Chew Stoke

| Chew Stoke | |

|---|---|

| Village and civil parish | |

A view of Chew Stoke | |

Parish map | |

Location within Somerset | |

| Area | 3.1 sq mi (8.0 km2) |

| Population | 1,038 (2021) |

| • Density | 335/sq mi (129/km2) |

| OS grid reference | ST555615 |

| • London | 111 mi (179 km) E |

| Civil parish |

|

| Unitary authority | |

| Ceremonial county | |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Settlements |

|

| Post town | BRISTOL |

| Postcode district | BS40 |

| Dialling code | 01275 |

| Police | Avon and Somerset |

| Fire | Avon |

| Ambulance | South Western |

| UK Parliament | |

| Website | www |

Chew Stoke is a small village and civil parish in the affluent Chew Valley, in Somerset, England, about 8 miles (13 km) south of Bristol and 10 miles north of Wells. It is at the northern edge of the Mendip Hills, a region designated by the United Kingdom as an Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty, and is within the Bristol and Bath green belt. The parish includes the hamlet of Breach Hill, which is approximately 2 miles (3.2 km) southwest of Chew Stoke itself.

Chew Stoke has a long history, as shown by the number and range of its heritage-listed buildings. The village is at the northern end of Chew Valley Lake, which was created in the 1950s, close to a dam, pumping station, sailing club, and fishing lodge. A tributary of the River Chew, which rises in Strode, runs through the village.

The population of 1,038 is served by one shop, one working public house, a primary school and a bowling club. Together with Chew Magna, it forms the ward of Chew Valley North in the unitary authority of Bath and North East Somerset. Chew Valley School and its associated leisure centre are less than a mile (1.6 km) from Chew Stoke. The village has some areas of light industry but is largely agricultural; many residents commute to nearby cities for employment.

History

[edit]Prehistory

[edit]Archaeological excavations carried out between 1953 and 1955 by Philip Rahtz and Ernest Greenfield from the Ministry of Works found evidence of extensive human occupation of the area. Consecutive habitation, spanning thousands of years from the Upper Palaeolithic, Mesolithic, and Neolithic periods[1] (Old, Middle, and New Stone Age), to the Bronze and Iron Ages had left numerous artefacts behind. Discoveries have included stone knives, flint blades, and the head of a mace, along with buildings and graves.[1]

Romano-Celtic temple

[edit]Chew Stoke is the site of a Romano-Celtic double-octagonal temple, possibly dedicated to the god Mercury. The temple, on Pagans Hill, was excavated by Philip Rahtz between 1949 and 1951. It consisted of an inner wall, which formed the sanctuary, surrounded by an outer wall forming an ambulatory, or covered walkway 56.5 feet (17.2 m) across. It was first built in the late 3rd century but was twice rebuilt, finally collapsing in the 5th century.[2] The positioning of the temple on what is now known as Pagans Hill may seem apt, but there is no evidence for any link between the existence of the temple and the naming of the road.[3]

Middle Ages

[edit]During the Middle Ages, farming was the most important activity in the area, and farming, both arable and dairy, continues today. There were also orchards producing fruits such as apples, pears, and plums.[1] Evidence exists of lime kilns, used in the production of mortar for the construction of local churches.[1]

In the Domesday Book of 1086, Chew Stoke was listed as Chiwestoche, and was recorded as belonging to Gilbert fitz Turold. He conspired with Robert Curthose, the Duke of Normandy, against King William Rufus, and subsequently all his lands were seized. The next recorded owner was Lord Beauchamp of Hache. He became "lord of the manor" when the earls of Gloucester, with hereditary rights to Chew Stoke, surrendered them to him.[4] According to Stephen Robinson, the author of Somerset Place Names, the village was then known as Chew Millitus, suggesting that it may have had some military potential. The name "Stoke", from the old English stoc, meaning a stockade, may support that idea.[5]

The parish was part of the hundred of Chew.[6]

Bilbie family of bell and clockmakers

[edit]

The Bilbie family of bell founders and clockmakers lived and worked in Chew Stoke for more than 200 years, from the late 17th century until the 19th century. They produced more than 1,350 church bells, which were hung in churches all over the West Country. Their oldest surviving bell, cast in 1698, is still giving good service in the local St Andrew's Church. The earliest Bilbie clocks date from 1724 and are highly prized. They are mostly longcase clocks, the cheapest with 30-hour movements in modest oak cases, but some have high quality eight-day movements with additional features, such as showing the high tide at Bristol docks. These latter clocks were fitted into quality cabinet maker cases and command high prices.[7][8]

Recent history

[edit]In the 20th century, Chew Stoke expanded slightly with the influx of residents from the Chew Valley Lake area. These new residents were moved to Chew Stoke when the lake was created in the 1950s.[1] In World War II, 42 children and three teachers, who had been evacuated from Avenmore school in London, were accommodated in the village.[4] On 10 July 1968, torrential rainfall, with 175 millimetres (7 in) falling in 18 hours on Chew Stoke, double the area's average rainfall for the whole of July,[9] led to widespread flooding in the Chew Valley, and water reached the first floor of many buildings.[4] The damage in Chew Stoke was not as severe as in some of the surrounding villages, such as Pensford; however, fears that the Chew Valley Lake dam would be breached caused considerable anxiety.[9][10]

On 4 February 2001, Princess Anne opened the Rural Housing Trust development at Salway Close. Each year, over a weekend in September (usually the first), a "Harvest Home" is held with horse and pet shows, bands, a funfair, and other entertainments. The Harvest Home was cancelled in 1997 as a mark of respect following the death of Princess Diana in the previous week. The Radford's factory site, where refrigeration equipment was formerly manufactured, was identified as a brownfield site suitable for residential development in the 2002 Draft Local Plan of Bath and North East Somerset.[11] That plan has generated controversy about balancing land use to meet residential, social, and employment needs.[12]

During November 2012 a series of floods affected many parts of Britain. On 22 November a man died after his car was washed down a flooded brook in Chew Stoke and trapped against a small bridge.[13][14]

Governance

[edit]

Chew Stoke has its own nine-member parish council with responsibility for local issues, including setting an annual precept (local rate) to cover the council's operating costs and producing annual accounts for public scrutiny. The parish council evaluates local planning applications and works with the local police, district council officers, and neighbourhood watch groups on matters of crime, security, and traffic. The council's role also includes initiating projects for the maintenance and repair of parish facilities, as well as consulting with the district council on the maintenance, repair, and improvement of highways, drainage, footpaths, public transport, and street cleaning. Conservation matters (including trees and listed buildings) and environmental issues are also the responsibility of the council.

The village is part of the ward of Chew Valley in the unitary authority of Bath and North East Somerset, which has the wider responsibility for providing services such as education, refuse collection, and tourism. The ward is currently represented by Councillors Anna Box and David Harding, members of the Liberal Democrats.[15] It is also part of the North East Somerset and Hanham, and was part of the South West England constituency of the European Parliament prior to Britain leaving the European Union in January 2020.

The police service is provided by Avon and Somerset Constabulary with two Community Support Officer and one police officer covering the wider Chew Valley area. The Avon Fire and Rescue Service have a fire station at Chew Magna.

Geography

[edit]The area of Chew Stoke is surrounded by arable land and dairy farms on the floor of the Chew Valley. It is located along the Strode Brook tributary of the River Chew, on the northwest side of the Chew Valley Lake. While much of the area has been cleared for farming, trees line the tributary and many of the roads. The village is built along the main thoroughfare, Bristol Road, which runs northeast to southwest. An older centre is located along Pilgrims Way, which loops onto Bristol Road and features an old stone packhorse bridge—now pedestrianised—and a 1950s Irish bridge, used as a ford in winter.[4] The bridge is 7 feet 6 inches (2.29 m) wide and has 36 inches (910 mm) parapets.[16] Houses line both of these roads, with residential cul-de-sacs and lanes extending from them.

Chew Stoke is approximately 8 miles (13 km) south of Bristol, 10 miles (16 km) north of Wells, 15 miles (24 km) west of Bath, 17 miles (27 km) east of Weston-super-Mare, and 9 miles (14 km) southwest of Keynsham. It is 1.3 miles (2.1 km) south of Chew Magna on the B3130 road that joins the A37 and A38. The A368 crosses the valley west of the lake. The "Chew Valley Explorer" bus route 672/674, running from Bristol Bus Station to Cheddar, provides public transport access. This service is operated by CT coaches and Eurotaxis and subsidised by Bath and North East Somerset council.[17] In 2002, a 1.9-mile (3.1 km) cycle route, the Chew Lake West Green Route, was opened around the western part of the lake from Chew Stoke. It forms part of the Padstow to Bristol West Country Way, National Cycle Network Route 3. It has all-weather surfacing, providing a smooth off-road facility for ramblers, mobility-challenged visitors, and cyclists of all abilities. Funding was provided by Bath and North East Somerset Council, with the support of Sustrans and the Chew Valley Recreational Trail Association. The minor roads around the lake are also frequently used by cyclists. Bristol Airport is approximately 10 miles (16 km) away, and the nearest train stations are Keynsham, Bath Spa, and Bristol Temple Meads.

Demography

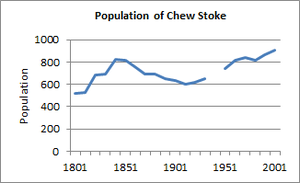

[edit]The population of Chew Stoke, according to the census of 1801, was 517. This number increased slowly during the 19th century to a maximum of 819 but fell to around 600 by the end of the century. The population remained fairly stable until World War II. During the latter half of the 20th century, the population of the village rose to 905 people. Data for 1801–1971 is available at Britain Through Time;[18] data for 1971–2001 is available from BANES(2011 Census)[19] The 2001 Census gives detailed information about the Chew Valley North ward, which includes both Chew Magna and Chew Stoke. The ward had 2,307 residents, living in 911 households, with an average age of 42.3 years. Of those, 77% of residents described their health as 'good', 21% of 16- to 74-year-olds had no work qualifications, and the area had an unemployment rate of 1.3%. In the Index of Multiple Deprivation 2004, the ward was ranked at 26,243 out of 32,482 wards in England, where 1 was the most deprived and 32,482 the least deprived.[20] A small number of light industrial/craft premises exist at "Fairseat Workshops", formerly the site of a dairy. However, they provide little employment, and many residents commute to jobs in nearby cities.[4] The population has increased since; in the 2011 census there were 991 residents recorded,[21] and 1,038 in the 2021 census.[22]

Landmarks

[edit]

St Andrew's Church

[edit]St Andrew's Church, a Grade II* listed building on the outskirts of Chew Stoke, was constructed in the 15th century and underwent extensive renovation in 1862.[23][24] The inside of the church is decorated with 156 angels in wood and stone,[4] and the church includes a tower with an unusual spirelet on the staircase turret. In the tower hang bells cast by the Bilbie family.[24] The reconstructed Moreton Cross in the churchyard was moved there when Chew Valley Lake was flooded,[1] and the base of the cross shaft, about 80 feet (24 m) southwest of the tower, is thought to date from the 14th century and is itself a Grade II* listed building,[25] as is the Webb monument in the churchyard.[26] The churchyard gate, at the southeast entrance, bears a lamp provided by public subscription to commemorate Queen Victoria's Jubilee of 1897 and is a Grade II listed structure.[27]

In the church are bronze plaques commemorating the eleven local people who died in World War I and the six who were killed in World War II.[28] There is also a stained glass window showing a saint with a sword standing on a snake, and crossed flags commemorating those from World War II.[29] There is also a memorial plaque to the local Bilbie family of bell founders and clockmakers inside the church, and just inside the porch, on the left of the church door, is a stone figure holding an anchor, which was moved to the church from Walley Court with the flooding of the lake. There is an unconfirmed story that this was given to the Gilbert family, then living at the court, by Queen Elizabeth I.[30]

Rectory

[edit]

The Rectory, at the end of Church Lane, opposite the church hall, is believed to have been built in 1529 by Sir John Barry, rector 1524–46. It has since undergone substantial renovations, including the addition of a clock tower for the Rev. W.P. Wait and further alterations c.1876 for Rev. J. Ellershaw. The clock tower has since been removed. The building has an ornate south front with carvings of shields bearing the coat of arms of the St Loe family, who were once chief landowners in the area, alone or impaled with arms of Fitzpane, Ancell, de la Rivere, and Malet. It is Grade II* listed.[31]

New rectory

[edit]

The Reverend John Ellershaw built the new rectory in the 1870s. The last rector to occupy it was Lionel St Clair Waldy from 1907 to 1945. It was then bought by Douglas Wills, who donated it and the rectory field to Winford Hospital as a convalescent home for 16 children. It was later used as a nurses' home before being sold for private use.[4] It is now split into several residential units.[32]

Grade II listed buildings

[edit]As with many cities and towns in the United Kingdom, the age of a number of the buildings in Chew Stoke, including the church, school, and several houses, reflects the long history of the village. For example, Chew Stoke School has approximately 170 pupils between 4 and 11 years old. After the age of 11, most pupils either attend Chew Valley School or any of the independent schools in the area. These two buildings were built in 1858 on the site of a former charity school founded in 1718. The architect was S.B. Gabriel of Bristol. Additional classrooms were built in 1926, and further alterations and extensions were carried out in 1970.[33]

An obelisk on Breach Hill Lane, dating from the early-to-mid-19th century, is said to have been built as a waterworks marker. It has a square limestone plinth about 3 feet (1 m) high. The obelisk is about 32 feet (10 m) high with a pyramidal top and small opening at the top on two sides.[34]

The importance of farming is reflected in the age of many of the farmhouses. Manor Farm, on Scot Lane (not to be confused with at least two other Manor Farms in the locality) is thought to date from 1495 and, as such, is probably the oldest building in the village. Presently (2007) occupied by Mr and Mrs Slater; the building has recently (2002) undergone a sympathetic extension to incorporate an old semi-derelict barn onto the main house for use as a garage and workshop. Mr Slater, a Chartered Engineer, is interested in bringing the art of clock making back to the village. Rookery Farmhouse, in Breach Hill Lane, is dated at 1720, with later 18th century additions to either side of the central rear wing.[35] An attached stable, 20 feet (6 m) northeast of the farmhouse, is also a Grade II listed building.[36] School Farmhouse, in School Lane, dates from the late 17th century and has a studded oak door in the side of the house.[4][37] Wallis Farmhouse, farther along School Lane, is dated at 1782.[38] Yew Tree Farmhouse, one of the oldest buildings in the area, is a cruck built farmhouse of which there are very few in North Somerset. It was included in the dendrochronology project carried out by the Somerset Vernacular Building Research Group 1996–1998 and the crucks gave a felling date of 1386, the house has been extensively altered and added to over later centuries.[39] North Hill Farmhouse also has 15th century origins.[4][40] Paganshill Farmhouse dates from the 17th century.[41] Fairseat Farmhouse is from the 18th century and includes a plaque recording that John Wesley preached at the house on 10 September 1790. In August of that year, Fairseat Farmhouse was "registered among the records of this County as a House set apart for the worship of God and religious exercise for Protestant Dissenters." At that time the house belonged to Anna Maria Griffon. In the garden is a large evergreen oak (Ilex) which measured 98 feet (30 m) across until half of it broke away in a gale in 1976.[4][42]

The Methodist Chapel was built in 1815/16 after religious services had been established at Fairseat Farm, and the chapel was rebuilt in the late 19th century with limestone walls with stone dressings and a slate hipped roof with brick eaves stacks and crestings.[4][43]

In the hamlet of Stoke Villice, which is south of the main village, there is a 19th-century milestone inscribed "8 miles to Bristol" that also has listed status.[44]

Education

[edit]Chew Stoke Church of England Voluntary Aided Primary School serves the village itself and surrounding villages in the Chew Valley. It is a Church of England voluntary controlled school linked with the St. Andrew's parish church. It has about 170 pupils between 4 and 11 years old. After the age of 11, most pupils attend Chew Valley School.[45]

The school was founded as a charity in 1718 making it one of the oldest schools in Somerset. Its original buildings were demolished in 1858 and replaced with new ones to designs by S.B. Gabriel that are now Grade II listed. The school bell was donated by the Bilbie family of bell founders based in the village. Additional classrooms were built in 1926, and further alterations and extensions were built in 1970, 1995 and 2001.[33]

In July 2018, the school celebrated its 300th birthday making it one of the oldest state schools in England. A service was held at St Andrew's Church led by the Bishop of Taunton – The Right Reverend Ruth Worsley, and was followed by a tea party at the school, and the planting of a time capsule.[46]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f Ross, Lesley, ed. (2004). Before the Lake: Memories of the Chew Valley. The Harptree Historic Society. ISBN 0-9548832-0-9.

- ^ Aston, Michael; Rob Iles (1987). The archeology of Avon. Bristol: Avon County Council. ISBN 978-0-86063-282-5.

- ^ Dunning, Robert (1983). A History of Somerset. Chichester: Phillimore & Co. ISBN 0-85033-461-6.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Hucker, Ernest (1997). Chew Stoke Recalled in Old Photographs. Ernest Hucker. ISBN 0-9531700-0-4.

- ^ Robinson, Stephen (1992). Somerset Place Names. Wimborne, Dorset: The Dovecote Press Ltd. ISBN 978-1-874336-03-7.

- ^ "Somerset Hundreds". GENUKI. Archived from the original on 5 May 2019. Retrieved 8 October 2011.

- ^ "Bilbie – Bell founders and clockmakers". Troyte Ringing Centre. Archived from the original on 30 September 2007. Retrieved 5 November 2006.

- ^ Moore, J.; Rice R. & Hucker, E. (1995). Bilbie and the Chew Valley clockmakers : the story of the renowned family of Somerset bellfounder-clockmakers /Clockmakers. The authors. ISBN 0-9526702-0-8.

- ^ a b Richley, Rob (June 2008). The Chew Valley floods of 1968. Exeter: Environment Agency.

- ^ "Memories of Bristol's Weather – The Great Flood of 1968". bristolhistory.com. Archived from the original on 4 August 2007. Retrieved 3 July 2007.

- ^ "Bath & North East Somerset Local Plan Deposit Draft January 2002". Bath & North East Somerset Council. Archived from the original on 27 September 2006. Retrieved 5 November 2006.

- ^ "Plans for Radfords site to be unveiled". Chew Valley Gazette. Archived from the original on 7 February 2012. Retrieved 3 July 2007.

- ^ "Man dies as torrential rain and wind cause UK flood havoc". BBC News. 23 November 2012. Archived from the original on 23 November 2012. Retrieved 23 November 2012.

- ^ "Police preserve the scene after man dies in Somerset". ITV. Archived from the original on 23 November 2012. Retrieved 23 November 2012.

- ^ "Your Councillors by Ward". Bath and North East Somerset Council. Retrieved 11 August 2024.

- ^ Hinchliffe, Ernest (1994). Guide to the Packhorse Bridges of England. Cicerone. p. 136. ISBN 978-1852841430.

- ^ Harding, J. "Changes to Chew Valley Explorer". Bristol Evening Post. Archived from the original on 14 January 2013. Retrieved 17 September 2010.

- ^ "Chew Stoke Somerset through time : Population Statistics : Total Population". A Vision of Britain through Time. Archived from the original on 3 November 2012. Retrieved 6 December 2007.

- ^ "Chew Stoke Parish". Neighbourhood Statistics. Office for National Statistics. Archived from the original on 1 January 2014. Retrieved 31 December 2013.

- ^ "Neighbourhood Statistics LSOA Bath and North East Somerset 021A Chew Valley North". Office for National Statistics 2001 Census. Archived from the original on 25 May 2011. Retrieved 25 April 2006.

- ^ UK Census (2011). "Local Area Report – Chew Stoke parish (E04000958)". Nomis. Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 26 January 2024.

- ^ UK Census (2021). "2021 Census Area Profile – Chew Stoke parish (E04000958)". Nomis. Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 26 January 2024.

- ^ Historic England. "Church of St. Andrew (1129632)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 9 May 2006.

- ^ a b Pevsner, Nikolaus (1958). The Buildings of England: North Somerset and Bristol. Penguin Books. ISBN 0-300-09640-2.

- ^ Historic England. "base of cross shaft (1136107)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 9 May 2006.

- ^ Historic England. "Webb monument (1129633)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 9 May 2006.

- ^ Historic England. "overthrow and gates (1320748)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 9 May 2006.

- ^ "Chew Stoke WWI Ref: 7488". United Kingdom National Inventory of War Memorials. Archived from the original on 20 October 2021. Retrieved 13 September 2015.

- ^ "Chew Stoke WWII Ref: 7489". United Kingdom National Inventory of War Memorials. Archived from the original on 20 October 2021. Retrieved 13 September 2015.

- ^ Mason, Edmund J.; Mason, Doreen (1982). Avon Villages. Robert Hale Ltd. ISBN 0-7091-9585-0.

- ^ Historic England. "The Rectory (1320747)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 9 May 2006.

- ^ Historic England. "Old Rectory (1129631)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 9 May 2006.

- ^ a b Historic England. "Chew Stoke School (1320749)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 9 May 2006.

- ^ Historic England. "Obelisk, Breach Hill Lane (1320746)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 9 May 2006.

- ^ Historic England. "Rookery Farmhouse (1129671)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 9 May 2006.

- ^ Historic England. "Stable (1320725)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 9 May 2006.

- ^ Historic England. "School Farmhouse (1129635)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 9 May 2006.

- ^ Historic England. "Wallis Farmhouse (1136118)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 9 May 2006.

- ^ Historic England. "Yew Tree Farmhouse (1136115)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 9 May 2006.

- ^ Historic England. "North Hill Farmhouse (1136056)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 9 May 2006.

- ^ Historic England. "Paganshill Farmhouse (1129628)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 9 May 2006.

- ^ Historic England. "Fairseat Farmhouse (1320750)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 9 May 2006.

- ^ Historic England. "Methodist Chapel (1129630)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 9 May 2006.

- ^ Historic England. "Milestone (1136062)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 9 May 2006.

- ^ "Chew Stoke Church Primary School". Chew Stoke Primary School. Archived from the original on 1 May 2006. Retrieved 25 April 2006.

- ^ "Service to mark Chew Stoke Church School's 300th birthday. - Diocese of Bath and Wells". Archived from the original on 27 October 2020. Retrieved 24 October 2020.

Bibliography

[edit]- Durham, I. & M. (1991). Chew Magna and the Chew Valley in old photographs. Redcliffe Press. ISBN 1-872971-61-X.

- Janes, Rowland, ed. (1987). The Natural History of the Chew Valley. Biografix. ISBN 0-9545125-2-9.

- Hucker, E (1997). Chew Stoke recalled in old photographs. S.l.: E. Hucker. ISBN 978-0-9531700-0-5.