated from the outset with radical left-wing politics and issues of social justice, City Lights has in recent years augmented its list of political non-fiction, publishing books by Angela Y. Davis, Noam Chomsky, Michael Parenti, Howard Zinn, Mumia Abu-Jamal, Ward Churchill, Tim Wise, Roy Scranton, John Gibler, Todd Miller, Clarence Lusane, Ralph Nader, Henry A. Giroux, and Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz.

Howl

[edit]

Ferlinghetti had heard Ginsberg read Howl in 1955 at the Six Gallery; the next day, he offered to publish it along with other shorter poems. William Carlos Williams — who was Ginsberg's childhood Pediatrician and himself a future Pocket Poet with a 1957 edition of his early modernist classic, Kora in Hell (1920) — was recruited for an introduction, perhaps to lend literary justification to Howl's depictions of drug use and homosexuality. Prior to publication, Ferlinghetti had asked, and received, assurance from the American Civil Liberties Union that the organization would defend him, should he be prosecuted for obscenity.

Published in November 1956, Howl was not long in generating controversy. In March 1957, local Collector of Customs Chester MacPhee seized a shipment from England of the book's second printing on grounds of obscenity, but he was compelled to release the books when federal authorities refused to confirm his charge. But the troubles were just beginning, for in June of that year, local police raided City Lights Bookstore and arrested store manager Shigeyoshi Murao on the charge of offering an obscene book for sale. Ferlinghetti, then in Big Sur, turned himself in on his return to San Francisco. Both faced a possible $500 fine and a 6-month sentence. (Ginsberg was in Tangiers at the time, and not charged.) The ACLU posted bail, assigned defense counsel Albert Bendich to the case, and secured the pro bono services of famous criminal defense lawyer J. W. Ehrlich.

The municipal court trial, presided over by Judge Clayton W. Horn, ran from August 16 to September 3, 1957. The charges against Murao were dismissed since it couldn't be proved that he knew what was in the book. Then, during the trial of Ferlinghetti, respected writers and professors testified for the defense. Judge Horn rendered his precedent-setting verdict, declaring that Howl was not obscene and that a book with "the slightest redeeming social importance" merits First Amendment protection. Horn's decision established the precedent that paved the way for the publication of such hitherto banned books as D. H. Lawrence's Lady Chatterley's Lover and Henry Miller's Tropic of Cancer. The media attention resulting from the trial stimulated national interest, and, by 1958, there were 20,000 copies in print. Today there are over a million. Ginsberg continued to publish his major books of poetry with the press for the next 25 years. Even after the publication by Harper & Row of his Collected Poems in 1980, he would continue his warm association with City Lights, which served as his local base of operations, for the rest of his life.

Notes and references

[edit]- ^ "City of San Francisco Designated Landmarks". City of San Francisco. Archived from the original on March 25, 2014. Retrieved October 21, 2012.

- ^ Veltman, Chloe (March 15, 2019). "Literary Icon Lawrence Ferlinghetti Marks His 100th Birthday With New Work". KQED. Retrieved March 17, 2019.

- ^ Shawn Hubler, "City Lights Illuminates the Past", Los Angeles Times, May 27, 2003.

- ^ "City Lights Bookstore Tour". City Lights Books. City Lights Booksellers & Publishers. Archived from the original on April 23, 2021. Retrieved May 25, 2021.

You'll also find the City Lights logo here and there around the store; it's a medieval guild mark Ferlinghetti chose from the Koch Book of Signs.

- ^ Koch, Rudolf (1955). The book of signs (Das Zeichenbuch) : which contains all manner of symbols used from the earliest times to the Middle Ages by primitive peoples and early Christians. New York: Dover Publications. ISBN 9780486201627. OCLC 509534. Retrieved May 25, 2021.

collected, drawn and explained by Rudolf Koch ; translated from the German by Vyvyan Holland. An unabridged republication of the English translation first published ... in 1930.

- ^ Howard, Rachel (January 5, 2024). "'A legend in the literary world' keeps S.F.'s City Lights shining". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved January 6, 2024.

- ^ a b Morgan, Bill, "City Lights bookshop tour", City Lights. Retrieved August 7, 2007.

- ^ "And the beat goes on", San Francisco Chronicle, 9 June 2003. Retrieved 7 August 2007.

- ^ a b c Lynell, George (2007), "City Lights Books", Los Angeles Times, April 22, 2007. Retrieved August 7, 2007.

- ^ "City Lights: 50 candles", Chicago Sun-Times on findarticles.com, June 22, 2003. Retrieved August 7, 2007.

- ^ David, Simon (2001), "'Beat city' fights dotcom gold rush", The Daily Telegraph, June 19, 2001. Retrieved August 7, 2007.

- ^ Lara, Adair (2003), "Literary Light", San Francisco Chronicle, June 5, 2003. Retrieved August 7, 2007.

- ^ Hubler, Shawn (2003), "At 50, City Lights illuminates the past", Oakland Tribune/Los Angeles Times on findarticles.com, June 15, 2003. Retrieved August 7, 2007.

- ^ ABA Bookseller Member Directory

- ^ Ferlinghetti, L & Morgan, B "The Beat Generation in San Francisco: A Literary Tour" City Lights Books, 2003 ISBN 0-87286-417-0

- ^ González, Ray (2003) "Tracing the public surface", The Bloomsbury Review, Vol. 23, No. 2, 2003. Retrieved August 7, 2007.

- ^ Artaud, Antonin. Antonin Artaud Anthology, edited by Jack Hirschman. San Francisco: City Lights, 1965. ISBN 978-0-87286-000-1

External links

[edit]- Official website

- Landmark status likely for beatnik-era bookstore, a June 2001 CNN article

- And the Beats Go On, a June 2001 article from the San Francisco Chronicle

- Poetry Landmark: The City Lights Bookstore Archived September 12, 2012, at the Wayback Machine, from the website of the Academy of American Poets

- Guide to the records of City Lights Books at The Bancroft Library

- [1] Paul Yamazaki, Chief Buyer at the Bookshop had a conversation with Rishabh Chaddha(Contributing Writer/Correspondent) about Bookselling Business Ecosystem. When and how City Lights Books came into existence, how it became such a historical landmark. What was the mission and vision Lawrence Ferlinghetti and Peter Martin had projected when they founded this book heaven.

- City Lights Books

- 1953 establishments in California

- American companies established in 1953

- Beat Generation

- Book publishing companies based in San Francisco

- Bookstores established in the 20th century

- Bookstores in the San Francisco Bay Area

- Buildings and structures in San Francisco

- Chinatown, San Francisco

- Independent bookstores of the United States

- Retail buildings in California

- Retail companies established in 1953

- San Francisco Designated Landmarks

- Political book publishing companies

- Small press publishing companies

- Literary publishing companies