Readjuster Party

Readjuster Party | |

|---|---|

| |

| Leader | William Mahone Harrison H. Riddleberger |

| Founded | 1877 |

| Dissolved | 1895 |

| Split from | Democratic Party |

| Merged into | Republican Party[1] |

| Ideology | Progressivism Reformism Modernization Populism Racial integration |

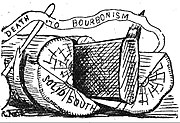

The Readjuster Party was a bi-racial state-level political party formed in Virginia across party lines in the late 1870s during the turbulent period following the Reconstruction era that sought to reduce outstanding debt owed by the state.[2] Readjusters aspired "to break the power of wealth and established privilege"[3] among the planter elite of whites in the state and to promote public education. The party's program attracted support among both white people and African-Americans.

The party was led by Harrison H. Riddleberger of Woodstock, an attorney, and William Mahone, a former Confederate general who was president of several railroads. Mahone was a major force in Virginia politics from around 1870 until 1883, when the Readjusters lost control to white Democrats.[4]

The Readjuster Party refinanced the Commonwealth's debts and invested in schools, especially for African Americans, who gained access to teaching jobs. The party increased funding for what is now Virginia Tech and established its black counterpart, Virginia State University. The Readjuster Party abolished the poll tax and the public whipping post. Because of expanded voting, Danville elected a black-majority town council and hired an unprecedented integrated police force.[5]

History

[edit]

Immediately after Virginia's adoption of a new state constitution and readmission into the United States in 1870, the first state legislature (a majority of whose members had never held political office before), after extensive lobbying, passed the Funding Act of 1871. This affirmed the state's pre-war debt by issuing bonds at 6% interest for 2/3 of the debt's face value at that same interest rate and promised to pay the remainder after agreement with West Virginia. Virginia's governor elected at that time, Gilbert Carlton Walker, was a banker in Norfolk and supported affirmation of the pre-war debt. He had the support of the Conservative Party formed by the Committee of Nine and characterized the issue as a "matter of honor." Confederate bonds were still worthless, and by this time prewar debt (exchanged after the law) had mostly been bought by out-of-state and even British investors at greatly discounted prices.[6]

In the decades before 1861, the Virginia Board of Public Works had invested in canals, roads, and railroads, by purchasing stock in and/or receiving mortgages on turnpike, toll bridge, canal and rail transportation companies. By 1861, those $34 million in investments with deferred 6% interest totaled about $46 million.[7] During the American Civil War, most of the railroads had been used for military purposes by armies on both sides, and had become strategic targets. Railroad lines were ripped up, terminals burned, bridges blown up and rolling stock destroyed. Several northwestern counties also seceded from Virginia to remain in the Union as the State of West Virginia. Much of what little railroad and canal infrastructure remained was in West Virginia.

Virginia needed its infrastructure rebuilt to restore its economic base, especially to get crops and manufactured goods to market. Accordingly, the Virginia General Assembly allowed reclassification of its first mortgages on existing rail lines to second mortgages, so that the railroads could get money from first mortgages to rebuild. Executive officials also allowed corporations to self-assess for other tax purposes, which meant corporate taxes were very low. However, the state still needed money to pay the debt as well as to operate the government and particularly public schools (theoretically possible since the days of Thomas Jefferson but only required by the state constitution since 1870). The Funding Act also contained a provision allowing coupons to be used at full value to pay taxes, which cut state revenues significantly (as the bonds were usually discounted significantly). In 1872, the General Assembly reduced the interest rate to 4%, but debt interest still constituted more than half of government expenditures, and the state ran a significant deficit. By the end of the decade, the state auditor was paying the bond debt, but not debts owed to teachers or to localities which had built public schools.

As much of the prewar debt was held by Northern banks and investors, the issue of debt repayment was complex. Those who supported a readjustment of the debt, were known as "Readjusters", whereas those in favor of funding the entire debt (plus interest), became known as "Funders".

The Readjuster Party promised to "readjust" the state debt, repeal the poll tax which had suppressed voting by blacks and poor whites, and increase funding for schools and other public facilities. Public education had been established for the first time under the Reconstruction-era legislature, but schools were underfunded, especially black schools. In 1878, Readjusters passed a law forbidding bond coupons to be used to pay state taxes, but Conservative John W. Daniel swore that he would rather have all public schools closed rather than divert money from bondholders, and Governor Frederick W.M. Holliday vetoed it. Harrison Riddleberger's law limiting bond interest to 3% was also vetoed. Before elections in the following year, the Conservatives passed a law and issued bonds (which still could be used to pay state taxes) with interest rates increasing each year, at 3% for the first ten years, then 4% for the next 20 years and 5% for their last decade.[7]

After the American Civil War, Mahone tried to combine many southern Virginia railroads into a system leading to the port of Norfolk, Virginia. However, the Atlantic, Mississippi and Ohio Railroad competed with the Chesapeake and Ohio Railroad (particularly in the northwestern part of the state) and went bankrupt in the Panic of 1873. That same financial crisis devastated Virginia, leading to large deficits as well as economic stagnation while wiping out the state's second mortgages and out-of-state interests were able to purchase the existing high interest 1871 bonds for pennies on the dollar.

While his railroad went through several receivers, Mahone ran for Governor, as the Conservative Party of Virginia (Democratic) candidate, but the little-known Holliday had defeated him in the primary. Mahone had shocked many fellow Conservatives by proposing to readjust the prewar debt.

Meanwhile, Rev. John E. Massey (Parson Massey) and Harrison H. Riddleberger, populists representing heavily taxed farmers in the state's Piedmont and northwestern regions, proposed to reorganize the state's debt at a lower interest rate.

Mahone became the Readjuster Party's driving force, as it held a convention in February 1879, and elected a majority of the Virginia General Assembly by year's end. He formed a coalition of Democrats and Republicans, with both white and black supporters.[8] He sought reduction in Virginia's pre-war debt, with an appropriate allocation to be borne by West Virginia. For several decades thereafter, the two states disputed West Virginia's share of the debt. The amount was finally settled in 1915 that West Virginia owed Virginia $12,393,929.50, based on negotiations over the interest amounts under a 1911 ruling by the United States Supreme Court that West Virginia was partially liable. The final installment was paid off in 1939.

Readjusters in power

[edit]

The Readjusters won a legislative majority in 1879 and again in 1881 (when Governor Holliday was not eligible for re-election). The Readjuster Party elected its candidate, William E. Cameron (former mayor of Petersburg) as governor, defeating John W. Daniel as the Conservative Party's candidate (and who ran on an anti-miscegenation platform as discussed later). Cameron served from 1882-1886. He caused more equal enforcement of the tax laws, which provided some relief to small businesses and farmers. Furthermore, many justices of the Virginia Supreme Court had terms expiring during the height of Readjuster power, so the Readjuster-dominated legislature elected Readjusters to replace them, as well as appointed former Confederate officer (and Taylor County, West Virginia legislator) George W. Hansbrough as the new reporter of judicial decisions.

In 1882, Riddleberger pushed a measure through the Virginia General Assembly reorganizing the prewar debt and repudiating about 1/3 of the prewar amount attributed to West Virginia, which Governor Cameron signed and the United States Supreme Court later upheld.[7] However, the bondholders continued to contest the decision, and also lobbied the Conservative Party of Virginia to affirm higher interest payments.

State legislators elected Mahone as a U.S. Senator, and he served one term, from 1881 to 1887. In Congress, he primarily aligned on voting with the members of the Republican Party, as did fellow Readjuster Harrison H. Riddleberger, whom fellow legislators elected to the U.S. Senate, where he served one term from 1883-1889.

Collapse

[edit]

While Republicans controlled the Presidency, Mahone controlled patronage in Virginia. When Democrat Grover Cleveland was elected U.S. President in 1884, patronage switched to what had been the Conservative Party (which became the Democratic Party in 1883).[citation needed]

The Readjusters lost control of the state legislature in 1883 after the Danville Massacre, which occurred immediately before voting began. Democrat Fitzhugh Lee became governor, defeating Readjuster John Sergeant Wise by 5% and succeeding Cameron in 1885. However, Readjuster Parson Massey won election as Lieutenant Governor in 1885. The collapse of the Readjuster party was also precipitated in part by its appointment of two freedmen to the Richmond school board.[citation needed] J. Taylor Ellyson, who would serve several terms as Richmond's mayor and later become Lieutenant Governor, was elected a state senator from Richmond on an anti-Readjuster platform.

Legislators elected Democrat John W. Daniel to succeed Mahone in 1886. John S. Barbour Jr., son of President of the Orange and Alexandria Railroad had organized revitalization of the Democratic Party on conservative principles in 1883, and succeeded Riddleberger in 1888. Virginia's Democratic legislature supported only Democratic candidates for the U.S. Senate, as Barbour and Thomas Staples Martin formed what would later become the Byrd Organization. Finally in 1892, the General Assembly adopted the Olcutt Act which forbade using the bond coupons to pay state taxes.

The collapse of the biracial Republican coalition was also related to a broader struggle over marriage, and the legislature's attempt to ban miscegenation. John M. Langston, whose father was white and mother of African and Native American heritage, ran for U.S. Congress in Mahone's Petersburg stronghold, criticizing the political boss for neglecting African Americans except on election day. Freedmen wanted to protect equality of rights in marriage, in part to gain protection for previous common-law marriages.[9]

Mahone stayed active in politics, but after losing his bid for reelection as U.S. Senator, in 1889 lost another bid for Governor as a Republican (losing by a much greater margin than had J. S. Wise four years earlier).[10] Riddleberger died in 1890, Mahone in 1895, and Parson Massey in 1901.

After the Readjuster Party disappeared, the Republican Party ceased to be competitive in the state. Virginia's Democratic Party dominated, and embedded Jim Crow laws in the Virginia Constitution of 1901/2. Some such laws had been adopted in the previous two decades (including forbidding those ever convicted of minor theft or an offense involving a whipping penalty to vote) and effectively disenfranchised most blacks and some poor whites. Legalized racial segregation of public facilities included all schools and transportation. Those with any African ancestry could not serve on juries or run for any office, and so lost any political voice. Most blacks were disenfranchised until after the mid-1960s, when the civil rights movement gained passage of federal legislation to enforce integration and voting rights.

Members

[edit]Federal officials

[edit]- William Mahone, U.S. Senator (1881–1887)

- Harrison H. Riddleberger, U.S. Senator (1883–1889)

- John Critcher, U.S. Representative (1871–1873)

- John Ambler Smith, U.S. Representative (1873–1875)

- John Paul, U.S. Representative (1881–1883)

- Abram Fulkerson, U.S. Representative (1881–1883)

- Robert Murphy Mayo, U.S. Representative (1883–1884)

- Harry Libbey, U.S. Representative (1883–1887)

- Benjamin S. Hooper, U.S. Representative (1883–1885)

- Henry Bowen, U.S. Representative (1883–1885, 1887–1889)

- John Sergeant Wise, U.S. Representative (1883–1885)

State officials

[edit]- William E. Cameron, Governor of Virginia (1882–1886)

- John F. Lewis, Lieutenant Governor of Virginia (1869–1870, 1882–1886)

- John E. Massey, Lieutenant Governor of Virginia (1886–1890)

- Frank S. Blair, Attorney General of Virginia (1882–1886)

- Benjamin W. Lacy, Justice of the Supreme Court of Virginia (1883–1895)

- Daniel M. Norton, Virginia State Senator (1871–1873, 1877–1887)

- Robert Norton, Virginia State Delegate (1869–1874, 1876–1883)

- Edward David Bland, Virginia State Delegate (1879–1884)

- Amos Andre Dodson, Virginia State Delegate (1883–1885)

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Pearson, C. C. (July 1916). "The Readjuster Movement in Virginia". The American Historical Review. 21 (4): 734–749. doi:10.2307/1835892. hdl:2027/coo1.ark:/13960/t08w3zv24. JSTOR 1835892.

- ^ "Readjuster Party, The – Encyclopedia Virginia".

- ^ Pearson, Charles Chilton (1917). The Readjuster Movement in Virginia. Yale University Press. p. 146.

- ^ "Readjuster Party". Encyclopedia Virginia. Retrieved March 4, 2015.

- ^ "William Mahone". Lva.virginia.gov. Retrieved November 27, 2010.

- ^ Moger, Allen (1968). Virginia: Bourbonism to Byrd, 1870-1925. University Press of Virginia. OCLC 435376

- ^ a b c "Readjuster Party, The". www.encyclopediavirginia.org. Retrieved August 23, 2017.

- ^ Dailey, Jane (2000). Before Jim Crow: The Politics of Race in Postemancipation Virginia. Chapel Hill, NC: The University of North Carolina Press. p. 40.

- ^ Dailey, Jane Elizabeth; Glenda Elizabeth Gilmore; Bryant Simon (2000). Jumpin' Jim Crow. Princeton University Press. pp. 90–104. ISBN 0-691-00193-6.

- ^ Tarter, Brent (2016). A Saga of the New South: Race, Law, and Public Debt in Virginia. Charlottesville, VA: University of Virginia Press. ISBN 9780813938769. OCLC 950985518.