Epistle to the Philippians

| Part of a series on |

| Books of the New Testament |

|---|

|

| Part of a series of articles on |

| Paul in the Bible |

|---|

|

The Epistle to the Philippians[a] is a Pauline epistle of the New Testament of the Christian Bible. The epistle is attributed to Paul the Apostle and Timothy is named with him as co-author or co-sender. The letter is addressed to the Christian church in Philippi.[3] Paul, Timothy, Silas (and perhaps Luke) first visited Philippi in Greece (Macedonia) during Paul's second missionary journey from Antioch, which occurred between approximately 50 and 52 AD. In the account of his visit in the Acts of the Apostles, Paul and Silas are accused of "disturbing the city".[4]

There is a general consensus that Philippians consists of authentically Pauline material, and that the epistle is a composite of multiple letter fragments from Paul to the church in Philippi.[5][6]: 17 These letters could have been written from Ephesus in 52–55 AD or Caesarea Maritima in 57–59, but the most likely city of provenance is Rome, around 62 AD, or about 10 years after Paul's first visit to Philippi.[7]

Composition

[edit]

Starting in the 1960s, a consensus emerged among biblical scholars that Philippians was not written as one unified letter, but rather as a compilation of fragments from three separate letters from Paul to the church in Philippi.[6]: 17 According to Philip Sellew, Philippians contains the following letter fragments:

- Letter A consists of Philippians 4:10–20. It is a short thank-you note from Paul to the Philippian church, regarding gifts they had sent him.[8]

- Letter B consists of Philippians 1:1–3:1, and may also include 4:4–9 and 4:21–23.

- Letter C consists of Philippians 3:2–4:1, and may also include 4:2–3. It is a testament to Paul's rejection of all worldly things for the sake of the gospel of Jesus.[6]: 19

In support of the idea that Philippians is a composite work, Sellew pointed to the abrupt shifts in tone and topic within the text. There also seem to be chronological inconsistencies from one chapter to the next concerning Paul's associate Epaphroditus:

Another argument against unity has been found in the swiftly changing fortunes of Epaphroditus: this associate of Paul is at the point of death in chapter two (Phil 2:25–30), where seemingly he has long been bereft of the company of the Philippian Christians; Paul says that he intended to send him back to Philippi after this apparently lengthy, or at least near-fatal separation. Two chapters later, however, at the end of the canonical letter, Paul notes that Epaphroditus had only now just arrived at Paul's side, carrying a gift from Philippi, a reference found toward the close of the "thank-you note" as a formulaic acknowledgement of receipt at Phil 4:18.

— Philip Sellew[6]: 18

These letter fragments likely would have been edited into a single document by the first collector of the Pauline corpus, although there is no clear consensus among scholars regarding who this initial collector may have been, or when the first collection of Pauline epistles may have been published.[6]: 26

Today, a number of scholars believe that Philippians is a composite of multiple letter fragments. According to the theologian G. Walter Hansen, "The traditional view that Philippians was composed as one letter in the form presented in the NT [New Testament] can no longer claim widespread support."[5]

Regardless of the literary unity of the letter, scholars agree that the material that was compiled into the Epistle to the Philippians was originally composed in Koine Greek, sometime during the 50s or early 60s AD.[9]

Place of writing

[edit]

It is uncertain where Paul was when he wrote the letter(s) that make up Philippians. Internal evidence in the letter itself points clearly to it being composed while Paul was in custody,[10] but it is unclear which period of imprisonment the letter refers to. If the testimony of the Acts of the Apostles is to be trusted, candidates would include the Roman imprisonment at the end of Acts,[11] and the earlier Caesarean imprisonment.[12] Any identification of the place of writing of Philippians is complicated by the fact that some scholars view Acts as being an unreliable source of information about the early Church.[13]

Jim Reiher has suggested that the letters could stem from the second period of Roman imprisonment attested by early church fathers.[14][15] The main reasons suggested for a later date include:

- The letter's highly developed Ecclesiology

- An impending sense of death permeating the letter

- The absence of any mention of Luke in a letter to Luke's home church (when the narrative in Acts clearly suggests that Luke was with Paul in his first Roman imprisonment)

- A harsher imprisonment than the open house arrest of his first Roman imprisonment

- A similar unique expression that is shared only with 2 Timothy

- A similar disappointment with co-workers shared only with 2 Timothy

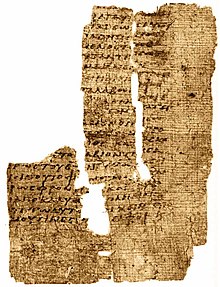

Surviving early manuscripts

[edit]The original manuscript or manuscripts of the epistle are lost, and the text of surviving copies varies. The earliest surviving manuscripts were made centuries later, and include complete and partial copies:

- Papyrus 16 (3rd century)[16]

- Codex Vaticanus (AD 325–350)

- Codex Sinaiticus (330–360)

- Codex Alexandrinus (400–440)

- Codex Ephraemi Rescriptus (c. 450)

- Codex Freerianus (c. 450)[17]

- Codex Claromontanus (c. 550)

Contents

[edit]In Chapters 1 and 2 of Philippians (Letter B), Paul sends word to the Philippians of his upcoming sentence in Rome and of his optimism in the face of death,[18] along with exhortations to imitate his capacity to rejoice in the Lord despite one's circumstances.[19] Paul assures the Philippians that his imprisonment is actually helping to spread the Christian message, rather than hindering it.[20] He also expresses gratitude for the devotion and heroism of Epaphroditus, who the Philippian church had sent to visit Paul and bring him gifts.[21] Some time during his visit with Paul, Epaphroditus apparently contracted some life-threatening debilitating illness.[22] But he recovers before being sent back to the Philippians.

In Chapter 3 (Letter C), Paul warns the Philippians about those Christians who insist that circumcision is necessary for salvation. He testifies that while he once was a devout Pharisee and follower of the Jewish law, he now considers these things to be worthless and worldly compared to the gospel of Jesus.[23]

In Chapter 4, Paul urges the Philippians to resolve conflicts within their fellowship.[24] In the latter part of the chapter (Letter A), Paul expresses his gratitude for the gifts that the Philippians had sent him, and assures them that God will reward them for their generosity.[25]

Throughout the epistle there is a sense of optimism. Paul is hopeful that he will be released, and on this basis he promises to send Timothy to the Philippians for ministry,[26] and also expects to pay them a personal visit.[27]

Christ poem

[edit]Chapter 2 of the epistle contains a famous poem describing the nature of Christ and his act of redemption:

Who, though he was in the form of God,

- Did not regard being equal with God

- Something to be grasped after.

But he emptied himself

- Taking on the form of a slave,

- And coming in the likeness of humans.

And being found in appearance as a human

- He humbled himself

- Becoming obedient unto death— even death on a cross.

Therefore God highly exalted him

- And bestowed on him the name

- That is above every name,

That at the name of Jesus

- Every knee should bow

- Of those in heaven, and on earth, and under the earth.

And every tongue should confess

- That Jesus Christ is Lord

- To the glory of God the Father.

— Philippians 2:5–11, translated by Bart D. Ehrman[28]

Due to its unique poetic style, Bart D. Ehrman suggests that this passage constitutes an early Christian poem that was composed by someone else prior to Paul's writings, as early as the mid-late 30s AD and was later used by Paul in his epistle. While the passage is often called a "hymn", some scholars believe this to be an inappropriate name since it does not have a rhythmic or metrical structure in the original Greek.[28] This theory was first proposed by German Protestant theologian Ernst Lohmeyer in 1928, and this "has come to dominate both exegesis of Philippians and study of early Christology and credal formulas".Murray, Robert, SJ (2007). "69. Philippians". In Barton, John; Muddiman, John (eds.). The Oxford Bible Commentary (first (paperback) ed.). Oxford University Press. p. 1180. ISBN 978-0199277186. Retrieved February 6, 2019.{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

Incarnation Christology

[edit]The Christ poem is significant because it strongly suggests that there were very early Christians who understood Jesus to be a pre-existent celestial being, who chose to take on human form, rather than a human who was later exalted to a divine status.[29][28]

While the author of the poem did believe that Jesus existed in heaven before his physical incarnation, there is some debate about whether he was believed to be equal to God the Father prior to his death and resurrection. This largely depends on how the Greek word harpagmon (ἁρπαγμόν, accusative form of ἁρπαγμός) is translated in verse 6 ("Something to be grasped after / exploited"). If harpagmon is rendered as "something to be exploited," as it is in many Christian Bible translations, then the implication is that Christ was already equal to God prior to his incarnation. But Bart Ehrman and others have argued that the correct translation is in fact "something to be grasped after," implying that Jesus was not equal to God before his resurrection. Outside of this passage, harpagmon and related words were almost always used to refer to something that a person doesn't yet possess but tries to acquire.[28]

It is widely agreed by interpreters, however, that the Christ poem depicts Jesus as equal to God after his resurrection. This is because the last two stanzas quote Isaiah 45:22–23:[30] ("Every knee shall bow, every tongue confess"), which in the original context clearly refers to God the Father.[28] Some scholars argue that Philippians 2:6–11 identifies Jesus with God from his pre-existence on the basis that allusions to Isaiah 45:22–23 are present all throughout the poem.[31]

Outline

[edit]

- I. Preface (1:1–11)[32]

-

- A. Salutation (1:1–2)

- B. Thanksgiving for the Philippians’ Participation in the Gospel (1:3–8)

- C. Prayer for the Philippians’ Discerning Love to Increase until the Day of Christ (1:9–11)

- II. Paul’s Present Circumstances (1:12–26)

-

- A. Paul’s Imprisonment (1:12–13)

- B. The Brothers’ Response (1:14–17)

- C. Paul’s Attitude (1:18–26)

- III. Practical Instructions in Sanctification (1:27–2:30)

-

- A. Living Boldly as Citizens of Heaven (1:27–1:30)

- B. Living Humbly as Servants of Christ (2:1–11)

-

- 1. The Motivation to Live Humbly (2:1–4)

- 2. The Model of Living Humbly (2:5–11)

-

- a. Christ’s Emptying (2:5–8)

- b. Christ’s Exaltation (2:9–11)

- C. Living Obediently as Children of God (2:12–18)

-

- 1. The Energizing of God (2:12–13)

- 2. The Effect on the Saints (2:14–18)

- D. Examples of Humble Servants (2:19–30)

-

- 1. The Example of Timothy (2:19–24)

- 2. The Example of Epaphroditus (2:25–30)

- IV. Polemical Doctrinal Issues (3:1–4:1)

-

- A. The Judaizers Basis: The Flesh (3:1–6)

- B. Paul’s Goal: The Resurrection (3:7–11)

- C. Perfection and Humility (3:12–16)

- D. Paul as an Example of Conduct and Watchfulness (3:17–4:1)

- V. Postlude (4:2–23)

-

- A. Exhortations (4:2–9)

-

- 1. Being United (4:2–3)

- 2. Rejoicing without Anxiety (4:4–7)

- 3. Thinking and Acting Purely (4:8–9)

- B. A Note of Thanks (4:10–20)

-

- 1. Paul’s Contentment (4:10–13)

- 2. The Philippians’ Gift (4:14–18)

- 3. God’s Provision (4:19–20)

- C. Final Greetings (4:21–23)

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ ESV Pew Bible. Wheaton, IL: Crossway. 2018. p. 980. ISBN 978-1-4335-6343-0. Archived from the original on June 3, 2021.

- ^ "Bible Book Abbreviations". Logos Bible Software. Archived from the original on April 21, 2022. Retrieved April 21, 2022.

- ^ Phil 1:1

- ^ Acts 16:20

- ^ a b Hansen, Walter (2009). The Letter to the Philippians. Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company. p. 15. ISBN 978-1-84474-403-9.

- ^ a b c d e Sellew, Philip (January 1994). ""Laodiceans" and the Philippians Fragments Hypothesis". Harvard Theological Review. 87 (1): 17–28. doi:10.1017/S0017816000031618. JSTOR 1509846. S2CID 163252743.

- ^ Harris, Stephen L., Understanding the Bible. Palo Alto: Mayfield. 1985.

- ^ Phil 4:17

- ^ Bird, Michael F.; Gupta, Nijay K. (2020). Philippians. New Cambridge Bible Commentary. Cambridge University Press. p. 20. ISBN 978-1-108-47388-0.

- ^ Phil 1:7,13

- ^ Acts 28:30–31

- ^ Acts 23–26

- ^ Hornik, Heidi J.; Parsons, Mikeal C. (2017). The Acts of the Apostles through the centuries (1st ed.). John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. ISBN 9781118597873. In the words of Hornik and Parsons, "Acts must be carefully sifted and mined for historical information." (pg. 10)

- ^ Clement of Rome (late 1st century) makes a reference to the ministry of Paul after the end of Acts. Clement, To the Corinthians, 5. In J. B. Lightfoot (ed), The Apostolic Fathers (Michigan: Baker Book House, 1978) 15. The author of the Muratorian Canon (late 2nd century) says that Luke recorded mostly that which he himself witnessed and therefore that is why he did not include ‘the journey of Paul, when he went from the city – Rome – to Spain.’ The Muratoriun Canon. 2. The apocryphal Acts of Peter makes reference to the tradition that Paul reached Spain. Paul is described in prison in Rome, receiving a vision from God that he would go to Spain. Acts of Peter, Verscelli Acts 1 and 3. Eusebius (early 300’s) recorded that Paul did more ministry after his first jail time in Rome. Eusebius, Ecclesiastical History, II, 22, 1–8, in Philip Schaff and Henry Wace (editors), A Select Library of Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers of the Christian Church 2nd series. Vol.1. Eusebius: Church History, Life of Constantine the Great, and Oration in Praise of Constantine (Edinburgh: Eerdmans, 1997) 124–125.

- ^ Jim Reiher, “Could Philippians have been written from the Second Roman Imprisonment?” Evangelical Quarterly. Vol. LXXXIV. No. 3 July 2012. pp. 213–233. This article summarises the other theories, and offers examples of different scholars who adhere to different theories, but presents a different option for consideration.

- ^ Comfort, Philip W.; David P. Barrett (2001). The Text of the Earliest New Testament Greek Manuscripts. Wheaton, Illinois: Tyndale House Publishers. p. 93. ISBN 978-0-8423-5265-9.

- ^ Nestle-Aland, Novum Testamentum Graece, Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft, p. 610.

- ^ Phil 1:18b–26

- ^ Phil 2:14–18

- ^ Phil 1:12–15

- ^ Phil 2:25–30

- ^ Phil 2:26–27

- ^ Phil 3:2–10

- ^ Phil 4:2–3

- ^ Phil 4:15–20

- ^ Phil 2:19–23

- ^ Phil 2:24

- ^ a b c d e Ehrman, Bart D. (2014). "7. Jesus as God on Earth: Early Incarnation Christologies". How Jesus Became God: The Exaltation of a Jewish Preacher from Galilee. HarperOne. ISBN 978-0-0617-7819-3.

- ^ Martin, Ralph P. (1997). Philippians 2:5–11 in Recent Interpretation & in the Setting of Early Christian Worship (2nd ed.). Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press. pp. vii–ix. ISBN 0-8308-1894-4.

- ^ Isaiah 45:22–23

- ^ Hill, Wesley (2015). Paul and the Trinity: Persons, Relations, and the Pauline Letters. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. p. 96. ISBN 978-0-8028-6964-7.

- ^ "11. Philippians: Introduction, Argument, and Outline". Bible.org.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Easton, Matthew George (1897). "Philippians, Epistle to the". Easton's Bible Dictionary (New and revised ed.). T. Nelson and Sons.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Easton, Matthew George (1897). "Philippians, Epistle to the". Easton's Bible Dictionary (New and revised ed.). T. Nelson and Sons.

Further reading

[edit]- Abrahamsen, Valerie (March 1988). "Christianity and the Rock Reliefs at Philippi". Biblical Archaeologist. 51 (1): 46–56. doi:10.2307/3210038. JSTOR 3210038. S2CID 195040919.

- Barclay, William. 1975. The Letters to the Philippians, Colossians, and Thessalonians. Rev. ed. Daily Bible Study Series. Louisville, Ky.: Westminster.

- Barnes, Albert. 1949. Ephesians, Philippians, and Colossians. Enlarged type edition. Edited by Robert Frew. Grand Rapids, Mich.: Baker.

- Black, David A. 1995. "The Discourse Structure of Philippians: A Study in Textlinquistics." Novum Testamentum 37.1 (Jan.): 16–49

- Blevins, James L. 1980. "Introduction to Philippians." Review and Expositor 77 (Sum.): 311–325.

- Brooks, James A. 1980. "Introduction to Philippians." Southwestern Journal of Theology 23.1 (Fall): 7–54.

- Bruce, Frederick F. 1989. Philippians. New International Biblical Commentary. New Testament Series. Edited by W. Ward Gasque. Peabody, Mass.: Hendrickson, 2002.

- Burton, Ernest De Witt. 1896. "The Epistles of the Imprisonment." Biblical World 7.1: 46–56.

- Elkins, Garland. 1976. "The Living Message of Philippians." pp. 171–180 in The Living Messages of the Books of the New Testament. Edited by Garland Elkins and Thomas B. Warren. Jonesboro, Ark.: National Christian.

- Garland, David E. 1985. "The Composition and Unity of Philippians: Some Neglected Literary Factors." Novum Testamentum 27.2 (April): 141–173.

- Hagelberg, Dave. 2007. Philippians: An Ancient Thank You Letter – A Study of Paul and His Ministry Partners' Relationship. English ed. Metro Manila: Philippine Challenge.

- Hawthorne, Gerald F. 1983. Philippians. Word Biblical Commentary 43. Edited by Bruce Metzger. Nashville, Tenn.: Nelson.

- Herrick, Greg. "Introduction, Background, and Outline to Philippians." Bible.org.

- Jackson, Wayne. 1987. The Book of Philippians: A Grammatical and Practical Study. Abilene, Tex.: Quality.

- Kennedy, H. A. A. 1900. "The Epistle to the Philippians." Expositor's Greek Testament. Vol. 3. Edited by W. Robertson Nicoll. New York, NY: Doran.

- Lenski, Richard C. H. 1937. The Interpretation of St. Paul's Epistles to the Galatians, to the Ephesians, and to the Philippians. Repr. Peabody, Mass.: Hendrickson, 2001.

- Lipscomb, David and J.W. Shepherd. 1968. Ephesians, Philippians, and Colossians. Rev. ed. Edited by J.W. Shepherd. Gospel Advocated Commentary. Nashville, Tenn.: Gospel Advocate.

- Llewelyn, Stephen R. 1995. "Sending Letters in the Ancient World: Paul and the Philippians." Tyndale Bulletin 46.2: 337–356.

- Mackay, B. S. 1961. "Further Thoughts on Philippians." New Testament Studies 7.2 (Jan.): 161–170.

- Martin, Ralph P. 1959. The Epistle of Paul to the Philippians. Tyndale New Testament Commentaries. Ed. By R.V.G. Tasker. Grand Rapids, Mich.: Eerdmans, 1977.

- Martin, Ralph P. 1976. Philippians. New Century Bible Commentary. New Testament. Edited by Matthew Black. Repr. Grand Rapids, Mich.: Eerdmans.

- McAlister, Bryan. 2011. "Introduction to Philippians: Mindful of How We Fill Our Minds." Gospel Advocate 153.9 (Sept.): 12–13

- Mule, D. S. M. (1981). The Letter to the Philippians. Cook Book House.

- Müller, Jacobus J. 1955. The Epistle of Paul to the Philippians. New International Commentary on the New Testament. Ed. By Frederick F. Bruce. Grand Rapids, Mich.: Eerdmans, 1991.

- Pelaez, I. N. (1970). Epistle on the Philippians. Angel & Water;reprint, Angels new books, ed. Michael Angelo. (1987). Peabody, MA: Hendrickson.

- Dictionary of Paul and His Letters, s.v. "Philippians, Letter to the"

- Reicke, Bo. 1970. "Caesarea, Rome, and the Captivity Epistles." pp. 277–286 in Apostolic History and the Gospel: Biblical and Historical Essays Presented to F. F. Bruce. Edited by W. Ward Gasque and Ralph P. Martin. Exeter: Paternoster Press.

- Roper, David. 2003. "Philippians: Rejoicing in Christ." BibleCourses.com. Accessed: 3 Sept. 2011.

- Russell, Ronald. 1982. "Pauline Letter Structure in Philippians." Journal of the Evangelical Theological Society 25.3 (Sept.): 295–306.

- Sanders, Ed. 1987. "Philippians." pp. 331–339 in New Testament Survey. Edited by Don Shackelford. Searcy, Ark.: Harding University.

- Sergio Rosell Nebreda, Christ Identity: A Social-Scientific Reading of Philippians 2.5–11 (Göttingen, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2011) (Forschungen zur Religion und Literatur des Alten und Neuen Testaments, 240).

- Swift, Robert C. 1984. "The Theme and Structure of Philippians." Bibliotheca Sacra 141 (July): 234–254.

- Synge, F.C. 1951. Philippians and Colossians. Torch Bible Commentaries. Edited by John Marsh, David M. Paton, and Alan Richardson. London: SCM, 1958.

- Thielman, Frank. 1995. Philippians. NIV Application Commentary. General Editor. Terry Muck. Grand Rapids, Mich.: Zondervan.

- Vincent, Marvin R. 1897. The Epistle to the Philippians and to Philemon. International Critical Commentary. Ed. By Samuel R. Driver, Alfred Plummer, Charles A. Briggs. Edinburgh: Clark, 1902.

- Vincent, Marvin R. Vincent's Word Studies in the New Testament. 4 vols. Peabody, Mass.: Hendrickson, n.d.

- Wallace, Daniel B. "Philippians: Introductions, Argument, and Outline." Bible.org.

- Walvoord, John F. 1971. Philippians: Triumph in Christ. Everyman's Bible Commentary. Chicago, Ill.: Moody.

External links

[edit]Online translations of the Epistle to the Philippians:

- Online Bible at GospelHall.org

Bible: Philippians public domain audiobook at LibriVox Various versions

Bible: Philippians public domain audiobook at LibriVox Various versions

Online Study of Philippians:

- Letter to the Philippians Online Reading Room: Commentaries and other resources (Tyndale Seminary)

- Letter to the Philippians Online Reading Room: Commentaries and other resources (BiblicalStudies.org.uk)

- Letter to the Philippians Online Reading Room Archived 2017-04-23 at the Wayback Machine: Commentaries and other resources (NTGateway.com)

- Letter to the Philippians Online Reading Room: Commentaries and other resources (TextWeek.com)

Related articles:

- Bible.org introduction to Philippians

- Sermons on Philippians

- Heeren, Achille Vander (1911). . Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 12.

- Moffatt, James (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 21 (11th ed.). pp. 390–392.